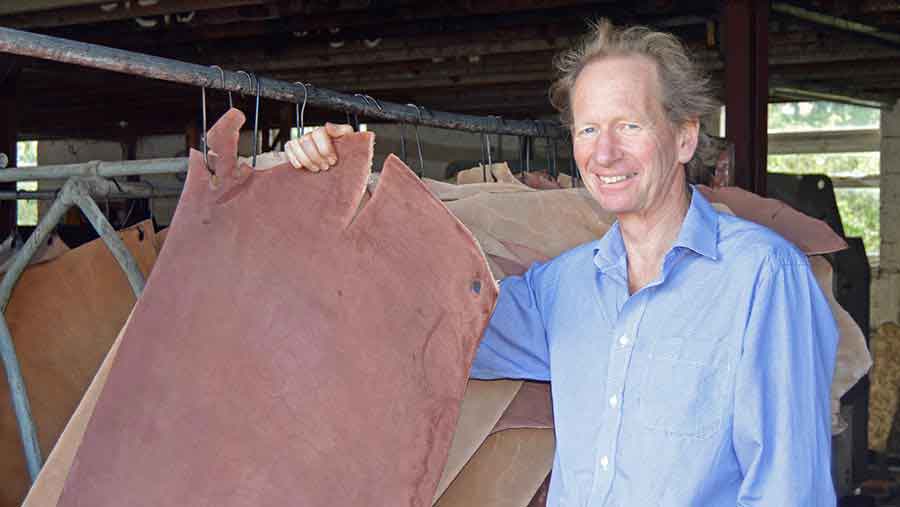

Photos: Turning a beef hide into leather

The industry talks more and more about what happens to farm produce when it leaves the gate, but what about the meat industry’s by-products?

“If you start with a bad hide, you finish with a bad hide. You want a well grown, healthy hide,” and that is why Andrew Parr, managing director of J & FJ Baker’s tannery, sources all of their beef hides locally.

Andrew has been working at the tannery for 38 years and it was previously run by his grandfather.

Tannery MD Andrew Parr with hides © Hayley Parrott

Based in Colyton, Devon, it is the only remaining traditional oak bark tannery in Britain and supplies top shoemakers and saddlers with its strong and durable leather.

There has been a tannery on the site since Roman times and J & FJ Baker has expanded the operation in recent years, all the while perfecting the art of tanning.

The raw materials

Oak bark will peel off easiest in the spring and summer as the sap is rising and most of the oak Andrew sources is from Wales and the Lake District.

He uses a combination of mature oak bark and the bark of coppice oak, preferring the latter as it contains more tannin.

Lots of other products can be used in tanning – minerals such as chrome and other woods such a mimosa and chestnut.

However, oak bark results in a really firm leather, which is what Andrew wants to produce because he supplies the high-end equestrian market and luxury shoemakers.

Hides are delivered weekly or fortnightly from West Country abattoirs and immediately begin the 12-month process of becoming leather

Since it is the only oak bark tannery in Britain, Baker’s has little competition for the bark, but Andrew has to pay a price to make it worthwhile for the bark strippers.

Once the bark arrives at the tannery, which gets through 12t every year, it will be kept for at least three years to ensure it has completely dried out so that the tannin will draw out easily.

He describes the process of extracting the tannin as “very much like making a cup of tea, but with cold water”. And it takes a bit longer – around a month in summer and nearer 6-8 weeks in the colder months.

It starts off as water and bark and finishes as a tan liquor and leftover bark, which is sent for compost.

Before the hide can be tanned, it has to be prepared and that means removing the hair and fat from it.

Hides are delivered weekly or fortnightly from West Country abattoirs and immediately begin the 12-month process of becoming leather.

The preserved hides have to be trimmed up before they are rehydrated and the process begins © Hayley Parrott

Andrew uses hides from big, continental beef animals. He doesn’t use dairy cow hides because the pregnancy and their pin bones both stretch the hide.

Hides arrive salted, to preserve them through dehydration, so the first stage is to trim the hide and rehydrate it for 24 hours before suspending it in a 2% lime solution.

