A guide to managing fluke on your sheep farm

Not only is the weather changing, with warmer, wetter summers and milder winters, but the focus on mixed farming, longer grazing seasons and agri-environment schemes also add to the risk of fluke.

Combine this with the challenge of increasing drug resistance and the huge cost of infection and it is clear why sustainable fluke management needs to become more of a priority on farms.

See also: How farmer-vet ‘clubs’ are improving flock health

Fasciolosis is the disease caused by liver fluke infestation. It occurs when the liver fluke parasite, Fasciola hepatica, infects the liver of the sheep.

The immature parasites migrate into the liver after they are ingested when grazing, which causes damage to the structure and can lead to chronic disease and death.

Disease can also caused by adult flukes, which live in the bile duct before they are excreted.

It has a huge financial impact on farms through losses and abattoir condemnations.

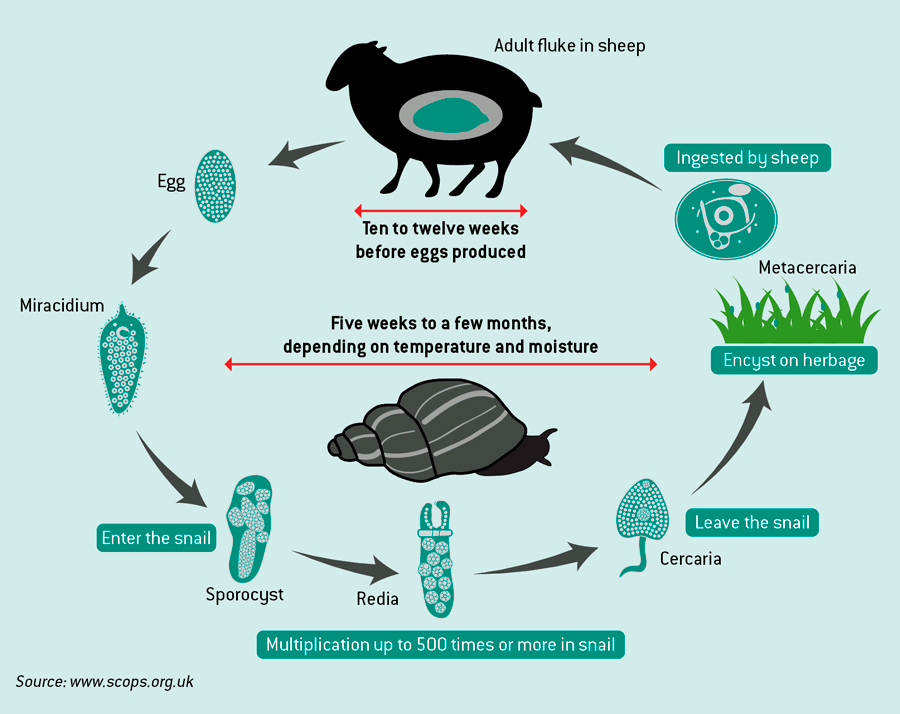

The lifecycle of fluke in sheep

There are three main clinical forms of liver fluke disease:

- Acute

- Subacute

- Chronic fasciolosis

Which form the sheep is infected by depends on the numbers of the parasite ingested, the period of time they are ingested for and the time of year.

All forms are serious, but sudden death is most often seen in animals with the acute form of the disease.

Diagnosis and treatment of fasciolosis in sheep |

|||||

|

Disease type |

Peak incidence |

Clinical signs |

Fluke numbers |

Faecal egg count (epg) |

Treatment |

|

Acute |

July to December |

Sudden death or dullness, anaemia, dyspnoea, ascites and abdominal pain. |

1,000+ mainly immature |

0 |

Triclabendazole. Treat all sheep and move to a lower risk (drier) pasture if possible or retreat after three weeks. Further deaths may occur post-treatment from liver damage incurred. |

|

Subacute |

October to January |

Rapid weight loss, anaemia, submandibular oedema and ascites in some cases. |

500-1,000 adults and immatures. |

<100 |

Treat with a fasciolicide active against mature and immature fluke. If sheep cannot be moved to lower risk pasture, retreat after five to eight weeks. |

|

Chronic |

January to April |

Progressive weight loss, anaemia, submandibular oedema, diarrhoea and ascites. |

200+ adults |

100+ |

All fasciolicides are active against the mature fluke involved in chronic disease. Treat and move to lower risk pasture. |

|

Note: This is just a guide. Treatments at farm level should be discussed with a vet or adviser. Source: Sustainable Control of Parasites in Sheep |

|||||

Fluke diagnostic options

A fluke infection can be diagnosed in various different ways while an animal is alive and dead.

