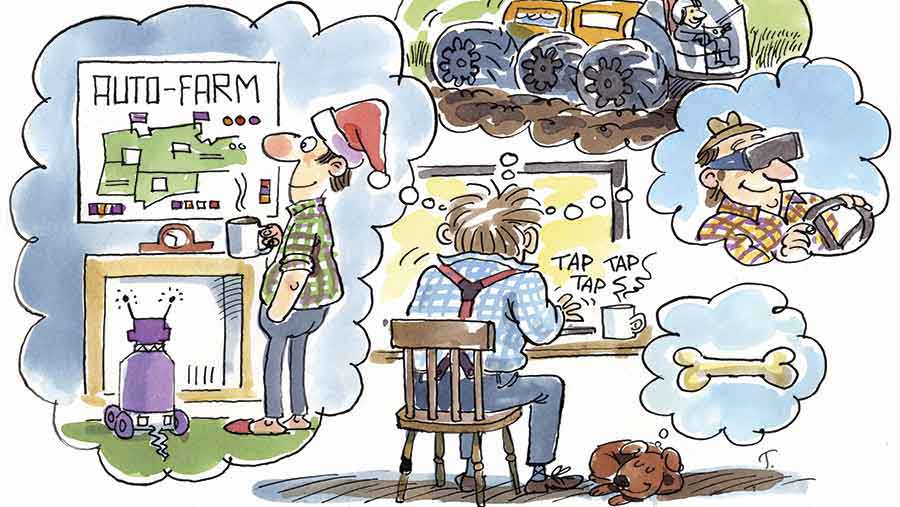

In cartoons: How a farmer’s day might look in the future

What will UK agriculture look like in a decade’s time? We take a look at how a farmer’s day might include cloud computing and wi-fi cows as the “internet of things” takes off.

It’s early morning in the post-Brexit world. The global population stands at eight billion, Toblerones are the size of an after-dinner mint, and Donald Trump is the supreme overlord of the universe.

The farmer of the future has just woken up. The date is 25 December 2026 and it’s far from a white Christmas – increasing global temperatures have seen to that.

In fact, it’s a rather typical December morning nowadays, following the US administration’s enthusiastic use of fossil fuels, which vastly accelerated global warming and led to a distortion of the seasons.

© Jake Tebbit

See also: Opinion: We need a technological revolution

However, things aren’t all bad. In years gone by, clothes were compulsory for the early milking, but gone are the days of actually needing to be in the parlour at 4am.

No, it’s stripy pyjamas and slippers for this agri-innovator. He fires up his tablet and opens his farm management app – the nerve centre of his business.

From here he controls an intricate network of sensors, telematics, hardware and software applications. They don’t just record millions of pieces of live data, but process them into useful, readable and crucially sharable open-source content into the cloud, for himself and others to use.

© Jake Tebbit

None of this would have been possible without the heavy government investment in super-fast, fibre optic broadband. The new 5G infrastructure has provided nationwide access for millions of remote, rural businesses, and has been essential in facilitating the third agricultural revolution.

The farmer of the future is all too aware of the value of his data, and there’s plenty of competition for this lucrative commodity.

Following the merger of all the world’s agro-chemical and seed corporations, Dubaysynsantchem has sought to monopolise the market – knowing harvest yields, animal performance and pesticide usage in advance is big business.

However, the market has been saturated by thousands of small tech start-ups which have been the driving force behind the agricultural revolution, bringing in technologies used in other industries like smartphones, robotics, fitness devices and global banking.

Wi-fi dairy cows

With a warmer climate, the herd remains at pasture later in the year, and bringing them in is an entirely automated process that begins inside the cow’s rumen.

The latest sensor is an all-in-one solution to a host of requirements, improving animal welfare and financial efficiencies by sending data to a wi-fi sub-station on farm and relayed to the farmer’s tablet every few minutes.

Acting as an accelerometer, the implant records each animal’s location and movements via GPS, providing our farmer with a tracker and helping him to adjust feed with more precision and identify lameness early.

© Jake Tebbit

The sensor also tracks each cow’s biological health, measuring stomach pH and temperature and allowing our future farmer to quickly identify illness and rectify a problem, as well as identifying when individuals are in heat.

The rumen monitor is so sensitive it can even detect the chewing motion of a cow’s jaw to notify our farmer when she is grazing. This allows him to monitor grazing history and take action against inefficient animals.

The cows come in from the field when they are ready – a pressure sensor detects when they begin to collect at the gate, automatically opening a solar-powered remote locking system for the farm’s web of fields.

See also: Sainsbury’s: Farming needs share of funding to up production

The rumen monitor remotely connects to the rotary parlour through bluetooth, sharing a myriad of data with the milking system’s smart AI (artificial intelligence) computer.

