Why discounters could be the best deal yet for farmers

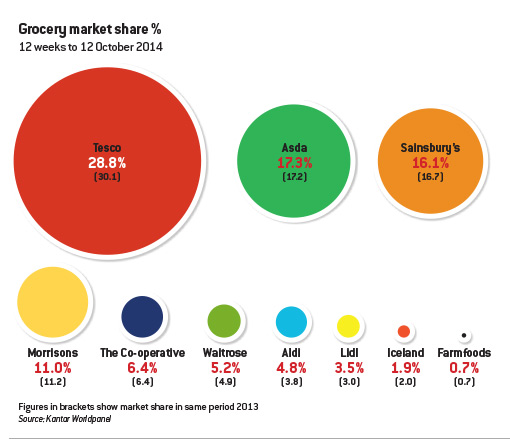

The landscape of the food groceries market is changing dramatically. While the mainstream supermarkets – Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons – remain dominant in terms of market share, their grip on the nation’s shopping baskets is loosening.

Food discounters such as Lidl and Aldi are taking the big boys on and with impressive results.

Fraser McKevitt, head of retail and consumer insight at Kantar Worldpanel, describes the growth of the discounters in recent years as “phenomenal”.

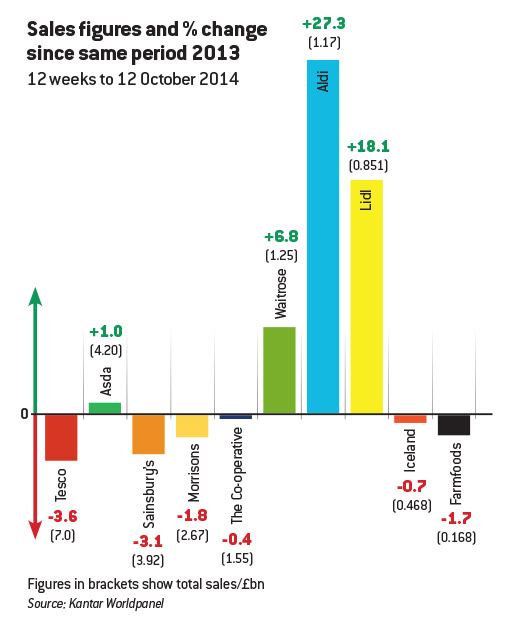

Sales at Aldi – which has recently launched a major new TV advertising campaign – grew 27.3% in the 12 weeks to 12 October compared with the same period last year and the discounter has achieved double-digit growth since the beginning of 2011. Lidl’s performance was also extremely strong, with sales up 18.1% in the same period.

Meanwhile, the combined market share of the Big Four has dropped from a high of 77.7% in January 2012 to 73.2% today, while that of the discounters reached its highest figure so far in July, at 8.5%.

“The groceries market moves relatively slowly, so within that context we are seeing a big shift at the moment,” says Mr McKevitt. “[The discounters] have moved from being niche retailers to mainstream.”

The discounters are not new to the UK, but consumer habits have changed as a result of squeezed incomes and more online shopping. Instead of visiting big out-of-town supermarkets, shoppers are tending to do smaller, more frequent shops in local stores.

“Aldi and Lidl have been in the UK for many years but they seized the opportunity from the financial crisis in 2008 to cut people’s bills sharply,” says Mr McKevitt.

They opened stores quickly and widened their nets through marketing campaigns that won over more well-heeled shoppers concerned with quality and provenance. As a result, the demographics of Aldi’s customers are now similar to those of the bigger retailers, says Mr McKevitt.

Consumer still want choice, but there is “an appetite for simplicity,” and the discounters are masters of this, offering fewer products and focusing on consistently low prices rather than endless promotions. “People know what they stand for,” says Mr McKevitt, whereas the larger retailers have struggled to differentiate themselves.

Straightforward relationships

The good news for farmers, given the rise of such businesses, is that the most common word used by suppliers to describe working with Aldi and Lidl is “straightforward”, says Phil Hudson, NFU head of food and farming. They drive a hard bargain at the start and are intensely focused on price, but “once they arrive at a deal, that’s a deal”.

Most aspects are negotiated from the outset and don’t change. Discounters still ask for supplier contributions and extended payment terms, but the supplier normally knows about it when entering into a contract, rather than in retrospect as is often the case with some of the larger retailers.

The discounters place orders for a smaller variety of products, and don’t tend to change orders at the last minute or switch suppliers so readily. This is less onerous on suppliers’ stocking systems.

Duncan Swift, head of the food advisory group at corporate consultancy Moore Stephens, adds that other buying practices commonly used by retailers to extract money from suppliers, such as seeking contributions towards marketing and shelf positioning, are still “part of [the discounters’] toolkit”. However, they tend to use them less.

They also seem to rely more on suppliers’ quality checks or independent marks such as Red Tractor, rather than conducting checks themselves, says Mr Swift.

Overall, they appear to be less involved with their supply chains, says Mr Hudson. Aldi does not have direct supplier relationships, apart from with producer-packers in the horticulture sector, he adds. This means the discounters do not tend to have producer development groups as Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons do.

Commitment to British produce

Encouragingly, Aldi and Lidl are developing a stronger British produce offering. Lidl stocks 100% fresh British meat and poultry with the Red Tractor logo and about 40% of Aldi’s overall produce range is British and 100% of its “core range” of fresh meat is Red Tractor approved. It also sells 100% British lamb year round.

