Claw horn lesions: what they are, the causes and treatment

Lameness, usually caused by injury or disease to the foot or leg, has the potential to affect an entire herd.

Losses arise from treatment, decreased yields, reduced fertility and longevity – and cost £180 a case on average, according to AHDB estimates.

See also: 4 ways to improve cow flow and reduce lameness

Unlike other cattle illnesses, such as mastitis, there has been little scientific research into lameness, but what vets and farmers do know is that claw horn lesions are responsible for a large number of lameness cases.

Farmers Weekly found out more about it, the causes and how to treat it.

Q&A with Jon Huxley, professor of cattle health and production at Nottingham University

What are claw horn lesions?

Claw horn diseases include sole ulcers or haemorrhages and white line disease, and are a result of increased pressure on a cow’s foot.

Claw horn lesions are a pressure lesion. All the weight of the cow bears down on the wedge-shaped bone – the distal phalanx – attempting to squash the layer of cells that create the sole.

As soon as the cells start getting slightly squashed, the first thing we see is blood being incorporated into the sole – a sole haemorrhage or bruising.

If they are squashed really badly, it kills the cells and that’s when we see a sole ulcer.

A sole ulcer is actually just a defect in the sole, because the cells have been squashed so badly that they can no longer produce the sole. Understanding why the cells are at risk of being squashed is the key to preventing lameness.

What causes it?

Claw horn lesions are caused by three main influences:

- the environment

- calving

- changes to the structure of the foot.

A cow’s environment can cause excess pressure on the dermis and the factors will depend on the management system on farm. This can include standing time, concrete, cubical comfort and how often foot-trimming is carried out.

The destructive nature of calving on the cow can also lead to claw horn lesions. In order to make calving possible, a cow has to degrade all of the connective tissue that holds the pelvis and the reproductive tract in the lead up to birth.

The tissue that attaches the bone to the hoof wall also degrades, meaning the bone moves around more immediately after calving – putting the thin layer of critical cells under more pressure.

“While we can’t change or stop this, what we can do is manage the interaction between calving and the surrounding environment. (See ‘Bone damage’)

With additional stress on fresh heifers being incorporated into the milking routine post-calving, it’s really important to keep a focus on this group, adds Prof Huxley.

“There is a real danger that we ruin first-calving heifers within the first few months of lactation because of all the pressure that goes on their feet post calving.”

The digital cushion – the pad of fat that sits on the bone – also plays a key role in preventing lameness. There is the question of whether the thickness of the fat pad is linked to body condition score.

“We now think it has become a vicious circle – particularly in the case of the Holstein cow – because the cow loses body condition to peak yield.

This thins the digital cushion, on top of the calving problem, and that makes them lame – consequently causing dry matter intake to drop and cows become even thinner.”

It’s this theory that explains why lameness is seen more often in higher-yielding cows.

Optimal body condition score to prevent lameness is 2.25 – anything less than this starts to cause problems. However, the loss of condition from any starting point is also an issue.

How do you treat and prevent them?

Traditional methods of treatment include therapeutic trimming, using a block and/or treating the cow with an anti-inflammatory.

Unfortunately, compared with something such as mastitis, the evidence behind treatment methods for lameness is non-existent – it has never been tested to see what the best option is.

AHDB-funded research into the treatment of claw horn lesions – in partnership with Nottingham University – which has revealed some pretty impressive results.

In one of the studies, 1,000 cows were monitored on five farms. These animals were mobility scored every two weeks, using the AHDB mobility score chart.

Cows identified as having mild cases of claw horn lesions were randomly assigned different treatments – from just a trim to full treatment of a trim, block and a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (Nsaid).

After five weeks, results showed 56% of cows that received full treatment were sound (score 0) and 85% were no longer lame (score zero to 1).

The trials also highlighted the importance of detecting lameness at the earliest possible stage.

The test was repeated on 1,100 chronically lame cows, and data revealed that, even with full treatment, only 16% of cows weren’t lame after six weeks.

“In reality, animals that are chronically lame don’t ever seem to get right again – it’s essential to focus treatment on early lame cows.”

Claire and David Webb, Tockenham, Swindon, Wiltshire

Relieving pressure on feet using rubber matting

Preventing claw horn disease all comes down to reducing pressure on the feet, as Claire and David Webb have discovered.

They improved cow comfort for their 270-head Holstein Friesian herd through using rubber matting at their family farm in Tockenham, near Swindon, Wiltshire.

“We installed rubber matting in the parlour, the collecting yard and at feed faces about six years ago to increase cow comfort and cow flow,” explains Mrs Webb.

“You can see a real difference compared with concrete – the cows have much more confidence on it.”

Claire and David Webb found installing rubber matting on their Wiltshire farm improved cow comfort

Severe grooving in the concrete in the collecting yard highlighted further how useful rubber matting can be and how important it is to get concreting and grooving design correct.

“The grooving was done about seven years ago, initially to stop cows slipping,” says Mrs Webb. “While it was very successful at doing that, it has created a lot of lameness issues.”

