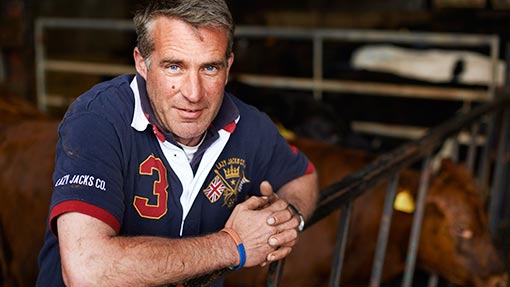

Dealing with depression: Farmer speaks out

Experts say depression is widespread in farming, but it’s rarely talked about. Instead, it quietly and often invisibly wrecks lives. Farm manager James Drury tells Tim Relf about his experiences – and shares his advice – in a bid to help break the stigma.

It’s a warm spring day and James Drury is off to help one of the Somerset farmers worst hit by flooding drill spring barley.

Like everyone who watched it, the Bicton College farm manager was moved by news footage of the deluge. He immediately offered to help those affected get their crops in the ground – and has vowed to return at harvest if it will make a difference.

“What a brave chap,” he says of the guy he will be assisting. “Not just to have gone through what he has, but to have accepted the offers of help. Some farmers wouldn’t do that.”

Depression is an illness

James is the first to admit it’s something he wouldn’t have been capable of doing even as recently as last autumn. He has experienced intense bouts of depression over recent years, which at points have left him unable to work, seen him estranged from his family and friends, and even led him to consider taking his own life.

“Depression is an illness, but one that people sometimes can’t see. If I’d broken my leg and you had met me, you would have known exactly what was wrong with me – but if you had met me a few years ago you wouldn’t have.

In many ways I wish I’d had a ‘physical’ illness instead – even, God forbid, a serious one like cancer – because more people might have understood what I was going through.”

James’ depression has come in peaks and troughs, but he traces its origins to 2008-09 when the farm he was managing in Scotland was put on the market.

It was a job he loved so was “gutted” and, although he secured employment elsewhere, he soon felt it wasn’t a great move. By 2011, an unhappy work and personal life really began to take their toll.

Effects of depression

“I was working, but not coping. I lost my ability to make a decision, I simply didn’t have the energy. I couldn’t concentrate on anything, not even a conversation. I’d spend hours and hours in my truck, driving round, terrified. I was an emotional wreck and avoided everybody and everything, even my family. You get to a point where you simply can’t function. I became a person I didn’t know. I basically had no desire to carry on.”

Crisis point

In September 2011 – unsure where to turn – he found himself facing a stark choice: run away or ring the Samaritans. “I thought they’d be my saviour. We talked for 45 minutes, but I thought at the end of that exchange: That’s solved nothing.”

The following year, still deeply unhappy, constantly on edge and unable to understand what was happening to him, he went to see a doctor. “She said I was depressed and signed me off work. I began taking antidepressants and thought everything was going to change overnight. It didn’t.”

James does not know to this day what, if anything, specifically “triggered” what he describes as “the ultimate downward spiral” in 2012, by which time he was living with his wife and two children in Devon.

He hired a car and decided to go and stay with his parents in Kent, but instead “went Awol”, driving out on to Exmoor, switching his phone off and spending 24 hours there in the car. He was wrestling with a decision: to carry on, or not to.

“I needed that time on my own to come to terms with what was happening and make a decision on my own. Eventually, I decided I wanted to get better.”

When he came down off the moor, his phone was full of messages, including from Cullompton Police, as he’d been reported missing. “I went to the station in a right state and made it clear that I wasn’t leaving until the help I thought I needed was forthcoming.”

Counselling

They took him to A&E, he was assessed by specialists and promised a course of intensive counselling with a trained mental health professional. They were eight sessions that, according to James, changed his life.

“I’d had years of bottling up problems and not sharing them with anyone, but I began to understand the value of opening up and talking to people.

