Exclusive: Farmers Weekly spends a night on the badger cull

Badger culling is under way for a sixth consecutive year in England and the policy has been widened to 11 new areas, bringing the total to 43. Up to 63,000 badgers could be shot this season in an effort to protect cattle from contracting TB.

While farmers insist the policy is helping tackle the disease, farmer-led culling groups have been advised to keep their operations secret amid threats of violence and intimidation from anti-cull activists, who have slammed the badger cull as a “shot in the dark” for the government.

In a media first, Farmers Weekly had exclusive access to a patrol as an observer, joining farmers in the South West.

See also: 5 ways to improve TB control in the UK

Cull operation

A bright, orange sunset illuminates the night sky as I meet the first farmer, who is also a trained marksman. We drive five minutes to the home of a second farmer, who acts as a local cull administrator.

After we arrive, the administrator outlines the role in the culling operation. Badger sett surveys are carried out each year in January/February and the aim is to reduce the local badger population to about 1/sq km.

There are 20 marksmen operating within this cull zone alongside “spotters” who accompany marksmen and use infrared cameras to help identify badgers on the ground. Inside the zone, there is a 50/50 split of cage trapping and shooting and “free shooting” of roaming badgers.

Peanuts buried in the ground and covered by a stone are used as bait, both for trapping and free-shooting. A badger will dig for the peanuts, which signals its presence if it does not take the bait in the trap.

After the badgers are shot, their carcasses are bagged, tagged and transported to a central collection point to be incinerated.

TB devastation

Next, we visit the nearby home of a third farmer, a dairy farmer who is also a spotter. He tells me his business has been ravaged by TB. “Bovine TB is a terrible disease. It’s all you think about it 24/7,” he says, his voice cracking with emotion.

For 15 years, his closed dairy herd had been under TB restrictions on and off, with dozens of cows condemned to slaughter, causing huge emotional and financial strain.

Latest bovine TB statistics for England

- 7.7 million total cattle tests

- -3.3% year-on-year fall in new TB herd incidents

- -7% year-on-year fall in new TB herd incidents in High Risk Area

- 13% year-on-year increase in new TB herd incidents in Edge Area

- 5.7% of herds not officially TB-free

- 32,413 TB-infected cattle slaughtered

Source: Defra (during 12 months to end of June 2019)

However, for the past 18 months, his herd has gone clear – and he believes that lowering the disease reservoir in wildlife is the reason.

“That’s what drives people to do this. We don’t do this for fun,” he says. “The big thing is losing good cows. That’s what kills people.

“When you have got a really nice cow that you’ve reared and she’s come to her second lactation and she’s full of milk and looks a picture, then she goes down – and that kills you.

“Then you have got to deal with it. You have got to keep her until they pick her up and then you’ve got to lead her on that lorry.”

Crippling costs

According to Defra, the average cost of a bovine TB breakdown on a farm is £34,000, of which roughly £14,000 falls to the farmer, through loss of animals, labour costs and business disruption to movements incomes.

Dairy farmers who have milk contracts to fulfil must also factor in the risks of buying in new cows that may also be TB-infected. Before they started culling badgers here, 90 out of 400 herds were under TB restrictions.

The dairy farmer is one of 300 farmers across the zone who have signed up to allow trained marksmen to shoot badgers across their land. Now, about 30 of the 400 farms are under TB restrictions.

Training to become a spotter involves learning to distinguish between badgers and other animal silhouettes – including hares, foxes and deer – through a thermal imaging camera.

Operations centre

The marksman and spotter signal it’s time to leave. The marksman calls a national operations centre to notify them that they are “going live”. While we drive a short distance to the first farm, the marksmen explains that, to shoot badgers lawfully, they must be properly trained and vetted.

Each person must undergo theory and practical training to demonstrate competency in the use and safe handling of firearms. Marksmen are trained to shoot badgers cleanly in the trunk of the body, near the heart/lung area to offer greater chances of an instant kill.

Independent analysis in the first year of the culls found that up to 23% of badgers take more than five minutes to die after they have been shot. It is a figure which has caused outrage among animal welfare groups. But in this marksman’s experience, shot badgers die instantly.

“You have to shoot where you are comfortable. I tend to shoot up to 150 feet. I have never missed a badger,” he says. “For my training, I had to shoot three bullets within a 10p piece at 100m while resting on a straw bale.”

We get out of the 4×4 and the spotter uses the camera to scan hedges and field boundaries for badgers. Suddenly, he spots a deer by a hedge, but there are no signs of any badgers. We jump back in the car and drive to different fields. The farmers use gates as vantage points to scan the horizon.

If they do spot badgers, they say leaning on gates can help marksmen to steady the rifle.

Badger foraging

Next, we drive to an arable farm. The marksman explains that badgers sometimes leave their setts and wander into the middle of fields to forage for grubs, especially slugs and worms.

Badgers are nocturnal. But the farmers say the clear night may be discouraging them from leaving their setts. When there is a bright moon, they tend to come out later, they explain.

On warm, damp nights, badgers are more likely to emerge from their setts as more worms come to the surface to breed, they add. The farmers say patience is required to spot badgers on farmland. But after almost three hours of searching, they decide to call it a day. They plan to return in the next 48 hours.

“None of us wanted to do this, but we all feel it’s necessary and we are prepared to stick our necks out and get it done very effectively,” says the marksman, after we arrive back at the meeting point.