Aldi in particular is keen to stock British produce, says Mr Hudson, which could open up opportunities for British farmers.

“They want to supply British produce, so [farmers] need to work out how to keep supporting them as they grow,” he says.

The key challenge now, which the NFU is pushing for, is a concrete plan about how they intend to procure the increase in British produce as they grow. Will they also need to develop direct relationships to do so?

Race to the bottom

But while there are many positives for farmers, there are also concerns. In a bid to stave off the discounters the leading retailers have dropped retail prices, which in turn has piled extra pressure on the supply chain. The impact on farmgate prices is not always clear cut – in many instances the major supermarkets have claimed to fund discounts themselves rather than pass them back to farmers.

There is a range of other influencing factors, such as slowed domestic beef and lamb consumption and a large pool of liquid milk which have contributed towards depressing farmgate prices in 2014.

Mr Hudson says there is “no real evidence” that the lower prices discounters pay suppliers are undermining those that others pay. However, with a continued downward trend there is concern about where prices could go.

Discounters can sell at lower prices because they have a simple, cost-efficient model, with fewer product lines, fewer suppliers, and a smaller buying structure.

But when the larger retailers – with their complex supply chains, thousands of products and large team of buyers – cut shelf prices, their margins are more tightly squeezed. Retailers wanting to address margins then often look for a quick win by going to suppliers, warns Mr Swift. This has led to “a serious ratcheting up of pressure” in the past 12 months, across all retailers, he says.

The practice of levying financial contributions from suppliers is widespread, as is the extension of time taken to pay suppliers, says Mr Swift.

Discounters do ask for financial contributions from suppliers, but these tend to be smaller and are usually discussed at the outset, he says.

So while prices agreed between suppliers and discounters are usually lower than with one of the Big Four, once higher contributions are taken into account, the overall amount a supplier is left with is more on a par, says Mr Swift.

Pressure only likely to increase

Grocery market inflation has just seen its thirteenth successive fall (to -0.2%), with a basket of everyday items now costing less than it did at the same time last year, says Kantar Worldpanel.

Consumers are benefiting in the short term, but pressure on the supply chain is likely to increase and move down to farm level. What this does to how food is valued and those who produce it, will become clearer as the market develops.

One thing is certain, how the discounters grow will be key.

Supermarket | Number of stores | Sales | Profit |

|---|---|---|---|

Aldi | 500 in UK, 10,000 across 17 countries | Year to 31 December 2013 – UK sales up 30% to £5.27bn | Year to 31 December 2013 – UK pre-tax profits up 65.2% to £260.9m |

Lidl | 600+ in UK, 10,000 across Europe | 2013-14 – expected to exceed £4bn | 2013-14 – Unavailable |

Morrisons | 605 in the UK | Year to 2 February 2014 – turnover down 2% to £17.7bn | Year to 2 February 2014 – underlying profit before tax down 13% to £785m |

Tesco | 3,378 in UK, 6,784 across 12 countries | Year to 22 February 2014 – UK sales down 0.1% to £48.2bn | Year to 22 February 2014 – UK trading profit down 3.6% to £2.19bn (under investigation) |

Iceland | 833 in UK, 11 in Eastern Europe, also sells products to 30 countries | Year to 28 March 2014 – group sales up 2.7% to £3.71bn | Year to 28 March 2014 – unavailable |

Asda | 547 in the UK | Year to December 2013 – up 2.1% to £23.3bn | Year to December 2013 – operating profit up 18.2% to £993.9m |

Sainsbury’s | 1,203 in the UK | Year to 15 March 2014 – up 2.8% to £26.4bn | Year to 15 March 2014 – underlying profit before tax up 5.3% to £798m (profit before tax up 16.3% to £898m) |

Farmfoods | 300 in the UK | Year to 28 December 2013 – group turnover £689m | Year to 28 December 2013 – group profit before tax £15.8m |

The Co-operative | 2,779 in the UK | Year to 4 January 2014 – down 2.8% to £7.24bn | Year to 4 January 2014 – underlying profit down 8.2% to £247m |

Waitrose | 347 in the UK | Year ending 25 January 2014 – up 6% to £6.1bn | Year ending 25 January 2014 – operating profit before tax up 6.1% to £310m |

Opinion: Too soon to give a ringing endorsement

Jez Fredenburgh, Business reporter

The statistics on the grocery market are pretty clear – we are starting to see a small but significant shift in power away from the Big Four. But the rapid rise of the discounters raises questions.

Many suppliers do seem to find dealing with discounters more straightforward and this can only be a good thing. As Aldi and Lidl grow, will suppliers feel more empowered to choose a retailer that offers less stress?

Other retailers may even be encouraged to exchange their complicated and costly way of dealing with suppliers for something simpler and more up front.

A straightforward approach isn’t everything, though. The discounters typically have a more hands-off approach to their supply chains – which is great if you’re a farmer or processor wanting to get on with your day job, but perhaps not so good for knowing what is going on in the supply chain.

Discounters also tend not to develop their relationships with suppliers beyond that of simply buyer and seller. In contrast, the Big Four have producer groups, on-farm research projects and knowledge exchange initiatives – all of which add value to suppliers.

Aldi and Lidl’s current eagerness to sell British produce is encouraging, but the farming industry has yet to see a concrete plan of action for how this will develop as they grow.

It is yet another reminder of the fact we simply don’t know that much about the discounters. The signs are promising but without greater transparency it is difficult to come to a definitive view.