Grooving was the main cause of lameness on the farm, with about 30% of the herd affected (score 2 and 3).

“We have considered planing the concrete to reduce the depth of the groove, but there is then the problem of fresh concrete causing further issues,” she adds.

“We see the cows head straight for the rubber matting rather than walking on the concrete, so it’s something we need to consider further.”

The effects of lameness on bone damage

Reuben Newsome carried out a PhD into lameness at Nottingham University during which he imaged the feet of sound cows and those that had been lame for prolonged periods, using an X-ray CT scanner.

The study found severe damage inside the feet of lame cows, and astonishingly this damage even affected the bone, with new bone growing around the sole ulcer site in cows that had been lame for prolonged periods.

The differences are evident from comparing the two pictures below.

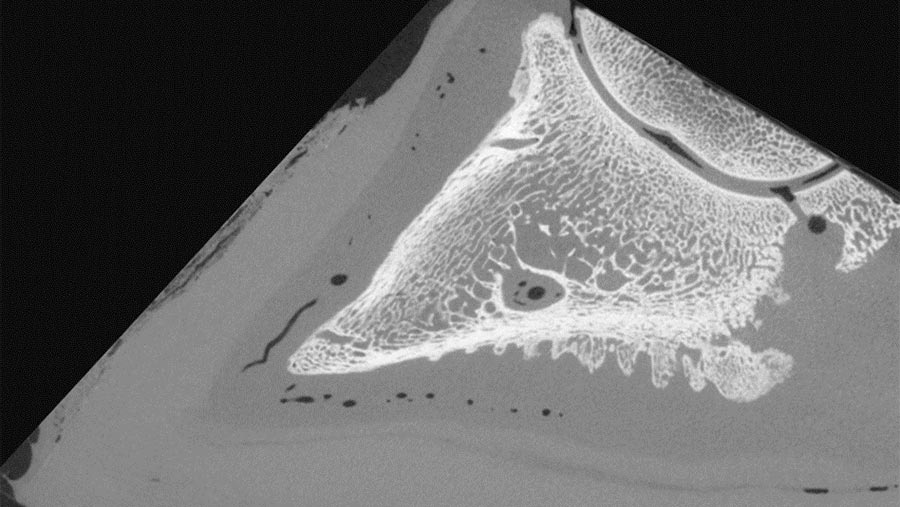

A hoof showing signs of lameness and bone growths extending from the pedal bone

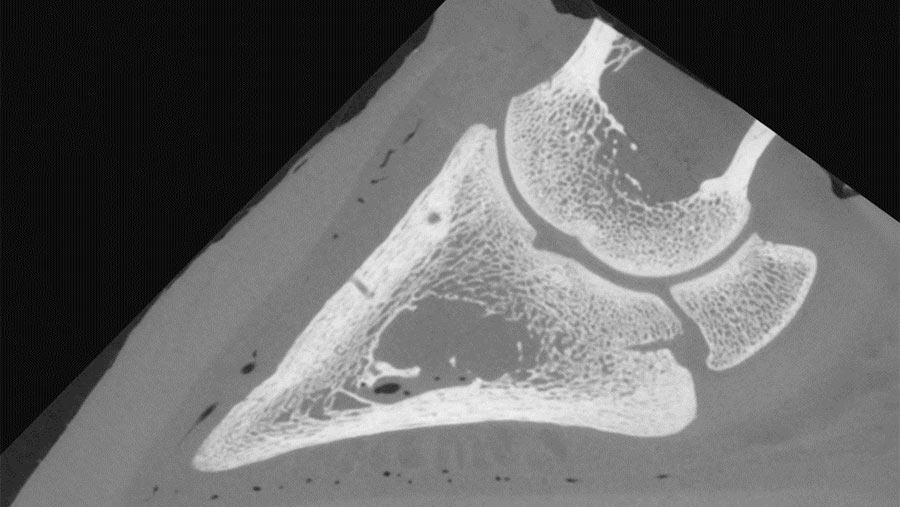

A healthy hoof with a smooth base

In the healthy claw, the pedal bone has a smooth base.

However, in the claw from the lame cow, new bone growths can be seen extending down towards – hindering the function and even replacing – the digital cushion.

It is likely these new bone changes are a result of chronic inflammation within the foot.

Once present the new bone causes further trauma to the region and further inflammation, leading to a vicious cycle of continued damage.

Once present, it is difficult to see how this would resolve so early detection is key, says Dr Newsome, farm vet at Synergy Farm Health.

“We know that early detection and immediate treatment of lameness increases cure rates and reduces repeat cases,” adds Dr Newsome.

“The best approach involves moving from spending fruitless hours repeatedly treating the chronically lame cows, to investing time wisely in preventing lameness, then detecting and treating immediately to avoid the chronic cases from developing.”

However, with this putting additional pressure on already limited farm labour and time, lameness control programmes are more frequently becoming part of veterinary services.

“We frequently mobility score on farms during afternoon milkings and produce lists of lame cows to be drafted out, then trim and treat all lame cows the following morning – alongside carrying out preventative trims.”