“That’s why I get steamy when people criticise us for what we are doing because it’s the only show in town. No one has got any ideas of how to get rid of the disease any other way, apart from vaccination, which has no basis in science.”

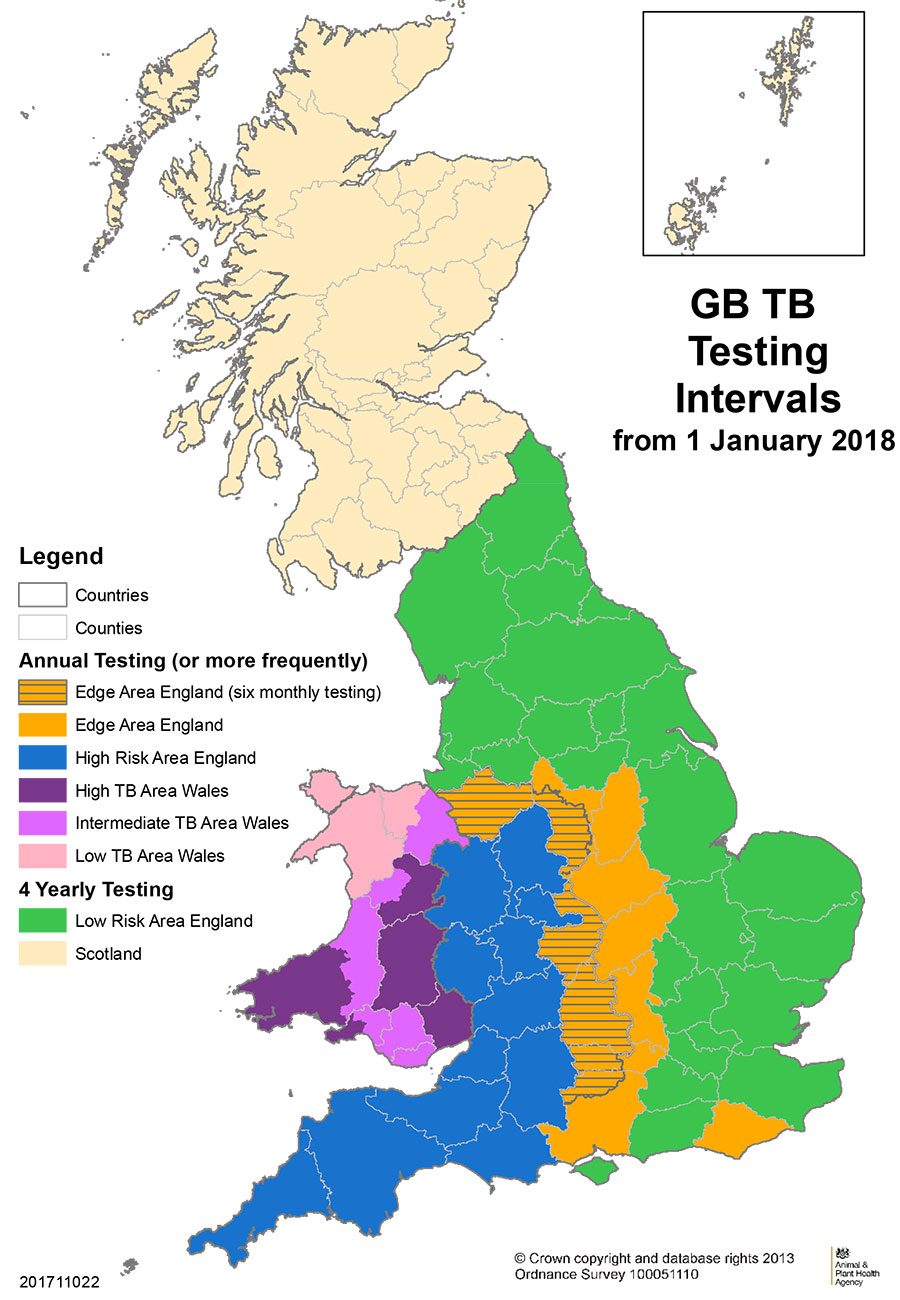

TB slaughterings down in High Risk Area, but Edge Area is a concern

The government’s latest TB statistics show that herd incidence and herd prevalence have decreased for the 12 months to June 2019, compared with the previous 12 months.

The total number of animals slaughtered due to a TB incident in England over this period was 32,413 – a 3.3% drop on the previous year.

The number of new TB herd incidents decreased by 3% in England in the 12 months to June 2019, driven by a reduction in the High Risk Area (HRA) of 204 new herd incidents.

However, in the Edge Area, new herd incidents increased by 13%, from 631 to 716.

The total of disease-restricted herds as a percentage of registered herds in England is 5.7%.

Bill Harper, the National Beef Association’s TB Committee chairman, said: “It is really worrying that TB is still developing in the Edge Area – and nobody is really grasping that.

“That’s our big concern. I speak to farmers across the country all the time. They say: ‘We can see it coming’.”

Cattle herds in the Edge Area counties of Cheshire, Oxfordshire, and Warwickshire, and in parts of Berkshire, Hampshire and Derbyshire, are now subject to routine six-monthly surveillance testing.

Alongside these more regular testing intervals, the introduction of infected cattle and possible exposure to infected badgers have been suggested as reasons for the spike in new outbreaks in the Edge Area.