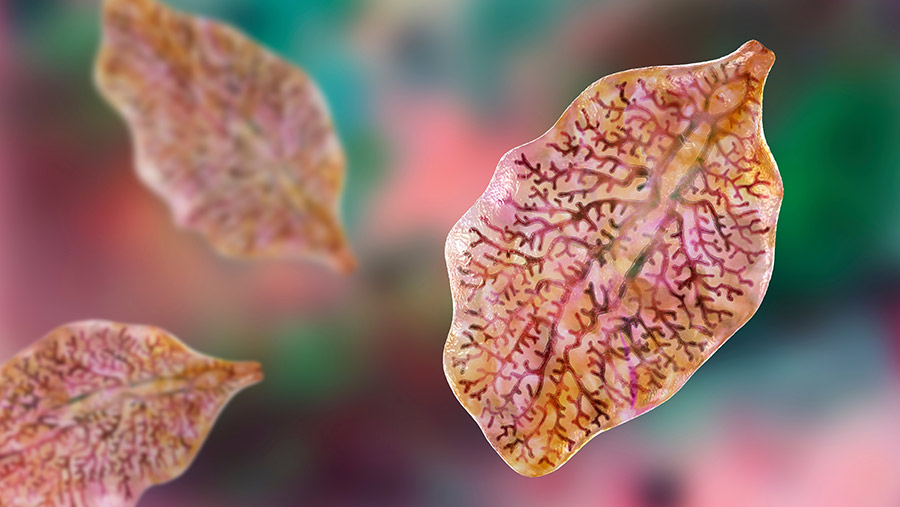

Liver fluke: Symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and prevention

© Dr Microbe/AdobeStock

© Dr Microbe/AdobeStock Liver fluke is a common parasitic disease of grazing animals.

Caused by the trematode Fasciola hepatica, it is endemic to our national herd and flock, so it is important to ensure you know how best to reduce the impact it has on your livestock health and business.

Fluke risk is greater when there has been consistent warm and wet weather – such as the weather we have seen throughout the UK this summer.

About the author

Changing weather patterns means liver fluke is becoming increasingly common in areas previously seen as low risk. Ellie Collins of Belmont Farm and Equine Vets offers expert advice.

As a result of changing weather patterns, liver fluke is occurring more frequently in areas that have previously been considered as low risk.

See also: Video: Fluke video gives powerful insight into parasite

The liver fluke life cycle requires an intermediate host, the mud snail. This means it is associated with damp, poorly draining pastures where mud snails thrive.

However, any pasture can become contaminated if the parasite burden is high enough.

Risk period

The essential role the snail plays in the liver fluke life cycle means the adult fluke can only reproduce during the summer months.

As a result, the infective stage of the fluke is generally present on the pasture from late summer/early autumn onwards and at a high risk of being ingested by livestock before housing.

It takes six to eight weeks for the fluke to move from the intestines to the liver. Here, they mature to egg-laying adults, approximately 10 to 12 weeks after being swallowed.

During their migration through the liver, immature fluke cause extensive damage to the liver tissue, which can be seen in a post-mortem.

This damage, as well as the collection of adult fluke in the bile ducts, is the cause of clinical signs seen in animals infected with fluke.

Symptoms

Symptoms of liver fluke infection (fasciolosis) vary depending on the number of parasites ingested, the time of year, and the type of animal affected. In all cases, death can occur.

- Acute fasciolosis This is seen in the autumn and is caused by the ingestion of large numbers of immature fluke.

Sudden death is the result of blood loss into the liver or secondary clostridial disease (Black’s disease). - Sub-acute fasciolosis Seen in late autumn/early winter. Symptoms are loss of condition or failure to thrive, lethargy, weakness and scour.

- Chronic fasciolosis Occurs in late winter and spring/summer and has similar symptoms to sub-acute fasciolosis. A further symptom is development of a bottle jaw or swelling below the jaw.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of fluke can be suspected by clinical signs but must be confirmed by laboratory tests. Confirmation can be by the presence of adult fluke within the liver on a post-mortem examination, or by the presence of fluke eggs in a faecal sample.

It is also possible to perform a lab test on blood (copra antigen or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay test) or milk, although this is a marker of historic exposure rather than confirmation of an active infection.

Treatment

Treatment can be effectively achieved with drenches. These must be timed carefully to ensure they have maximum effect and minimise the induction of resistance to flukicides in your fluke population.

Different flukicides are effective at different stages of the life cycle and, as such, a specified window of time must be left between access to infected pasture and treatment.

Understanding which treatment is the most suitable choice for your livestock and management system, and how to use this treatment to maximise efficacy, is important.

This can be advised on by your vet or discussed at your health plan.

Recovery from heavy infestations takes time and supportive care, which should be based around easily available, good-quality nutrition and movement to clean pasture to reduce re-infection.

Prevention

Prevention takes many forms and should include the following:

- A flukicide treatment strategy discussed with your vet at your herd health plan, ensuring appropriate dose rates and medicine choice

- Ensuring grazed pasture has good drainage to minimise the amount of suitable habitat available to the mud snail

- All bought-in stock should be treated and suitably quarantined on arrival; this protocol should be discussed with your vet

- Fencing off wet grazing areas, where the mud snail is more likely to exist

- Avoiding grazing at-risk pastures during autumn and winter.