Farmer’s tribute on 80th anniversary of wartime air crash

© MAG/Johann Tasker

© MAG/Johann Tasker A Suffolk farmer has unveiled a memorial to the American aircrew of a World War Two bomber which crashed in one of his fields – and welcomed their families to his farm.

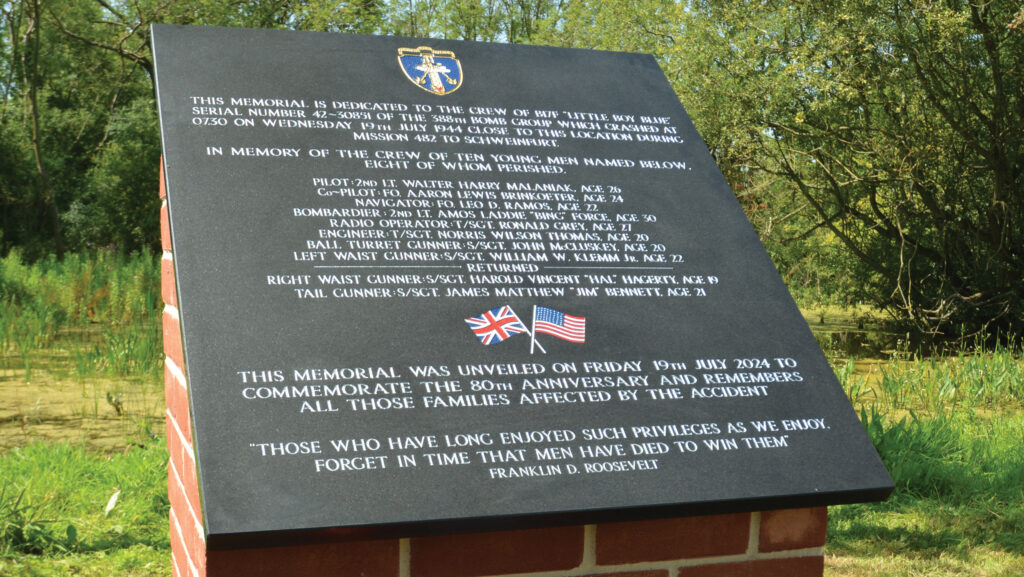

Stephen Honeywood hosted a memorial service for the crew of the B-17 Flying Fortress “Little Boy Blue”, which went down on 19 July 1944 just outside the village of Thurston, near Bury St Edmunds.

Relatives of the aircrew and local villagers gathered for the service – held in the corner of an oat field on the 80th anniversary of the crash. Only two of the 10 aircrew survived the fatal accident.

Many of the crew were in their late teens or early 20s. Mr Honeywood said: “We were aware that this was the 80th year and thought perhaps we ought to do something to commemorate the young lads who were lost.”

See more: Video – 90 and Counting: Somerset sheep farmer John Small

© Roger Freeman Collection

Tracing the families

He also set about trying to track down the families and let them know.

He started by looking for the relatives of the two survivors: 19-year-old waist gunner Harold ‘Hal’ Hagerty and 21-year-old tail gunner James Matthew ‘Jim’ Bennett.

“Their families were the easiest to trace because they survived,” said Mr Honeywood.

“Once we had found them, everything snow-balled and we managed to trace families of the other crew members too. We’re delighted so many wanted to join us.”

Hal Hagerty’s son Patrick Hagerty made his way from Oregon to attend the memorial service.

Speaking from the lectern, he held aloft the ripcord and a remnant of the parachute which saved his father’s life.

Mr Hagerty told the congregation: “The day was no different than any of the previous 67 missions. [The plane] was fuelled up.

“Five 500lb bombs in the bomb bay and thousands of rounds of 50 calibre machine gun ammunition. Ready for war.”

Fatal mission

Little Boy Blue took off to join 1,200 other bombers to hit Schweinfurt, Germany. But engine trouble meant she soon fell behind.

The problem was rectified and the bomber was at full power and continued the mission.

“Having fallen behind, she was overtaken by the next group of bombers [and] a mid-air collision occurred,” said Mr Hagerty.

“The propellers of another plane cut through the fuselage of Little Boy Blue – just adjacent to where my father was sitting.

“He heard the sound of metal grinding and felt the plywood floor explode into his face.

“He grabbed the handle of his unattached parachute and found himself tumbling in blue sky all alone. He was able to attach his parachute and pull the rip cord.”

Stephen Honeywood, centre, with Patrick Hagerty, left and Frank McCluskey, right © MAG/Johann Tasker

Missing in action

The collision was at 15,000 feet. The parachute opened at 2,500 feet. Hal Hagerty saw two other chutes. One was the other survivor, Jim Bennett. The other was co-pilot Aaron Brinkoeter, who landed in the burning wreckage.

Mr Brinkoeter’s body was never found. Neither were pilot Walter Malaniak nor radio operator Ronald Grey. All three have since been commemorated on the Wall of the Missing at Cambridge American Cemetery.

Bishop of Dunwich Mike Harrison, who led the memorial service, said it was an important event for the families of those who had died, some of whom had long sought closure – as well as for the local community.

It was an opportunity to grieve and to honour the sacrifice of those who served, said Bishop Mike. “There is a special bond which is forged through war – and from going through such extremities together – and that was visible today.”

‘There was an almighty crash and bang’

© MAG/Johann Tasker

Local villager Brian Cracknell remembers seeing the B-17 Flying Fortress come down as a schoolboy in July 1944.

“It was a sunny morning and there was an almighty crash and bang and the windows all shook,” he says. “I woke up and looked out the window to see the tail end of an aeroplane spinning over and over.”

Rushing outside, Mr Cracknell and his friends managed to locate the tail section of the plane in a field. There was nobody in it, he says. the main fuselage landed about a quarter of a mile away – the other side of a railway line.

“We weren’t allowed near the crash site, so we stood by the side of the road. There were sections of parachute and a lot of debris. It has been something that has been a memory all my life.”

Lost airman’s dog tag recovered

Volunteers led by Cotswold Archaeology recovered the dog tag belonging to co-pilot Aaron Brinkoeter last September – during a crash-site excavation commissioned by the American government.

The recovery effort to find the three aircrew still listed as “missing in action” sought to finally locate and repatriate their remains – and the hope of bringing some closure to their families.

The Cotswold Archaeology team included UK military veterans from Operation Nightingale, which helps the recovery of wounded, injured and sick service personnel by getting them involved in archaeological investigations.

They worked alongside serving US military personnel, members of the Suffolk Archaeology Group and Cranfield University’s Recovery and Identification of Conflict Casualties (CRICC) team.

Local metal detectorist Clive Smither discovered the dog tag on 12 September – on his first day working with the dig. It was found on 12 September – which would have been Mr Brinkoeter’s birthday.

Lasting legacy echoes down the years

More than 200 UK airfields were used by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during the Second World War – many of them built on East Anglia farmland.

Known locally as the “friendly invasion”, up to 500,000 American airmen and women were based in the UK during 1944 – playing a key role in the run-up to D-Day and eventual victory against Nazi Germany.

Each airfield housed about 2,500 American personnel – often far outnumbering the local population. Their impact was huge – bringing with them big band music, chewing gum, nylon stockings and Coca-Cola to war-torn Britain.

Today, most of the airfields have long since been returned to farmland – with local farmers often hosting American families visiting the UK to see where their relatives served during the war.