Abattoir design critical to meat quality

Unloading animals at a slaughterhouse – it may be considered by some as the least important stage of the finishing process in terms of meat quality, but in fact, the opposite is true.

While genetics, feeding regime and environment on farm all have significant parts to play in the quality of the end product, those last few hours can be just as important as the previous two years spent rearing that animal, according to RWM Food Group’s agriculture director Richard Phelps.

“Lairage is so important when it comes to meat quality, all the hard work and money invested in finishing an animal can be undone when an animal is stressed in the run-up to slaughter,” says Mr Phelps, who’s food group is responsible for slaughtering about 2200 cattle a week at Langport.

Stress makes the pH in the tissue of cattle increase, which can cause the meat to become dark, firm and dry. This is why it’s important farmers take a look at the place where their animals are being slaughtered and make sure their welfare is optimum, explains Mr Phelps.

Cattle unload themselves as the tail-board lays flat on the floor.

The influence of stress on meat quality was so important that Langport invested in a new lairage and handling system four years ago based on the curved race design of leading animal behaviourist Temple Grandin. She also later visited the slaughterhouse and advised on some new additions that could further enhance the environment.

One of the key considerations when redesigning the lairage was including lots of natural light, explains Mr Phelps. “Natural light means it doesn’t feel part of the abattoir environment and when cattle arrive they just settle,” he says. Light is also important at the stunning stage, with a green light used to attract animals in to position, adds Mr Phelps. “Cattle are naturally drawn towards light, but not extremely bright light, and research has found green light will attract cattle.”

But the consideration for animal welfare goes beyond lighting and at this abattoir begins as soon as the animals are unloaded, with the unloading ramps positioned so the tail-board lays flat on the floor. “This means the cattle essentially unload themselves because the board is level with the ground and no sticks or goads are needed.”

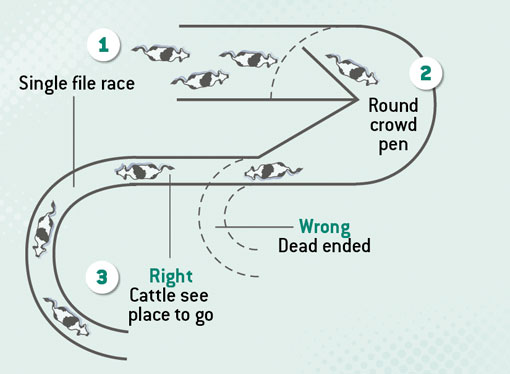

Once in the building, cattle are left to settle for a couple of hours before being moved in to the race. “The race is where the big improvement has been made,” explains Mr Phelps. “We have gone from a system that had a straight chute and dead ends, which hindered flow through the race, to a curved design and no dead ends, meaning cattle naturally follow each other around the system.”

Cattle enter the race and gather in a round crowd pen (above). A ratchet then pushes the cattle around the curved race before channelling them in to a single file chute. Once in the single file, the cattle are then moved through the race and around a bend with a gentle incline up to the stunning area.

“This is the bit that has made the biggest difference. Because animals can see a place to go and they can see other cattle in front of them, the animals move easily. The race is also long enough to take advantage of the animal’s natural following behaviour, so minimal human contact is needed.”

The curved race design keeps stress to a minimum which means meat quality can be maintained.

Upon arrival of the stunning area, cattle are shielded from the stunning box by a screen. “When Temple Grandin came and visited she suggested we make a few alterations. From her recommendations the ideas we had included adding brushes at the bottom of the door of the stun box, so any cattle trying to back up move forward once they feel the bristles of the brush on the back of their legs. The second alteration was to shield off any light coming from the stunning area which lowers stress for those animals waiting.”