How to farm rare breeds commercially and get a premium

Rare breeds will always be unable to compete against modern, commercial animals when it comes to productivity.

However, with the potential for lower production costs and the opportunity to supply niche markets at a premium, farmers are finding ways to use these breeds for commercial purposes.

A self-confessed newcomer to farming, David Fenton has built up a respectable business with a herd of original population organic Hereford cattle.

“I started out 30 years ago with a small amount of land for livestock and bought some modern Hereford cattle – bred from North American imports – which in hindsight probably contained non-Hereford genetics.

“I saw a lot of inconsistency within the breed so did some more research and found that there was an original population.”

Traditional Herefords are shorter-legged and thicker set than modern types, with a fantastic ability to convert grass into high-quality meat – making them a good option for extensive suckler systems.

See also: Endangered beef breed making a comeback

With 280ha of grassland at Honour Farm, near Tenterden, Kent, Mr Fenton now has 110 of the 2,500 original population cows in the UK.

The cows graze 210 days a year on average – fed only on grass – with conserved silage or hay in the winter.

Steers are finished at two years old to keep costs down, says Mr Fenton. “To finish a cow quickly, you have to use a lot of inputs, but the Herefords finish very well just on grass.”

The market for meat and stock

When it came to sourcing a market for the beef, the margins of selling into the commercial trade didn’t stack up, so Mr Fenton set up a farm shop and butchery in 2003, through which he sells between 50 and 60 steers a year at a premium price.

“The meat is hung for 28 days, and is well-marbled and tender – customers regularly comment on the good quality and will pay more for it.”

The farm also generates income through the sale of quality, pedigree breeding stock.

“We keep back six to eight males that are good enough for breeding and the rest are sold as steers. We use five stock bulls and try to use homebred whenever we can. Females that aren’t kept for breeding are sold on as pedigree breeding heifers.”

Despite being a rare breed, culling when necessary is vital, says Mr Fenton. “We cull if a cow has severe lameness, a health problem or a trait we don’t like – it is absolutely essential to do so to retain maximum quality.”

Fertility is another strong trait of the breed – with only six cows slipping from the spring to autumn block this year.

“Easy calving is very important – I’ve only had to assist with one birth this year. They produce pretty good calves – robust and quick to get going.”

Looking into the numbers

Average calf weight is 35kg, with a daily liveweight gain of 0.7kg/day – taking them to 450-500kg at finishing. “Calves receive no creep feed and grow beautifully,” says Mr Fenton.

“We are about to move on to weighing at birth, 200 days and 400 days, which will give us an even better insight into the calf performance.”

In terms of profitability, rearing a steer from calving to finishing is estimated to cost the farm £1,695, based on 2016-17 figures. The average return is £2,100, though this is often much more, explains Mr Fenton.

“Income from meat sales is about £95,000/year. With the additional £30,000 from pedigree sales, this takes our total income to £125,000 – leaving us with a £48,000 margin for the operation.”

For Mr Fenton, keeping production simple is key. “Conventional breeds are bigger to compete in the markets but this puts pressure on farmers to feed them large amounts just for maintenance and as a result provide more space – it changes the nature of both farming and the animal.”

Tamworth Pigs

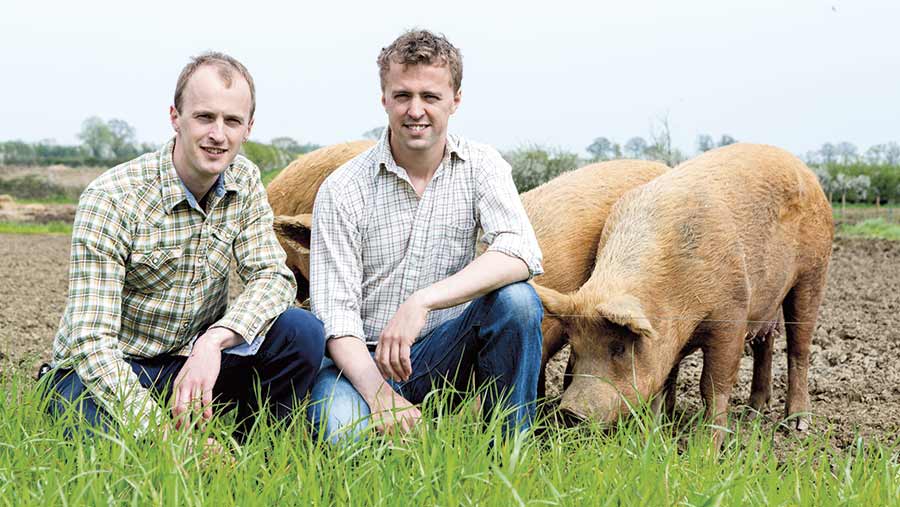

Jon and Nick Francis are supplying pork to Michelin-star restaurants across the UK.

Farming 24ha in Oxfordshire, the first-generation farmers are running an 80-sow herd of Tamworth pigs commercially.

“My brother, Jon, and I started out eight years ago with just two sows,” explains Nick. “We are not from a farming background but are food lovers and we wanted to be able to produce high-quality meat.”

As there are no stock buildings on the farm, Mr Francis chose Tamworths as he needed a breed that could survive outside.

“Tamworths are very hardy. We rear them completely outdoors and they produce great pork with good fat cover.”

Despite high production costs – with each animal needing to return £310 to cover costs – Mr Francis found a niche market, supplying to high-end, independent restaurants for a premium value.

“We also had the opportunity to create our own retail space and so about 30% of our pork is sold through our butcher’s shop.”

At a glance

- Finishing: 175 days or 200 days for larger processing pigs

- Carcass weight: 65kg (pork pigs) or 75-80kg (processing pigs)

- Growth rate: 400g/day from weaning to slaughter

- Feeding: Grower ration until 12 weeks (19% protein, 1.1% lysine), followed by finisher ration (15% protein, 0.8% lysine)

- Breeding: Natural service

- Key traits: Good level of intramuscular fat, hardy, high-quality meat

Gloucester cattle

Clifford Freeman owns 25% of the UK’s Gloucester cattle.

His family involvement with Gloucester cattle dates back to 1971, when his father purchased his first two cattle.

“I have been involved since I was about six, and when I took the stock on from my father I began to collect any of the Gloucester breed I could find,” he explains. “Today, I have 270 cows plus followers.

The cattle are slow to finish – at about 34 months – which can be an issue for cashflow.

However, with a hotel and restaurant in the Isles of Scilly, Mr Freeman can supply the kitchens directly, as well as selling the meat at a premium locally and some going into commercial trade – having found outlets that are prepared to slaughter beef over 30 months.

“We can sell the carcass at a premium and the rest at a commercial rate,” he explains. “The benefit of selling locally is that more and more people are becoming concerned where their food comes from; we are very keen on traceability.”

Despite farming a protected breed, Mr Freeman believes in a strict culling policy to preserve the best traits of the breed.

“There is no point in keeping an animal if it doesn’t stack up for commercial use. When keeping these rare breeds, it needs to be done as commercially as possible.”

At a glance

- Finishing: 34 months

- Carcass weight: 300-370kg

- Growth rate: Don’t weigh

- Feeding: Grass-based, grazing April-November with silage or hay in the winter. Calves reared only on milk and grass

- Breeding: Seven stock bulls, using homebred when possible

- Key traits: Good forage converters, level lactation therefore good sucklers, easy calving, good back end