How farmers globally are adapting to survive volatility and climate extremes

© AdobeStock

© AdobeStock With increasing market volatility and extreme weather, how can UK beef producers adapt to survive?

We speak to three beef breeders from Australia and the US to find out how they have adapted their businesses to deal with climate change pressures and see if there are lessons we can apply in the UK.

See also: How US Angus breeder makes more beef from smaller cows

Case study: Jonathan Wright, Coota Park, NSW, Australia

Jonathan Wright © Supplied by British Cattle Breeders Club

Jonathan Wright is hoping to add value to his 500-cow herd by breeding for low methane emissions to create a low-emission beef brand.

Feed conversion efficiency has been a key selection trait for Mr Wright since he established his Blue-E herd of composite cattle 23 years ago. The farm has its own GrowSafe feed efficiency testing facility, and all Blue-E bulls sold have been tested for this economically important trait.

Farm facts

- Farms 1,215ha (3,000 acres) across four properties

- 500-cow herd comprises Beef Shorthorn and Angus composite Blue-E

- Last year, 94% of 400 steer calves were in the top 30% for feed efficiency

Now Mr Wright sees an opportunity to take this a step further.

“We need to understand there are protein alternatives [to meat] and the majority of those are much lower-emitting forms. It’s not easy to hear, but it is fact,” he says.

About 90% of methane emissions are produced before calves get to the feedlot. Furthermore, there is a correlation between feed consumption and methane production, he explains. With 70% of feed consumed by cows, Mr Wright hopes to select animals that eat less and produce less methane.

He has started a trial with Sydney University measuring methane emissions from 80 heifers. Information is captured via electronic identification (EID) tags, and methane is monitored while animal feed during a three-minute period.

The trial will assess animals inside and at grass, and the heifers will be reassessed as mature cows after they calve.

The idea is to roll out testing so other farmers can supply the brand.

“We need to give consumers permission to keep eating our product. There’s no silver bullet [for reducing emissions], but one that is here and now is genetics and we can start getting on with it.”

Case study: Steve Binnie, Mirannie Station, NSW, Australia

Liz and Steve Binnie © Mason Hubers

“Adapt or die” is the ethos of fourth-generation farmer Stephen Binnie, who has overcome fires, flood and a global pandemic to diversify and add value to his business.

“The only thing in today’s environment that will allow you to grow and continue to meet challenges thrust on you is your mindset and business agility,” he says.

Testament to this has been Mr Binnie’s ability to overcome adversity.

He and his wife Liz sold his family’s 98-year-old Hereford stud in favour of Wagyu genetics in 2015. But on the back of the drought of 2015-20, the beef price “fell through the floor” and cattle were worth 30% of their cost of production at about £100 a head.

Farm facts

- 7,000ha (17,290 acres)

- Scaling up from 400 to 1,000 Wagyu breeding cows

- Sells 200 bulls annually

- Runs Delta Wagyu, supplying semen to Europe, Africa and South America. Sold 50,000 straws of Wagyu semen to the UK last year

- Wholesale and retail business Binnie Beef

- Wagyu Wonderland events space for corporate functions, weddings and parties

- Sells carbon credits to large emitters

Mr Binnie saw the problem as an opportunity, establishing Hunter Heartland Wagyu, selling meat to China.

He adds: “Another problem came along when our prime minister questioned China over Covid and China shut down our beef exports.” Overnight, 95% of his business disappeared.

To survive, the Binnie family continued to adapt, and Binnie Beef was born to supply meat domestically.

“Instead of selling on a spreadsheet, we are now selling to the best restaurants in Sydney and Melbourne,” Mr Binnie explains.

Selling meat wholesale and retail also helped them balance demand during Covid, when restaurants were forced to close.

It hasn’t been an easy journey, he confesses.

“My father thought sacking off our Hereford genetics was an appalling idea. But sometimes you need to take a reality check, have a look at yourself, ask hard questions. We did and it has been good growth since.

“The only wrong decision is not making a decision. You need to adapt, or you will be left behind.”

