Towards Net Zero: How to reduce emissions and store carbon

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Farming has been recognised for the key role it can play in helping the UK meet its net zero emissions target by 2050, with individual farmers being encouraged to do their bit.

There’s no magic bullet or one-size-fits-all approach, say experts, who highlight that we will need a multitude of different options to both reduce emissions and capture or store carbon in soils and woodlands.

“Achieving net zero in agriculture is challenging,” says Dave Freeman, business area manager for agriculture with Ricardo Energy & Environment.

See also: Net-zero demo farm’s three-pronged approach to cutting carbon

“There are three main greenhouse gases [GHGs] to deal with from agricultural activities, all of which are produced within a complex biological system.”

The main GHGs in agriculture

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) comprises 12% of total emissions and is created by energy use, specifically combustion

- Methane (CH4) accounts for 56% of farming’s emissions and comes from enteric fermentation in ruminants and manures

- Nitrous oxide (N2O) forms 31% of the industry’s emissions and comes from soil as fertiliser breaks down and nitrification occurs

Source: National Air Emissions Inventory 2012

For net zero to be reached, these GHG emissions need to be reduced, while carbon has to be removed from the atmosphere and sequestered, or stored indefinitely, he explains.

“Farming can’t be decarbonised completely. Emissions are part of the biology of plants and animals growing,” he says. “There will have to be some carbon sequestration to balance or offset the remaining emissions.”

What is net zero?

Net zero is the balance between all GHG emissions and removals in the annual cycle of agricultural production systems.

The emissions, which are losses of GHGs from farming activities, go into the atmosphere and contribute to warming. In farming, these arise from manures, fertiliser use, enteric fermentation and fuel use.

Removal of GHGs from the atmosphere is achieved by growing things. This sequesters carbon dioxide into carbon in biomass, both above and below ground, and accumulates organic matter. On farms, woodland, hedgerows, grassland and soils are involved in this process.

Where to start

In the first instance, targeting waste and inefficiencies can help bring emissions down while land use change can give opportunities for removal – forest and grassland are carbon stores, while cropped arable land emits carbon, for example.

Cattle can be a large emissions source, mainly from the digestive process of enteric fermentation, acknowledges Mr Freeman, who suggests that the first thing to do is to see whether the system is working as efficiently as possible.

“Actions that are taken to improve the carbon balance tend to have benefits for other parts of the business. So it makes sense to target these improvements to get multiple benefits, such as reduced costs and better margins.”

Given the current situation, a focus on fertiliser efficiency and reduced rates, for example, will both drive emissions reductions and manage costs, he notes.

Carbon audit

Start by understanding what the emissions sources on your farm are and where the removal opportunities occur, advises Mr Freeman.

For that, he suggests using a carbon audit tool. While they do require data and effort, they will help to show you where your major emissions sources are as well as how they vary across and within enterprises.

“Once you have a measure of these, you can start to look for opportunities to reduce them. Then you can plan your actions and make changes.”

He warns that none of the carbon footprinting tools are perfect and all have pros and cons, however he sees them as important for helping farmers understand their starting point and are really useful in planning actions and tracking progress over time.

“Currently most of them lack sequestration or carbon removal capability and some don’t include the uncropped areas. Consistency between the tools can be an issue – so select the one best suited to your situation and stick with it.

“Fortunately they are evolving all the time and continually improving in the information and insight they provide.”

See more on carbon tools

Reducing, offsetting or removing?

Once the main sources of GHG emissions on farms have been identified, farmers can look for opportunities to reduce them.

That may be by increasing productivity, making better use of inputs, or changing farm practices.

“Again, as this is not about one type of farming or one system, there will be something for everyone. Individual businesses will be making different decisions,” Mr Freeman says.

The next step is to look for offsetting or removal opportunities. Assessing what assets you have as a land manager allows you to identify areas of land that can be changed.

“Less productive land could go into an agri-environment option, such as wild bird cover or a pollen-rich flower mix, for example.

“Agroforestry or silvopasture may be appropriate for marginal areas, or even woodland. Of course, putting the right trees in the right places is important.”

Storing carbon

Where carbon sequestration is the aim, consider practices that involve the production of both above- and below-ground biomass.

New tree plantings, new pasture and hedgerows all fit the bill, while old historic woodlands, which tend to be in equilibrium, need to be managed and protected.

Moving to permanent pasture or new woodland are the most sure-fire ways of long-term carbon storage in the soil, notes Mr Freeman.

“Soil has huge capacity to store carbon, but farmers need to protect it and build it. This can’t happen unless they do something different with it to get the full benefit.

