Close the door on metabolic disease

All producers know that as soon as a cow develops milk fever, it’s a slippery slope to a host of other disorders which all have a negative effect on her overall performance.

In fact, vet James Husband says one metabolic disease opens the door to many others, as there is a strong relationship between the main metabolic disorders of dystocia, retained placentas, metritis, displaced abomasums, mastitis and reproductive disorders.

These problems are all linked to reduced conception rates and the consequential cost to the UK dairy industry is considerable.

Cost

Mr Husband calculates clinical milk fever alone costs about £250 a case. With an average incidence of about 7%, this equates to a cost of £1,750 for a 100-cow herd.

However, he says the cost of sub-clinical milk fever could be far higher. “Sub-clinical cases may not bring the classic signs of milk fever, but low blood calcium will mean it is more likely for these cows to be culled and more likely they will develop retained cleansings or displaced abomasums (DAs).”

(DAs) alone can cost between £400-600 a cow, and with an average incidence of about 2% this equates to £800-£1,200 for a herd of 100 cows.

“The incidence of DAs is related to milk yield and will be higher in herds yielding more than 8,500 litres,” he says.

“In herds producing more than 10,000 litres a cow a year, it is common to have an incidence of 5%. However, whatever the yield of the herd, producers should be targeting an incidence of less than 3%.”

The precise UK incidence of ketosis is not known, but Mr Husband says this could be 10-15% in the first six weeks post-calving. “Cost relates to decreased fertility, increased risk of culling and other diseases,” he says.

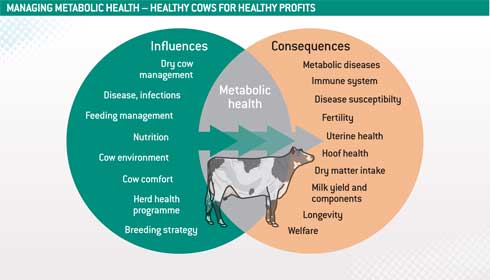

Cow comfort and environmental factors play a part in the causes of metabolic disease, but nutritional deficiencies, in particular negative energy balance in the transition period, is an important cause.

The transition from gestation to lactation dramatically increases requirements for energy, glucose, amino acids and other nutrients in dairy cattle.

Negative energy balance

Negative energy balance suppresses immune function, leading to metabolic disorders. Mr Husband says this potentially explains the relationship between infectious and non-infectious transition disorders.

High non-esterified fatty acid levels in the two weeks prior to calving are associated with increased risk of DAs retained placentas and a higher chance of a cow being culled.

Mr Husband, who is a member of the European Board of Bovine Experts – which was established to consider modern dairy cattle management and nutrition challenges and offer advice to the industry – says a cow is most vulnerable in the period around calving. Risk is particularly high if dry cow management has been poor and inappropriate rations have been fed.

Higher-yielding cows are more likely to suffer from excessive mobilisation of fat stores when lactation begins and it is extremely difficult to prevent this. Mobilised fat stores have to be processed mainly by the liver. When the amount of fat is excessive, liver function can be severely affected and this leads to increased risk of diseases such as displaced abomasums and ketosis.

Cows are also more likely to suffer from mastitis and womb infections. “Milk fever makes this worse, affecting immune function, energy status and retained cleansings,” says Mr Husband.

| Preventing metabolic disease |

|---|

There are numerous measures that can be implemented to reduce metabolic disease, including preventing overfeeding and not allowing cows to get too fat in late lactation and during the early dry period. “Practically, this may come down to being able to process straw well enough so cows will eat it in sufficient quantities in the far-off dry period,” says Mr Husband. He says milk fever could be prevented by ensuring adequate magnesium levels in the ration and selecting forages with a low potassium content for the dry period. This often means restricting first-cut grass silage to transition cows. Other preventative measures:

|