Why low-mastitis herd keeps a close eye on medicines cabinet

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan The downside of a dairy herd with less than 5% mastitis is having to maintain a stock of in-date antibiotics.

This is the case for the Hodginkson family, who run a 150-cow Holstein herd at Harley Grange, East Sterndale, in Derbyshire.

Their 162ha (400-acre) all-grass farm sits at 333m.

See also: How MilkSure training helps cut medicine milk failures

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Lynne and Mark Hodgkinson, who farm in partnership with their son James, also rear all 350 youngstock from the herd (two-thirds dairy, one third dairy beef finishing off grass at 18-24 months).

They also run a 300-ewe flock lambing on 1 April to a Beltex tup.

About 60% of cows calve between October and December, with no calvings from April until June as the farm is not designed for early spring grass, says Mark.

Grazing is from 10 May until the end of October, when the weather allows, and yields average 8,500 litres.

Apart from a self-employed worker two days a week, the farm labour relies on family.

James does 90% of the milking, with relief supplied by Mark. Cubicles are limed and bedded with sawdust on good-quality mattresses every other day.

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Consistency

Such consistency achieves results: “We get very little mastitis: in 2023, we had six cases – equivalent to 4.19 in 100 cows – and a cell count of 99,000 cells/ml,” says Lynne, while Mark adds: “We have never had a bulk tank failure.”

Having used the Delvo test to check milk before it went back into the tank, they tested its effectiveness by monitoring milk from cows treated with antibiotics.

They also did this following calving when animals had been tubed at drying off.

Mark says this is when they realised how “very sensitive and reliable” the test is, because as soon as milk was allowed to go back in the tank, the test results confirmed it.

However, renewing their MilkSure training (covering antibiotics residues in milk) earlier this year, at the request of their milk buyer, gave the family a refresh about antibiotics storage and management.

Sitting down with their vet, Annemarie Fitzgerald from Derbyshire Veterinary Services in Buxton, made them think, says Lynne: “It makes you realise you know more than you give credit for; you just do it as part of the job.

“We were reminded about use-by dates and withdrawal periods for off-label use.”

In-date antibiotics

While they did not have to make any major changes after the training, Lynne admits to monitoring the medicine cabinet more closely: “It’s more a problem for us of something going out of date – some products only have a one-year date range.

“We always keep some milking tubes in stock and run the risk of having to send some back to the practice out of date, as they only come in boxes of 20,” she explains.

Cows have been teat-sealed at drying off “for years” and only animals with cell counts of more than 200,000 cells/ml are tubed as well.

Last year, this amounted to just 12 cows, which, again, increased the risk of antibiotics going past their use-by date before they were needed.

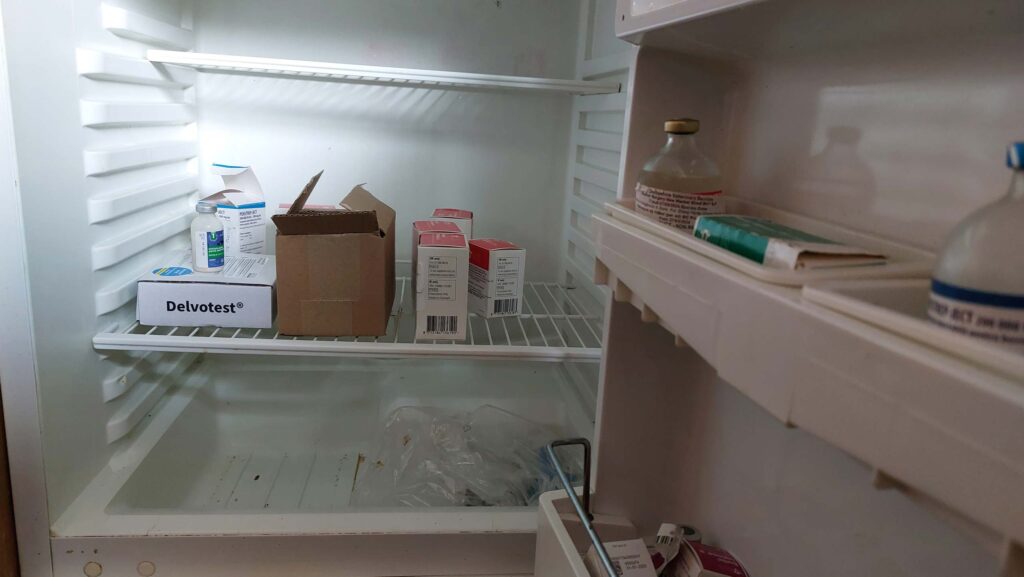

Lynne keeps a separate fridge in the kitchen for any farm medicine that needs to be kept cold, with a second, locked medicine cabinet out on the farm for storing all other medicines, anti-inflammatories, or wormers.

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

All antibiotics use

Annemarie, whose dairy clients range in size from 50-cow to 300-cow herds, says that the practice might see 10 tank failures a year.

For her, MilkSure training emphasised the importance of the whole farm picture when it comes to antibiotics use.

“When a client has had an antibiotics failure, I used to go through the BCVA [British Cattle Veterinary Association] checklist, but this [training] made me look in more detail and ask more questions about what’s going on elsewhere, asking about other medicine use on the farm at the same time, such as antibiotics to treat digital dermatitis,” she says.

She encourages clients to regularly sample mastitis cases to formulate a treatment plan and to use a cow-side mastitis test before automatically treating suspected cases.

This is because the first line of action might just be using an anti-inflammatory, she says.

It is this renewed appreciation of the importance of antibiotics on dairy farms that has helped the industry to lower use.

MilkSure training has more than halved the bulk tank failure rate, says vet Owen Atkinson of Dairy Veterinary Consultancy, who has trained more than 713 vets in the programme since it began in 2017.

© MAG Shirley Macmillan

Bulk failures halved

“Then, the failed rate reported by the laboratory, which does the vast majority of bulk tank testing for milk buyers, was 0.25%, and last year it was 0.1%,” he says.

“Training has had a huge impact on the industry, not least because vets are more “savvy” about the importance of being on top of the game when it comes to antibiotics residues in milk, as well as use of all medicines on farms.”

With 2,500 farms having completed the course up to early 2020, Owen says that 40 farmers a week are taking the test.

He stresses that the aim is to protect dairy farming’s reputation to the general public.

Antibiotics residue testing is highly sensitive because it aims to safeguard exports.

Overseas countries look to see if there is any detectable residue, not just whether whey powder or cheese, for instance, is under maximum levels, he explains.

Some milk buyers make the course compulsory as a preventative, others only if a farm has a bulk tank failure. This makes it “a bit like a speed awareness course”, he says.

Everyone on farm who milks cows – including the relief – is encouraged to complete training.