“That might mean changing the way they use the land rather than the way they interact with it.”

Three pillars

NFU climate change adviser Ceris Jones points out that there will need to be a partnership approach for farming to reach net zero by 2040 – which is the NFU’s ambitious pledge.

“We need to work with others – such as the government and the supply chain – to achieve the balance between emissions and taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.”

She highlights a range of practices for farming businesses intent on making changes, which fit into one of three pillars:

- Reducing emissions by being more efficient This involves managing the things that give rise to GHG emissions, such as livestock feed policy and arable nutrient management, as well as by increasing productivity.

- Storing carbon on farmland From fine-tuning grassland management to introducing cover crops and integrating livestock onto arable farms, there are possibilities for storing carbon in soils and in woody vegetation.

- Boosting renewable energy and building a zero-carbon economy Bio-energy has enormous potential for farms, from the use of anaerobic digestion to produce energy to the planting of perennial energy crops such as miscanthus.

NFU analysis shows that it is possible for the industry to get to net zero, she adds. “A quarter of the challenge will be achieved by increasing productivity, with a further quarter coming from carbon storage.

“The final half will come from bio-energy measures – for which we do need a strong domestic bio-energy chain.”

Actions that can alter the GHG balance

Land use

- Conversion of arable land to grassland

- Agroforestry

- Woodland planting

- Woodland and hedgerow management

- Wetland/peatland restoration

- Preventing removal of farmland trees

Crop production

- Reduced tillage/zero tillage

- Leaving crop residues on soil surface

- Soil amendments

- Using cover/catch crops

- Growing legumes in the rotation

Livestock production

- Disease management

- Using sexed semen

- Feed additives in rumen diets

- Improving herd fertility

- Optimising feed strategies

Nutrient/soil management

- Use of nitrification inhibitors

- Improved nitrogen efficiency

- Biological N fixation in rotations

Other

- Carbon auditing tools

- Nutrient management plans

- Renewables

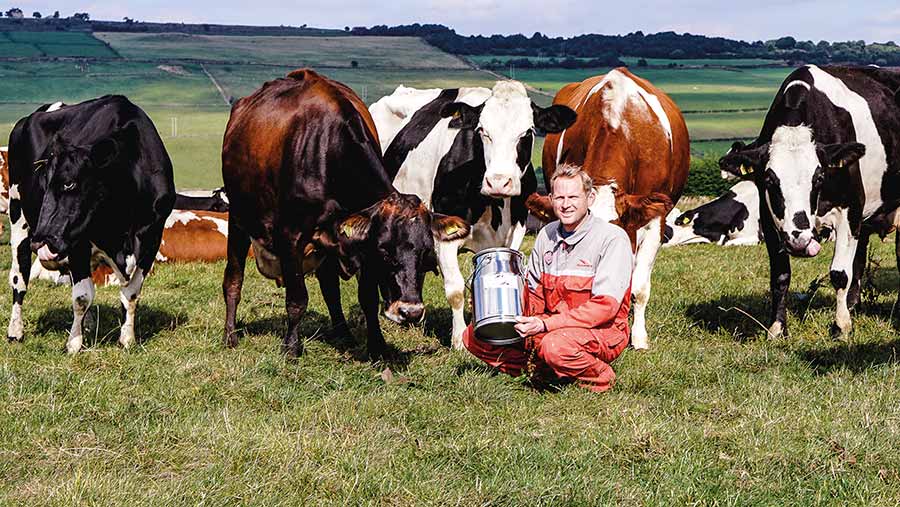

Transition farmer: Eddie Andrew, Dungworth, Sheffield

© Our Cow Molly

Dairy farmer Eddie Andrew is reducing his carbon footprint by supplying milk to a key customer in stainless steel churns instead of plastic bottles.

Mr Andrew milks 90 cows at Cliffe House Farm, Dungworth, on the outskirts of Sheffield.

He supplies about 160,000 litres of milk annually to Sheffield University’s cafés and restaurants under the farm’s Our Cow Molly brand.

Switching to stainless steel churns has reduced plastic waste by 87,000 single-use bottles a year. Each steel churn holds about 10 litres of milk. When empty, they are returned to the farm where they are washed, refilled and reused.

Working with Mr Andrew, the university invested in 70 churns. The decision has reduced the carbon footprint of milk delivery to the university by more than 65% – equivalent to some 6.5t of carbon dioxide every year.

The best way to deliver milk was researched by the university’s Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures. Previous studies considered milk cartons or glass bottles – but these were deemed impractical for a commercial business using large volumes.