Columnist AG Street remembered by his granddaughter

AG Street was one of the foremost agricultural commentators of his generation and a longstanding Farmers Weekly columnist.

To mark the 50th anniversary of his death, his granddaughter Miranda McCormick gives a unique insight into the life of this unique countryman.

© Frank Hudson/Associated Newspapers/Rex/Shutterstock

“Most of those who are writing about the present agricultural depression are suggesting that somebody or other should do something for agriculture, never that agriculture should do something for itself… A generation of farmers must arise who can get a living in spite of any government rather than with the aid of any government intervention.”

Thus began the first article ever written by my maternal grandfather, the Wiltshire farmer/author/broadcaster Arthur George (AG) Street, published in the Daily Mail on November 22, 1929, entitled “Handicaps on Agriculture”.

These sentences might have been written today, particularly in light of the result of the EU referendum.

His name would have become familiar to readers of the Farmers Weekly as early as 1935, when he began his weekly column; apart from the very occasional gap, such as the beginning of the Second World War, he continued to write it until his death in 1966.

Manitoba

Born in 1892, my grandfather Street was the youngest son of a tenant farmer on the Pembroke Estate in Wilton. Having left school at the age of 15, he worked for his father at Ditchampton Farm until 1911.

They quarrelled bitterly and he consequently sailed to Canada and became a farm-hand in Manitoba, breaking the virgin prairies, work he later considered to have been a privilege, since it had allowed him to “make his mark” upon the earth.

Forever after, he referred to ploughing as the “king” of agricultural jobs.

My grandfather was born with his feet pointing in the wrong direction, and spent his early childhood in irons to correct the condition.

Although fully mobile by the time the Great War broke out, he felt deeply humiliated on being rejected from military service by both the Canadian and British armies on account of his feet.

So instead, he found himself working again at Ditchampton Farm, taking over the tenancy in 1918 after his father’s death.

At the end of the First World War, there was a brief spell during which farmers prospered, but it was not long before a deep agricultural depression set in.

Grandfather Street was very much a believer in self-help and not afraid to make radical decisions; to avoid bankruptcy he ploughed up all his arable fields for pasture, and went in exclusively for dairy farming, so creating a wealth of fertile soil for when it needed to be ploughed up again at the beginning of the Second World War.

Another of his radical decisions was to adopt an outdoor mobile milking system known as the “bail”, meaning cows could be milked in the field in which they had been grazing, then the bail moved on to the next field.

© Associated Newspapers/Rex/Shutterstock

As the agricultural recession deepened, however, bankruptcy still beckoned. Never one to admit defeat, my grandfather unashamedly became a milk retailer as well as producer, donning a white coat and selling his milk to housewives all round Wilton and Salisbury from a van with “AG Street – Open Air Milking” printed on the side.

These were the circumstances in which my grandfather was living when he wrote that life-changing Daily Mail article.

Already frustrated by being confined indoors recovering from a bout of flu, he was so infuriated by an earlier article about farming he had read in its pages that he felt compelled to write this as a counter-blast, for which he was paid three guineas – a great deal of money in those days.

Realising he was on to a good thing, he continued to write articles, particularly for the Salisbury Times. One of these caught the eye of a respected local novelist, Edith Olivier.

A great supporter of budding writers, she arrived unexpectedly at Ditchampton Farm one day, waving the article in question, insisting that grandfather Street should write a book.

BBC

This was the genesis of Farmer’s Glory, his first, best-selling book. He went on to write many more articles, soon attracting the attention of the BBC, who encouraged him to embark on his third career, broadcasting.

By 1939, when the Second World War broke out, his voice was already well known on the airwaves.

The first effect of war on country-dwellers was the housing of evacuees: in the Streets’ case, three, seven-year-old girls from Portsmouth. There then followed a succession of billetees, including many military personnel (Wilton House became the HQ of Southern Command in the summer of 1940).

For farmers, the second effect was the call-up of many of their staff, with family members having to take their place. My mother Pamela, by then 18, became – in her own words – a “glorified land-girl-cum-secretary”, learning to drive a tractor and type for her father.

Grandfather Street sent away his hunter, Jorrocks, to be trained for the harness. At first he had to abandon much of his writing in order to concentrate on farm work; fortunately his foreman returned after only a few months, since the authorities considered the latter’s civilian job more important to the war effort.

