How can dairy farmers tackle the risk of inbreeding?

In the UK, inbreeding levels for breeds stands at about 2%. While this figure is significantly below the 6% recorded in the US, UK inbreeding is rising at a significant 0.13% points a year*. As this national figure rises there will be a negative impact on performance and more genetic defects will come to the fore.

Inbreeding is becoming more of an issue because selection for higher production and improved type of dairy cattle has reduced genetic diversity. Today, a limited number of animals in each breed serve as parents of highly influential sires in each generation.

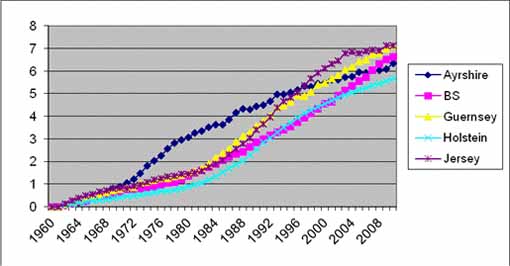

There are a number of emerging inbreeding trends within dairy cattle. The Jersey is now the most inbred breed in contrast to the Holstein which is the least (see graph one). No matter what the breed, the impact of inbreeding on any herd has a detrimental impact on a producer’s bottom line because it increases the chances of recessive conditions. It reduces production, longevity, fertility and it can also lead to genetic defects like Complex Vertebral Malformation.

The latest research from the United States also reveals a new genetic defect caused by inbreeding. The United States Department of Agriculture has discovered five haplotypes, which are stretches of chromosome that are transmitted as a unit from one generation to the next. The research, which analysed genomic evaluations suggests that haplotypes have a recessive mode of inheritance and can potentially cause embryo loss when a heterozygous sire is mated to a heterozygous dam.

What does inbreeding mean in financial terms?

Typically, a 1% increase in inbreeding costs results in a loss of 34kg of milk a lactation, a reduction of 13.1 days of productive life and a £14.11 loss in lifetime net income. This has led to an inbreeding level of 6.25% being set as a best practice threshold that farmers should not cross (see table 2).

What steps can dairy farmers take to fall below this level and minimise inbreeding?

The first step is to gain an understanding of inbreeding levels on an individual and herd basis by keeping good breeding records. Farmers who are milk recording can obtain genetic information from the National Milk Records which will indicate the inbreeding level for every individual animal as well as whole herd levels.

However, farmers face a real challenge to analyse this data manually due to the scale of the task. With inbreeding typically occurring three or four generations back, I would recommend that farmers need to look back five generations when selecting new bulls. This is a significant time challenge for any commercial farmer.

While dairy farmers must continue to look at the bull proofs for the best performing sires (based on a Profitable Lifetime Index, high type, high production, good health and fitness traits) they also need to look closely at pedigree to ensure the bloodlines they choose won’t raise inbreeding rates within the herd. When the bloodline of a cow is the same they need to choose a sire with an outcross bloodline.

Maintaining records and analysing pedigrees is a complicated process. Yes, it can be done manually, but I do believe that computerised mating programmes are the most consistent, reliable and expedient way to provide farmers with pedigree information on at least five generations.

Critically, a good mating programme should not only provide this data analysis, but it should also provide farmers with clear independent guidance to help them select the right sire to avoid inbreeding.

All farmers need to make genetic progress while reducing inbreeding within their herd. Understanding the level of current inbreeding as well as being able to access immediate information on ancestors is essential to making informed breeding decisions that will lower inbreeding levels.