Deer farming meets consumer demand for more venison

© FLPA/REX/Shutterstock

© FLPA/REX/Shutterstock Venison may have once been the preserve of upper classes, but consumer demand has soared recently, presenting a real market-driven opportunity for UK farmers.

Sales of venison have grown by 20-25% annually over the past four years and there is a shortage of domestically-reared meat, according to the boss of one of the UK’s largest venison processors.

Holme Farmed Venison‘s Nigel Sampson says there is an urgent need for more deer farmers to plug the gap in supply being met by imports from as far afield as Poland, Slovakia and New Zealand.

Supermarket price promotions have played a big part in the surge in UK demand, having made venison accessible to a wider range of consumers, he says. “The retailers have been very important – it’s through them that we’ve seen the big volume change and an entirely new customer base develop.

“We’re also seeing a healthy increase in the catering sector where sales have doubled over the last 12 months.”

Ultimately the health image of venison has been its strongest selling point, Mr Sampson says. The meat is low in fat and cholesterol, high in iron and has been officially recognised by the Food Standards Agency as a source of Omega 3.

Because of these qualities, he is confident the sector’s growth is not a flash in the pan, despite admitting that price promotions have held up sales through the recession. “People are now buying venison for its own qualities and sales have even started to overtake more traditional meats in some areas.

“Demand is expanding as fast as it can, so now we really need to address the supply.”

Investing in the future

Mr Sampson’s long-term confidence in the sector is reflected in the investments that have been made at Holme Farmed Venison’s factory and at his own 110-acre Yorkshire farm, where 400-500 Red deer are finished each year.

HFV has invested more than £1m over the past five years in its 10,000sq ft factory outside York. The facility, originally set up in the early 90s, processes the equivalent of 15-20,000 animals a year (4000 from the UK) into a range of products, from steaks to burgers.

Products go to supermarkets including Booths, Asda and Sainsbury’s, plus catering companies, wholesalers and local butchers. The company, which last year had a turnover of £4m, also has an online mail order system.

“The supermarkets have been a real success story for us. Booths was our first retail customer and carries the biggest range. We’ve increased the number of Asda stores from 36 eight years ago to more than 300 now and our allocation in Sainsbury’s stores doubled last winter.”

HFV pays farmers on a dead carcass weight basis, with prices currently at £4-4.50/kg DW, around £1/kg DW more than a year ago; a reflection of the tighter market, he says.

Mr Sampson admits balancing carcass utilisation throughout the year is a challenge, especially as the tight supply of deer means he cannot be too picky about carcass quality.

“Marketing of deer becomes harder the bigger they get. Red deer are naturally the right size for our buyers but, if the loins get too big, the restaurants won’t be able to afford them,” he says. Typically deer will be slaughtered at 18 months old, at a weight of 45-55kg DW – a killing out percentage of about 58%.

Winter is the peak time for sales of steaks, diced meat and wholesale supplies for use in ready meals, while sausages and burgers do well in the summer months, he notes.

The meat itself can be tricky to work with as it oxidises in air within 40 minutes, losing its redness. Carcasses are therefore broken down and vacuum packed soon after slaughter to prevent this discolouration and maintain freshness.

Getting involved

The low labour requirement for deer farming means it can easily compliment other livestock and arable enterprises. But any farmer going in to it for the first time still needs to be fully committed to making it work, Mr Sampson cautions.

The cost of fencing paddocks, raceways and handling areas, plus any building conversion, can soon mount up and a minimum of a 100-head unit is ideally needed, he says. A finishing unit of this size would require an initial capital outlay of about £30,000.

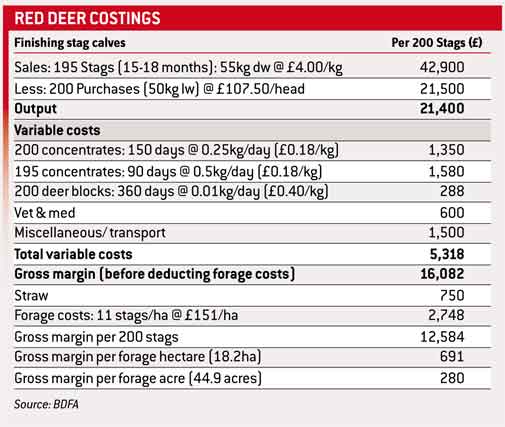

Most UK deer calves originate from the Scottish Highlands and islands such as Jura, where the cost of feed and distance from market make it more economical for many breeders to sell calves for finishing further south. Calves are typically sold at 5-6 months old (45-50kg liveweight) to finishing units, where they will double their weight before being slaughtered at 15-18 months-old (see costing table).

Deer are generally grazed on grass as long as the weather and soil conditions allow, with silage and concentrates used to supplement grazing. “Deer are fantastic converters of grass to lean meat, so their management is really all about efficiency of grazing. Ideally you need a sward three or four inches high.”

They have the ability to maintain body weight through winter on relatively little feed, which helps keeps costs down even when animals are housed, Mr Sampson adds. Even when animals put fat on, it tends to form around the outside of the muscle rather than within the meat, making it easier to trim from the carcass, he says.

Worming may be required at turnout in the spring to protect against lungworm and fluke, with a follow-up treatment in the autumn if needed. Stags have antlers removed in October, largely as a safety precaution for both the deer and anyone handling them during enclosed feeding or transport.

At Mr Sampson’s own farm he has recently invested £100,000 in a new Roundhouse building to house the farm’s deer over winter. The building offers 340° of open sides, which allows animals to settle more quickly and improves airflow – reducing incidence of problems such as pneumonia.

Deer are penned in family groups of up to 70 calves in a pen and bedded on straw. “Everything we’re doing is about trying to minimise the amount of stress on the animals when they are housed indoors and make it as easy as possible to manage their movement.”

The future

Mr Sampson, who plans to increase his own herd to 600-head, is bullish about the future for venison demand and is keen to see more UK-sourced meat on the shelves.

The BDFA is working with the UK’s 180 country parks to get “park standard” venison from Red and Fallow deer into the wider supply chain. “This could dramatically boost the amount of UK raw material available and I think the parks will have a big part to play in the next two or three years, potentially displacing some of the reliance on imports,” he says.

But he is keen to ensure that all venison retains its naturally-produced image and suggests that the phrase “farmed venison” could be misleading to consumers given the low-input systems used anyway.

“Consumers want a product that’s been produced in a natural way with as little human interference as possible. At the same time they want a consistent, quality product, so there has to be some modernisation, or farming, in that process wherever it comes from.”

Marketing will be a key focus for the future and Mr Sampson sees the internet as an important way of educating consumers and farmers about deer farming and the benefits of venison.

“There are few market-led opportunities like this, so I’m keen to get the story across to all involved. In particular, it’s about time more emphasis went back to the farming side.”