Stamp Out Lameness: Culling repeat sufferers

It’s all too easy to retain a chronically infected lame ewe in the vain hope she’ll eventually recover, but by doing so producers could be stopping themselves from ever truly getting on top of lameness.

According to sheep farmer Graham Dixon, Alwinton Farm, Rothbury, retaining problem ewes will result in more infection and more work.

“If you keep persistently infected (PI) ewes, you will get possible cross-infection, resulting in more and more PI ewes and more time dealing with problems.

“If you can substantially reduce lameness incidence, you can spend more time doing other things rather than chasing sheep. There’s also the welfare implications of lame sheep and the costs associated with reduced productivity.”

PI individuals are a constant source of background infection, explains vet Matt Colston, of Frame, Swift and Partners, who says re-infection rates are stopping most farmers from getting lameness levels down to reasonable levels.

PI individuals are a constant source of background infection, explains vet Matt Colston, of Frame, Swift and Partners, who says re-infection rates are stopping most farmers from getting lameness levels down to reasonable levels.

“If lameness can be kept below 2%, producers will be rewarded with less work and more productivity.”

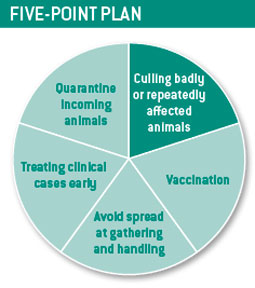

However, Mr Dixon – who was involved with FAI Farms in designing the five- point plan (see chart) – stresses that although culling is important, it is not the most crucial element and should be used as part of a whole approach.

“Culling is a last resort – basically if you want a lameness-free flock and they won’t respond to treatment – you don’t have an option.

“There is a cost to culling, for example, the cost of replacements is usually higher than cull value. It is a question of judgement and how much time you have spent on a ewe.”

However, he also says, although replacement costs are worth considering, the hidden costs from reduced productivity are significant.

“If you can substantially reduce lameness incidence, you can spend more time doing other things rather than chasing sheep. There’s also the welfare implications of lame sheep and the costs associated with reduced productivity.”

Graham Dixon

Mr Colston says there is room for everyone to reduce the “massive” hidden costs from lameness, as well as labour input:

“I don’t know any flock that doesn’t complain about spending too much time doing feet. By managing properly you can get the time spent with lame sheep down to a minimum.”

Mr Colston explains how adopting a “three strikes and you’re out” rule for lame sheep allows sheep the chance to recover, before removing them from the flock (see cull strategy diagram, left).

Culling of chronically infected animals, and adhering to the other points in the five-point plan, has helped Mr Dixon cut lameness by 75% over three years in his flock of 1,200 ewes.

At the start of the programme, 5-10% of the flock were culled for lameness, however this has now dropped to 3%. Such a reduction in culling level over time is a pattern likely to be seen on most farms taking such an approach to lameness.

“When selecting culls, we look for PI ewes, those that do not respond to treatment over a period of time,” says Mr Dixon.

“We may identify lame sheep with spray, but good stockmanship is important so you know your lame ewes. Culling is always a last resort.

“Prompt treatment of infectious lameness is also crucial – as soon as you see a problem it’s important to do something where possible. In a field situation this can be difficult, but you need to assess the extent of the problem.”

| Think cull |

|---|

| Cause: What’s the reason for lameness on your farm? Understand: If you retain infectious ewes you will never get on top of the problem Locate: Identify problem ewes and implement the three strikes and you’re out strategy Learn: About the five-point plan and how the other four steps can help cut lameness |

Mr Dixon will spot treat problem animals if there are only a couple of infected individuals. However, when 20-25 are lame, for example, he says it is worth gathering them up and running them through the handling system.

He also advises foot-bathing whenever stock are handled where infectious lameness has been identified.

Mr Colston stresses that although handling ewes for targeted treatment and foot-rot vaccination may be challenging for larger flocks, this should not be an excuse for not tackling the problem.

“It’s convincing farmers, and particularly bigger flocks, it is possible to set up their system to enable routine catching and treatment.

“It will often involve a change in mindset, but producers need to ask – what can I do to change my system so I can handle more easily? If lameness is something you want to address, there are options that everyone can do.”

Mr Colston explains that although initially a large number may need to be targeted for treatment, this would drop as lameness incidence was reduced. With a target incidence of less than 2%, this would only equate to 60 ewes from a 3,000 ewe flock, for example.

Summary of lameness control at Alwinton Farm:

- Culling persistently infected ewes

- Vaccinating for foot-rot

- Moved handling set-up from an outdoor system on gravel to an indoor set-up on concrete

- Handling system is pressure washed after each use

- Foot-trimming is only used where essential and not as a routine measure – unnecessary trimming can create an infection risk

- Prompt treatment of problems

- Foot-bathing with Formalin where necessary – this year, April-born lambs have been bathed once, and will potentially be run through a further four times

- Liming around troughs and lay areas

- Quarantining of bought-in ewes and rams

- Bought-in ewes are foot-bathed off the wagon and vaccinated for foot-rot

- Rams are vaccinated and spot treated where necessary

- Foot-rot and scald has dropped from 10.25% to 2-2.5%.

Cull strategy

Assess lameness

- Gather the whole flock and determine the cause of lameness on your farm

- This is a good point to get your vet or health adviser in to assess any problems- often what a farmer may call foot-rot may be something else, for example

Target

- Target antibiotics at individual sheep with active infections

- Shed off these treated animals and keep in a separate group

Record

- Identify these treated individuals with a spray mark and record treatment

- Re-examine them one to two weeks later to see if they have recovered from infection

- When a second treatment is needed, record and spray the individual with another mark

- If possible, also assess the whole flock again, two weeks after the initial assessment

Cull

- Assess the separated, treated individuals for a third time about two weeks after the second treatment

- Any stock requiring a third treatment should be culled out of the flock.

Campaign aims

- To highlight the industry concern and the FAWC Opinion report

- To get farmers to adopt the national five-point plan to tackling lameness

- To aim for a lameness incidence of 5% or less by March 2016 and of 2% or less by March 2021

Get involved

Online: For more information on the campaign, visit www.fwi.co.uk/stampoutlameness

Events: Lameness will be a topic up for discussion at NSA Sheep 2012 on 4 July. FAI Farms is also hosting two lameness events on 28 June and 11 September. More details can be found on the campaign website.

Forum: Share your lameness stories at www.fwi.co.uk/livestocklines

Email: sarah.trickett@rbi.co.uk

Post: Stamp Out Lameness, Farmers Weekly, Quadrant House, The Quadrant, Sutton, Surrey, SM2 5AS.