How tractors helped to win the war

Farm tractors took on a huge importance at the beginning of the First World War as Britain struggled to boost its home-grown food production.

The country had become heavily dependent on food imports and the German U-boat campaign aimed to sink ships bringing food and other essentials in order to starve the country into submission.

During 1917, the U-boats’ peak year, they destroyed 3.3m tonnes of British cargo ships.

See also: Classic Ford tractors rally at Blue Force demo

Ploughing more land to increase output became one of the government’s top priorities, but this was difficult while large numbers of men and horses were leaving the farms for the battlefields of Europe.

Tractors offered an effective way to boost production when farming still relied on almost one million horses, but Britain’s tractor industry was too small to meet the surge in demand.

Instead, the government ordered large numbers of tractors from American companies, such as International Harvester and Ford, with sufficient capacity to meet Britain’s needs.

Another job for tractors was haulage work for the Army. Horses still did most of the load-pulling on the battlefields, with steam traction engines handling heavier loads.

But steam power used large amounts of coal and water and tractors were increasingly preferred because they reduced the fuel and water supply problems, and tracklayers were also more effective in mud and shell holes.

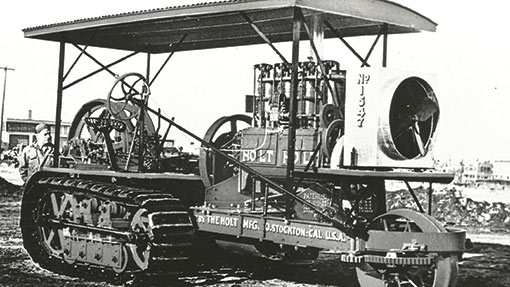

Easily the biggest contract to supply haulage tractors for the Army went to Holt in the USA, which supplied more than 1,000 tracklayers.

Tractors also played a major role in developing the world’s first battlefield tank, one of the biggest technical breakthroughs of the First World War. Tanks were important because they offered a solution to trench warfare that was causing huge losses on both sides.

Just one day’s fighting in the Battle of the Somme in 1916 cost 57,000 British casualties, including almost 20,000 killed, most of them victims of machinegun fire during a futile attack on enemy trenches.

Tanks on tracks could drive through barbed wire entanglements protecting enemy trenches and then over the trenches, destroying machineguns as they went. Foot soldiers walking behind the tanks gained some shelter from enemy bullets and reached the enemy trenches through gaps in the barbed wire left by the tanks.

Tractors become tanks

The earliest ancestor of the tank was a tractor built by Richard Hornsby & Sons of Grantham, Lincolnshire. The company made farm machinery and steam traction engines and in 1896 it demonstrated one of the first British-built tractors.

Powered by a single-cylinder engine, it was designed for haulage and powering a belt drive for threshing and was advertised in 16, 20, 25 and 32hp versions.

It became the first tractor to win a Royal Show silver medal, but it was years ahead of its time. It attracted only one UK customer, a Surrey landowner who was the first person in Britain – and probably the first in Europe – to buy a tractor. About four Hornsbys were exported to Australia.

Although farmers were wary of the Hornsby, the Army decided tractors might be useful for haulage. It arranged a competition in 1904 for the best load-pulling tractor, offering a £1,000 prize – a generous amount then – plus the prospect of future orders for the winner.

Hornsby entered a special 70hp version of its tractor, which won the competition easily and was the only entry to complete the trial. The Army then lost interest and the future orders never arrived.

Meanwhile David Roberts, Hornsby’s managing director, had developed a set of tracks fitted on an experimental 20hp tractor. As well as better traction and soft ground capability, tracks also allowed the tractor to cross ditches or trenches up to about 1.4m wide. Army officials watching a demonstration in 1906 were impressed.

New fighting machine

A bigger, more powerful prototype was purchased by the Army for evaluation and development. This was the machine that sparked the idea that, besides haulage work, a tracked vehicle could carry a gun and become a new type of fighting machine.

The Army’s interest probably raised hopes at Hornsby that big contracts would follow, but they were disappointed because the Army lost interest and abandoned the test programme.

Objections are said to have included the noise of the un-silenced engine frightening Army horses, and some soldiers complained about the smell of the exhaust fumes.

A lasting result of the test programme was that soldiers referred to the tractor as “the caterpillar”, and this is believed to be why the name was chosen when the Caterpillar tractor company was formed in 1925.

One of the companies merging to form Caterpillar was Holt, which had previously bought Hornsby track patents.

Later, as wartime casualty figures mounted, Army officials remembered the tracklayer and its ability to drive over trenches, but Hornsby had abandoned its tractor and track development work. When the Army belatedly decided to restart the development programme they turned to American companies for help with an evaluation programme that included Holt, Bullock Creeping Grip and Killen-Strait crawler tractors.

A first batch of 42 Mark 1 tanks was ready for action in France in September 1916. Each tank carried eight men, weighed 27t and was powered by a 105hp Daimler engine, and the tracks could cross a 3m wide trench.

There were, inevitably, design faults, including poor reliability and the slow forward speed, but the ability to break through the trench system was a significant contribution to winning the war and provided a huge morale boost for the soldiers and for their families in Britain.