On May 15, 1940, after Holland and Belgium had been overrun by the Germans, Anthony Eden put out a call for Local Defence Volunteers – later to become known as the Home Guard.

On May 15, 1940, after Holland and Belgium had been overrun by the Germans, Anthony Eden put out a call for Local Defence Volunteers – later to become known as the Home Guard.

My grandfather was the first round at Wilton Police Station to put his name down; finally, in middle age, he found his services were not rejected by the military, and he went on to take his duties very seriously, soon becoming a platoon commander.

He went on to write a semi-autobiographical description of his Home Guard experiences in an amusing little book, From Dusk till Dawn, first published in 1943; it has been suggested that this might even have been the original inspiration behind the television series, Dad’s Army.

Meanwhile my grandfather was commissioned by the BBC to report on the state of British agriculture in all parts of the British Isles. One example was a visit to a flax mill in Bridport, Dorset, in March 1941. The government was encouraging farmers to grow flax, and he was indeed about to sow his first crop.

In his broadcast (later published in his book Hitler’s Whistle), he explained that flax as a farming crop had all but died out in the British Isles, being readily obtainable from overseas, but now it was in demand again for military use such as canvas, tents and parachutes.

He found, in the Bridport town guide, an edict from King John to the Sheriffs of Somerset and Dorset to “cause to be made at Bridport, night and day, as many ropes for ships, both large and small, and as many cable as you can, and twisted yarns for cordage for ballistae”, and was thus able to make an analogy between military needs in 1213 and 1941, concluding: “…which is yet another case of history repeating itself.

The sails of Nelson’s Victory were made in the West Country from English-grown flax: and as past victories depended, so also will our coming victory in this war depend, largely on the produce grown on the land of our own country.”

People of my generation and older remember my grandfather mainly from his regular performances on Any Questions? during the 1950s and early 60s, under the chairmanship of Freddie Grisewood.

An old recording of a programme, broadcast in 1992 to mark my grandfather’s centenary, includes several clips from these.

They demonstrate his popularity as a panellist, coming across as the big, bluff, independent Wiltshire farmer who enjoyed an argument, skilled at knowing how to “play” an audience.

He seemed never happier than when pulling a politician down to size with a dose of countryman’s common sense. Here is his response to a question about whether or not MPs deserved an increase in salary:

“You can see in the local paper any number of advertisements for farm-hands, plumbers, typists, cleaners, washers-up and so forth, but have you ever seen an advertisement for a politician? Politicians are surplus to requirements.

There are at least 10 times as many would-be politicians than seats in the Houses of Parliament, and when there is a surplus of something, the price should go down [pause for laughter]. And the deposit should go up [again pause for laughter].

For example, at the moment there’s a surplus of milk, and the price has gone down. But while you can still make useful things from a surplus of milk, such as butter and cheese, if any of you can think of a single thing you can make from a would-be politician, I’d like to know [howls of laughter]!”

I believe that my grandfather’s childhood infirmity influenced his adult character considerably. Unable to get about, he developed a forceful, stubborn personality, having to yell to attract attention.

It engendered in him both a strong desire for independence and a fiercely competitive streak – he was determined to prove himself more than the equal of any of his siblings.

Haggling

Nothing in later life was going to defeat him and, as a young man – now well able to walk and ride – he took up both country sports and other games such as golf, tennis and bridge. He was also blessed with huge stamina.

He relished haggling for the best deal with cattle dealers in Salisbury market and later in life with his BBC producers over increases in his fees. What drove him most was his love of the land.

A constant theme in his many books (in total 34 under his own name plus one under a pseudonym) is the belief that a countryman’s first duty is to serve the land. However much his wartime broadcasts and writings were written for propaganda purposes, the sentiment behind them was sincere.

© Associated Newspapers/Rex/Shutterstock

Those who worked for him considered him a firm but fair employer. He frequently argued that farmworkers should be paid a fair wage in comparison to their urban counterparts; he also advocated the modernisation of tied cottages, including proper indoor sanitation and hot water.

He was instrumental in the phasing out and eventual disappearance of the four bushel sack, arguing that this resulted in serious back injuries. Another of his campaigns was for the polling of cattle to prevent injury both to them and to farmworkers – an idea popular in its time, although it never became compulsory.