Upon entry, the herd is 3D-scanned and, along with other data, a ration is individually formulated.

Laser scanners then take over, identity the teats, and guide robotic suction cups; animals with tricky or twisted udders are logged in the system allowing the robot to adjust accordingly.

The on-board quality control system measures indicators such as cell count, protein, fat and lactose content, quickly notifying our farmer and his vet if there’s an issue.

As the milking gets under way and the farmer of the future is logging on to view his data he is being joined by hundreds of others who have a vested interest in what’s being recorded on the farm.

Data sharing and transparency

Under the 2021 extension to the Freedom of Information Act, anybody is allowed access to a full history of where their food has come from, doing away with supermarkets’ fake farm brands.

Since the policy’s introduction, consumer engagement and understanding of farming issues has improved, prompting new schemes to improve consumer engagement.

The farmer of the future is part of an initiative focusing on smart packaging that can be scanned, revealing a complete data-chain that enables total farm transparency.

See also: EU commissioner Phil Hogan calls for focus on farm science

It’s early days but initial results show improved animal welfare and nutritional standards and better public understanding.

Supermarkets too are checking day-to-day milk production figures to ensure a steady supply of the white stuff with the right constituents arrives on time.

Now that the large milk buyers can accurately forecast the supply of milk, thanks to the sharing of data, they can forward sell at home or across the globe, giving producers a welcome opportunity to lock-in to prices.

Zapping pesky problems

Halfway through a bowl of Future-O’s, a notification alerts our future farmer to a problem. Part of the farm’s intricate wireless sensor network (WSN) has detected the presence of insects – diamond back moths attracted to the warmer weather on his oilseed rape crop to be precise.

Using AI, these detectors monitor soil moisture and nutrient content, as well as the amount of water in the plants through subtle colour changes brought on by differing chlorophyll levels.

Heads of crops can also be scanned and counted, giving the future farmer a highly accurate estimate of yields well before harvest.

See also: GM warning shot over future trade deals

One of the sensor’s most innovative features is its ability to identify the presence of pests and distinguish between them using a combination of image recognition algorithms and acoustic detection.

After identifying the problem, these smart sensors possess the ability to direct a course of action against the infestation, enabling swift control and prevention.

The farm’s fleet of drone’s is called upon to deliver a pinpoint, highly localised spray of pesticides over the infested area. Not only does this save money on expensive chemicals, it also prevents any non-essential use, easing the impact on the environment.

Our future farmer’s four-engine quadcopters are perfect for this job. Connecting to the cloud, they have almost infinite on farm applications.

As well as herding livestock they can quickly identify lost or sick sheep whose value does not warrant expensive internal sensors, not to mention providing a bird’s-eye view for yield mapping, planting patterns and using infra-red sensors to detect the difference between healthy and stressed crops.

© Jake Tebbit

Being the traditionalist he is, the farmer of the future decides to check out the infestation for himself and hops in his tractor.

This 50hp, semi-autonomous vehicle is the perfect size for getting around the farm, but has the capability to add additional power units to quintuple engine size, adapting it to any job.

The machine is programmable through its central computer and features a minimalist holographic head up display (HUD) for satellite navigation, a speedometer and other readings.

Although renewables are in use across the farm, vast strides have been made in combustion engine efficiency, so electric and hydrogen powered tractors remain some time away.

The farmer’s fleet of autonomous vehicles are constantly at work in the fields under the guidance of GPS. Using the network of sensors, these precision vehicles independently plant seeds to within a few millimetres of their programmed location, and ensure they are harvested to the same accuracy.

Similar self-directed machines can detect unwelcome weed growth and deal with the problem through firing a low-powered infra-red laser, heating the plant cells and inhibiting their growth while leaving surrounding plants completely undamaged.

© Jake Tebbit

This reduces the use of herbicide saving costs, and where appropriate means the future farmers crops can be certified organic, commanding a premium price.

Arriving at the scene, the signs of infestation have been eradicated and the rape crop is pest free once again.

Climate-change technologies

Changes to global temperatures and the UK’s growing conditions have put pressure on bioscience to create more resilient plant varieties.

Genome editing has replaced transgenics as the consumer’s choice for engineering superior crops.

The process makes targeted changes to specific genes, thus promoting or removing certain characteristics to develop tailored plants for different environments.

As a result, the previously predicted yield plateau is being challenged and the impact of the unpredictable nature of the weather is being minimised by using flexible, adaptive crops.

With the weed threat neutralised, the farmer of the future can return to his command centre, safe in the knowledge that technology is keeping a watchful eye over his farm – letting him keep an eye over his turkey in the oven.