“Talking was the biggest healer. It helped me compartmentalise all my various questions and problems, tackle them one by one, rather than me being left with this muddled sense of being overwhelmed.

“It’s a strange analogy, but imagine the biggest spot you ever had as a teenager – it gets bigger and redder and more sore, then eventually it pops and all the crap comes out. Once I’d taken that step, I was on the road to recovering.”

Coping strategies

Counselling also taught him coping mechanisms. “Depression is an illness you have to manage by understanding how it affects you, how you can manage the types of things that can send you back to that place, and by recognising what the signs of it coming back might be.

“If it rained and I couldn’t get out combining, that used to eat me up. I was always worried about people looking at me, and saying ‘he’s not coping’ so I’d do stupid things like working until 3am. I don’t let myself get totally consumed by work anymore. I take more of a c’est la vie attitude; I try to keep things in perspective.

“It’s about getting some fun back in your life, and you have to be quite disciplined in that respect. It’s amazing how much better taking a break or even just taking the dog out for a 20-minute walk can make you feel.

“It’s important to make time to be with friends and to talk about things other than work. I went to the theatre to see Mamma Mia recently. That was the type of thing I enjoyed doing before I was ill. Two years ago, I’d have found any excuse in the world not to go. But I absolutely loved it.”

James is also sure that without the counselling he would not have got a job at the highly respected Devon agricultural college, Bicton, which he started last November.

Having such great support from the college’s management team has made him conscious of how isolated and unsupported many farmers can feel, especially concerning mental health issues.

“There’s still a huge gap in understanding in the workplace,” he says. “Just look at how some people describe it – they still use expressions like ‘gone cuckoo’.

How many farms have an occupational health policy? How many employees could go to the boss and describe how they’re feeling? It’s partly because of the small nature of businesses, but there’s a culture of never opening up.”

Support

James is keen to support others facing a similar situation. “While it still feels very recent and I do find it very painful to talk about, I really want to help other people who are experiencing depression. Once, I wouldn’t share anything with anyone, but I’m prepared to speak about my experiences now.”

As well as hoping to help rural support groups such as the Farming Community Network, he’s keen to raise awareness in whatever ways he can. “Nobody should have to face this alone.”

He wonders if there’s a benefit in setting up a new support network, specifically aimed at farmers in the South West. Maybe enlisting the help of a high-profile figure in farming to help him spread the message? Giving talks at agricultural shows and events?

“The Samaritans do some incredible work, but they couldn’t help me because they didn’t understand the specific issues I was facing. If I could have spoken to a farmer, they’d have understood what it was like to have potato fields like the Somme and that would have helped.

“They wouldn’t have been able to solve it, but having someone at the end of the phone who at least appreciated the impact that things such as weather can have on you would have been a breath of fresh air and really made a difference.

“I’d urge anyone feeling like I did to talk to someone who they feel they can confide in. It might be your wife or husband, but it could be anyone. Ask them to help you get through it.

“Similarly, if you think a family member has depression, gently and gradually push them in the right direction by encouraging them to see their GP or by getting them to talk about it. If I’d admitted I needed help earlier, I wouldn’t have got into the mess I did. Don’t let yourself get to the place where you can’t be helped. If you get to the point where you recognise you need some help, you’ve turned a corner.”

One question James cannot ultimately answer is what “caused” his depression. “I wish I could put my finger on it, but I can’t. It was a combination of many things that got gradually worse and snowballed.

No shame

“It’s awful to think that you can get to the stage where you think people will be better off without you. The only reason I didn’t do the most stupid thing was because of my children. I was on a knife edge, but I got the help I needed eventually and that began to make sense of everything.

“Of course I’m sorry for what happened, but I don’t feel any shame in it. I did the best I could, but the truth is I wasn’t able to manage it. I’m content with myself about that.”

Nowadays, although he still carries some “deep emotional wounds” and his illness has taken its toll on his family life and friendships, he has found some happiness again.