My grandfather was also a devoted family man. My mother (who went on to become a prolific author in later life) once wrote: “I suppose we must always have been an emotional and rather tender-hearted family.”

As an example of this, she cited an occasion in 1937 after her father had been on a lecture tour of Canada and the Mid-West.

So eager was he to be reunited with his family that when his ship docked, he found a way to disembark that evening rather than the following morning with all the other passengers.

My mother remembered being driven to collect him from Southampton Docks in an early mock blackout: “In the all-pervading gloom, I remember my father, all alone, bolting down the gang-plank like a large hunter desperately anxious to get out of its horse-box.”

Although there was no doubt who “ruled the roost” at Ditchampton Farm, my grandfather clearly adored and respected my grandmother Street, often quietly taking her advice.

He and my mother (their only child) became particularly close as a result of their joint riding activities. One thing on which he insisted, however, was having all his “womenfolk” under his roof before he retired to bed – he later wrote that this was the “peasant” in him.

My mother recorded his fury with her at one point during the war when she went to a party, having ordered a taxi to take her home.

Unfortunately the taxi failed to arrive and, unwilling to telephone her parents in case they were asleep, she had been relying on some American soldiers to give her a lift back.

When the party eventually broke up, she found both her parents waiting on the doorstep, having used some of their precious petrol ration; apparently grandfather Street refused to speak to her for an entire week.

My parents (who had met on the summer of 1940) married in July 1945, only a few months after the end of the war. My father, like so many young men returning to “Civvy Street”, found it hard to find suitable employment.

Eventually he was given a job in a stockbroking firm in the City, but found it too akin to being cooped up in a POW camp (he had been a prisoner of war for over three years).

He hankered after the rural life, and asked his new father-in-in-law whether it might be possible for a complete novice such as himself to become a farmer.

Grandfather Street negotiated the purchase of a nearby farm for him, and holding his hand for the first year; fortunately my father proved an apt pupil and the farm thrived.

The same could not be said of my father’s health; in the mid-1950s he was diagnosed with severe angina, and told to take a break from farming for several months.

Having made arrangements for the running of the farm in his absence, he departed with my mother for a long cruise to South Africa, leaving me – then aged five – in the care of my grandparents Street.

It was during this period that grandfather Street and I forged a particularly special bond. He would take me round the farm in his Land Rover, introducing me to all his farm staff.

He was tickled pink to hear one of them comment that I was a “chip off the old block”, and from then on gave me the nickname “Chip”, insisting that I should call him “Chap” in return.

Fishing

He introduced me to all manner of exciting activities – fishing for minnows with a jam-jar in the River Wylye, training gun dogs and, best of all, flying a box-kite on the end of a fishing rod and line.

Miranda McCormick

All this went into one of his later novels, Bobby Bocker, which he dedicated to me.

Sadly it was not particularly well received, being considered somewhat mawkish and clearly a departure from the kind of subject his readers had come to expect.

What would my grandfather Street have thought of farming today? In the early post-war years he was very much an advocate of free trade: no tariffs, no subsidies.

He hated what he called “hand-outs” to farmers (with the exception of hill farmers in more remote parts of UK, for whom he acknowledged life could, at times, be truly harsh).

He believed that subsidies only served to prop up bad farmers, while tempting good farmers to become lazy.

An obvious “Brexiteer”, one might say; yet he was shrewd when it came to financial matters, and would have been well aware of the negative impact that leaving the EU might have on today’s farming community.

What a pity he is no longer with us to debate the case on Any Questions? He would certainly have livened up the discussion.

More reading

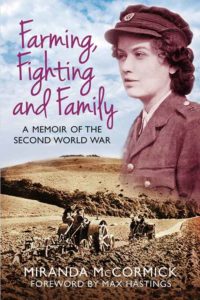

In Farming Fighting and Family: A Memoir of the Second World War, with a Foreword by Max Hastings, Miranda McCormick uses previously unpublished letters and diaries to weave together the very differing wartime experiences of her parents and grandparents into a single chronological narrative.

This intimate and compelling account of love, duty and separation during a time of national adversity is available from www.thehistorypress.co.uk and all good bookshops.

Author’s proceeds are being donated to a branch of Mencap that directly benefits a young Street family descendant with learning disabilities.

See also: The enduring appeal of AG Street