The lime solution removes the hair from the hide © Hayley Parrott

This solution, over a fortnight, will work on the roots of the hair on the “grain side” of the hide to remove the hair and it will swell the fat, which can then be removed by a fleshing machine.

J & FJ Baker believes it is the last tannery to still use this process as most tanneries now use a lime solution with added sodium sulphide.

However, Andrew wants to use the gentlest possible process in order to leave the natural fibre structure of the hide as it is so that it’s as strong as leather as it is in nature.

Roger Tucker dehairing a calf hide by hand © Hayley Parrott

Tanning

Once the hide is dehaired and defleshed, it is called a “pelt”. Once a pelt is dry, which can take as little as a fortnight in summer, it is ready for the tanning pit, of which there are 72.

Each tanning pit will contain 12 or 24 hides. A new hide will go into a weaker tanning liquour, which is strengthened over time.

“It’s like cooking,” Andrew explains. “If you go straight on a high heat you just burn the outside but not the inside, whereas, if you build it up you get an even tan throughout”.

The hide will stay suspended in the tanning pits for around three months before moving to be layered in a pit with raw bark as well as the liquor.

The raw oak feeds the solution to keep the strength up and after nine months in a layered pit, the hide should be ready.

Some of the 72 tanning pits at J & FJ Baker © Hayley Parrott

However, it could stay in there forever and not spoil, a luxury that leather-making has over agriculture in that if the demand is not there, Andrew can just leave the hides until he needs them.

Drying

The drying shed at the tannery is heated all through the year. This is where hides will be hung once they have finished tanning and, at this point, their fate will be determined.

If the hide is to be used for equestrian materials, it will be dressed with oils (often fish) and greases, but if it is to be used for shoes, it will be rolled.

The rolling compresses the fibres, making it a harder piece of leather and increasing its water resistance. “We’re looking for wear for shoe leather and tensile strength for equestrian,” Andrew explains.

One of the more traditional rolling machines at the tannery © Hayley Parrott

Setting

The setting process involves pushing out any wrinkles and stretching the hide out. After it has been set once, it is oiled and then set again.

It is then in its “russet” condition, when treatment is complete, but it is not yet coloured. Some pieces of leather, such as harness backs for heavy horses, require extra dressing to strengthen them.

Different parts of the hide will have different uses. From one hide, cut up, you will get one shoulder piece, two belly pieces and two “butts” (the back pieces). Or if the two “butts” are not separated, this is called a “bend”.

On a hide there will be some areas where there are ripples, such as around the tops of the legs and the neck.

These parts of the leather, usually the shoulder cut, will often go to the leather goods industry, to become purses or flask holders, for example.

Russeted leather needs to go through a shaving machine in order to even out the thickness of the leather across the hide and be stained. One of the most traditional colours is the London colour.

Finishing

The final room before the leather leaves the tannery is called the brown shed. This is where a “courier” will finish off the leather, dressing it with dubbin.

Dubbin is a mixture of fish oil and mutton tallow and applied with a brush. For a polished finish, a piece of rounded glass is used on the grain.

James Tucker polishing a piece of leather © Hayley Parrott

Supply

A full grain, London colour butt would be sold at £145 and a pair of harness backs would be sold for £350.

Andrew pays £64 for a hide at the moment, which is £10 down on 18 months ago. However, it was £34 a hide 10 years ago, so this has changed a lot.

The dispatch room at F & FJ Baker is filled with brown postage tubes and barrels with exotic addresses on them – Dubai, Holland, Japan.

A lot of the leather is exported, which has seen a benefit from Brexit, but there is domestic demand too.

A glance at the online pricelist for some of the shoemakers Bakers supply reveals that a basic pair of shoes will set you back several thousands of pounds, which explains why the brogues Andrew wears to work are not made from his own leather.

He does have a pair made from his own leather though, which he has owned since 1982. They have been re-soled, but are still going strong. “I always wear those if I am travelling on an aeroplane,” Andrew says. “They’re my comfiest shoes”.