“My mum once said that in every photo of me for years, I look troubled or unhappy. I had lost the enjoyment in life, but I’ve found it again now. There is light at the end of that long, black tunnel.”

James enjoys riding, reading, spending time with friends and loves his job at Bicton – being involved in a progressive, ever-evolving college farm. “Every day is different and exciting.

“In my own small way, I wanted to give something back to the industry I love. If I can help foster young people’s interest in agriculture and they can learn a little from me, then I’m determined to.

“I’ve also always said I’ll win a Farmers Weekly Award one day — and one day I will.”

The symptoms of depression vary widely, but if you experience some of these symptoms for most of the day, every day for more than two weeks, you should seek help from your GP.

Psychological symptoms include:

- Continuous low mood or sadness

- Feeling hopeless and helpless

- Having low self-esteem

- Feeling tearful

- Feeling guilt-ridden

- Feeling irritable and intolerant of others

- Having no motivation or interest in things

- Finding it difficult to make decisions

- Not getting enjoyment out of life

- Feeling anxious or worried

- Having suicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming yourself.

Physical symptoms include:

- Change in appetite or weight (usually decreased, but sometimes increased)

- Loss of libido

- Disturbed/altered sleep pattern.

Social symptoms include:

- Not doing well at work

- Taking part in fewer social activities and avoiding contact with friends

- Neglecting your hobbies and interests

- Having difficulties in your home and family life.

Concerned?

If someone close to you is showing signs of depression, you can:

- Listen to their concerns. Saying “pull yourself together” is not helpful.

- Be supportive. Although you might not be able to provide direct help, offer reassurance.

- Respect their confidence.

- Encourage them to seek professional help (offer to go with them).

- Find out more about stress and depression and take advice yourself on how to help.

- You can advise their GP if you are concerned about their health (even though the GP cannot discuss their patient with you).

Source: NHS

- The Farming Community Network 0845 367 9990

- Royal Agricultural Benevolent Institution 0300 303 7373

- Gatepost for RSABI 0300 111 4166

- Mind Infoline 0300 123 3393

- YANA (You Are Not Alone) 0300 323 0400

- Samaritans 0845 790 9090

- Survivors of Bereavement by Suicide 0300 111 5065

Charlie Bransen, Surrey

‘I asked my wife to hide the guns’

As someone who’s experienced clinical depression for many years I think it stems from an inability to shut off, to filter, to screen all the information received by our senses, and to deal with it mentally.

Sometimes there’s simply so much stuff coming in. It makes you feel like you can’t cope, you can cry for no reason in embarrassing circumstances, feel anger, despair, hopelessness, a lack of motivation, drive and energy.

I have been in such depths of despair that, in a lucid moment, I asked my wife to hide my guns. Had I not done that, I know I would not be here now.

Farmers, particularly, are at risk because so much of life is beyond their control – such as the weather, machinery breakdowns and consequently finances.

Add in all the other variables like family pressures, age and fitness, and our brains, when fit, can cope up to a point. But when you’re run-down, lonely, stressed, sometimes you just want peace in your head, to stop the “noise”.

Tell people close to you. Don’t be ashamed. It is such a common affliction you’ll find others have suffered or are suffering – sometimes much closer to home than you think possible.

Once you’ve admitted the need for some kind of help, then things are a little easier.

See the doctor. We’re all against drugs generally, but there are contradictions here in that we’re more than happy to use the best modern science has to offer to grow our crops.

Getting prescribed antidepressants by your doctor can work for some people. It can help you regain a little composure so you can start to develop strategies to cope. In the past, seeing a doctor and taking the medication he recommended has definitely enabled me to function again. It might be just a course for, say, six months or a year, until one is back up to speed. My doctor has reassured me that the particular drugs I’ve taken are not addictive.

Don’t forget, there is a benefit to coming through all this alive: one is more understanding, more caring, one appreciates all those little things in life and that life is indeed precious.