There are invasive and non-invasive tests:

Invasive tests

- Post-mortem examination and meat inspection tests

- Blood sampling for liver enzymes

- Blood sampling for anti-fluke antibodies

Non-invasive tests

- Clinical signs

- Bulk tank milk tests – enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests

- Faecal egg counts

- Coproantigen test

Risk-assessing your farm

Warm and wet weather is particularly conducive to fluke risk and parasite survival because the vectors, snails, rapidly multiply and are infected by the larvae.

There are several options to try and reduce the risk of sheep or cattle consuming the parasite cysts, which stick to vegetation:

- Presence of water It is important to be aware of the risk of the presence of water, particularly with more agri-environment and flood prevention schemes around.

- Fencing Fencing stock away from particularly damp or boggy areas can reduce contact between animals and parasite cysts, which is particularly important from late August onwards.

- Drainage Be keeping ground well drained, you can reduce the habitat for the mud snails (the parasite’s host).

- Housing Bringing animals into buildings at particularly wet times of year can reduce the risk of infection. This is especially effective for cattle.

- Contamination mapping your farm Building up a picture of problem areas on the farm is important so that you can avoid grazing infested pastures.

- Quarantine Ensuring effective quarantine options are followed for bought in or returning sheep, goat or cattle are important. Quarantine requirements may vary between farms depending on the risk level, so farmers should develop a quarantine plan with a vet or adviser.

Resistance to flukicide

Triclabendazole (TCBZ) is the most widely used flukicide because it works on immature fluke. Like many widely used treatments, it has led to the development of resistance in several countries. While this is not confirmed in the UK, there have been reports of suspected resistance.

Failure of TCBZ treatment may be due to other factors, such as reinfection or inaccurate dosing

For more on liver fluke, including tackling resistance, fluke quarantine and treatment see the Scops website.

To prevent the development of resistance, rotational use of TCBZ, closantel or nitroxynil should be considered where flukicides are used strategically.

Opportunities to avoid the use of TCBZ should be exploited whenever alternative drugs will give satisfactory levels of control. For example, the use of closantel or nitroxynil three weeks post-housing, and/or treatment of chronic infections in the spring with an adulticide.*

Source: Sustainable Control of Parasites (Scops)

Case study: George Milne, Fife, Scotland

George Milne © Neil Ryder

Five years on from fluke disaster

Sheep farmer George Milne says he learned the hard way the importance of staying on top of fluke through faecal sampling when he experienced an outbreak in the winter of 2012-13.

Fluke had not previously been an issue on his farm near Fife on the east coast of Scotland – it was predominantly more of a problem for farmers to the west of him.

However, when buying in some fattening ewes, he got more than he bargained for, with a strain of triclabendazole-resistant fluke.

“It was a bad fluke year right across the country. We had losses and it wasn’t very pleasant,” says Mr Milne who has 250 breeding ewes and fortunately, thanks to the changes made, has experienced no losses to fluke since.

After realising that triclabendazole-based products weren’t working, Mr Milne says the first step was to find a product to “knock it on the head and then get the sheep into recovery mode”.

Reducing contamination became very important in the following year, so high-risk fields were not grazed and were cut instead, for hay or silage and only cleaner pastures were grazed.

Mr Milne is sure this helped to break the cycle of the fluke and then turned his attention to the most significant change – faecal sampling.

“What we are trying to do is keep very much on top of it,” he explains.

“We test mob dung to get it at early stages so fluke doesn’t build up on the farm.”

His strict approach sees samples tested, prior to any dosing, three or four times over winter.

Samples are sent to Scotland’s Rural College for testing and Mr Milne won’t treat for fluke unless results suggest they need to.

High-risk fields are now grazed, but Mr Milne tends to concentrate on these when taking samples.

“I try to use best practise on a practical basis. I know recommendations are to avoid particularly boggy and wet areas, but the reality here is, when you’re on the ground here in a wet year, everywhere is wet,” he says.

“I try and not overgraze, I try and keep sheep moving round, which helps with fluke and worms.”

Equally important, he believes, is the follow up test to see if the product has worked or whether resistance is present. He now primarily uses closantel-based treatments, but is careful to vary products to reduce selection pressure for resistance.

Given that the resistant fluke was brought on to the farm, it is no surprise that George is now “very careful” when it comes to quarantine. All purchased animals go into quarantine areas and fields, and are tested and treated before they join the flock.

While George has not seen any fluke flair ups since the awful winter five years ago, he knows he has to constantly be aware and test for it rather than become complacent.

He is clear that no farm is the same and both prevention best practice and suitable products will vary from farm to farm, but stresses that sampling is the key to staying on top of fluke and checking products you use have an effect.