Case study: John Maddux, Nebraska, US

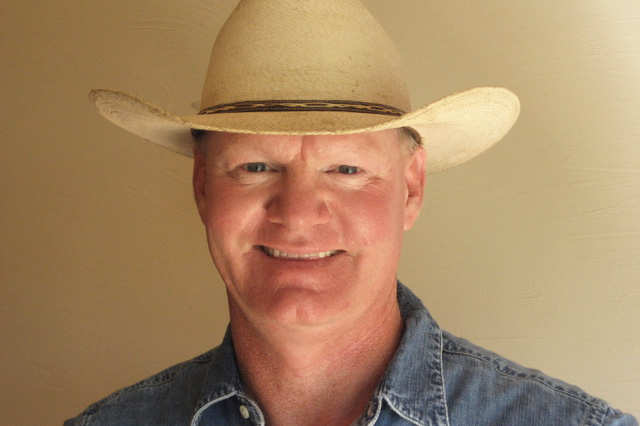

John Maddux

Breeding a composite cow that thrives on a low-input system is how beef producer John Maddux is lowering overheads on his extensive beef ranch.

The Maddux family exited the feedlot industry and now produce store cattle to supply feedlots. The business model relies on grazing cattle year-round with minimal supplementation.

Farm facts

- 18,210ha (45,000 acres, with rent about 15,000 acres)

- 2,500 composite females (three-quarter Red Angus, one-quarter Tarentaise and one-quarter South Devon, Devon and Red Poll)

- 1,000 replacement heifers

- Sells surplus heifers and bulls for breeding

- Produces store cattle for commercial feedlots

- 6,500 cattle on maize stalks this year

“We compare favourably with other farmers [in terms of profits] because year-round grazing gives us a real competitive advantage, mainly because we can cut our overheads so dramatically.”

Mr Maddux reckons his feed costs are roughly half in comparison to feeding a total mixed ration, see “Feed cost a head a day” table, below.

The foundation of the family’s success has been breeding a composite animal that will thrive in these conditions. Animals are selected for fitness traits, rather than production.

“In our system, having a cow that will go out and get bred and raise a calf trumps any high production.”

Cows calve at grass in May, and are sent to graze maize aftermaths with their calves in the autumn for five months, which are then weaned at 11 months. Large mobs of 800-1,000 cows graze 52ha (130-acre) plots for six to seven days before being moved to a fresh break.

“Farmers like us to take away the husks and leaves, so they can go in and no-till.

“We have been sending cows to corn stalks since 1975 and we have never gone with any supplementation unless there are severe snowstorms – and we’ve only had that three times.”

In these circumstances, six-wheel-drive trucks are used to deliver distiller grains.

Benefits of feeding on maize stalks

- Good compensatory growth at grass the following spring

- Encourages aggressive grazing

- Improves body condition of cows as they are only on the stalks for a few days before getting a fresh break, which means rations are consistent

- Calves weaned later at 11 months (opposed to six months) are healthier

- Heifers grazed with their dams are aggressive grazers

Mr Maddux says competition for rent has grown over time, but working hard to maintain good relationships has helped secure land over multiple generations.

He also buys 3,000-4,000 Angus calves annually and these are also wintered on maize aftermaths and supplemented with dry and wet distiller grains to target a gain of 0.4kg/day.

“We make them graze and hustle. We can winter a calf fairly cheap because of the availability of corn stalks around our ranch.”

He says it makes the animals more aggressive graziers when they then go to grass in the spring.

Feed cost a head a day |

|||||||

|

Animal |

Rent cost/ acre |

Number of days grazing/ acre |

Grazing cost a head |

Fence cost/ day |

Distillers cost/day |

Mineral cost/day |

Total cost a head a day |

|

Bought-in calves |

£14.66 |

70 |

21p |

14p |

44p |

5p |

84p |

|

Cows |

£14.66 |

35 |

42p |

18p |

None |

2p |

63p |

The farmers in this article all attended the British Cattle Breeders Club conference (27 January 2021).