Survey shows great potential for on-farm renewables

Some 76% of farmers believe renewable energy generation could play a greater role in the future of their businesses, a Farmers Weekly survey has revealed. The survey gathered opinion on farm-based renewable energy from nearly 700 farmers across the UK.

The research was carried out as part of “Farm as Power Station”, a joint initiative by Farmers Weekly, Nottingham Trent University and Forum for the Future, which aims to bring about a step-change in the uptake of sustainable farm-based energy production across the UK.

The survey revealed that renewable energy has become a significant area of farm diversification and would continue to be so over the next five years. There remains healthy debate about whether energy generation is a distraction from producing food, yet according to this latest research 73% agreed with the idea that on-farm renewable energy should play a major part in meeting future energy needs in the UK.

But can farmers produce food and energy together? We asked what they thought the British countryside should be used for and unsurprisingly producing food was top of the list for 99%. This was followed by education and access to nature (83%) and preserving biodiversity and ecosystem services (79%). However, 77% felt the countryside should be used for generating energy, and 74% agreed that land should be used for producing fuel and fibre as well as food.

The generators

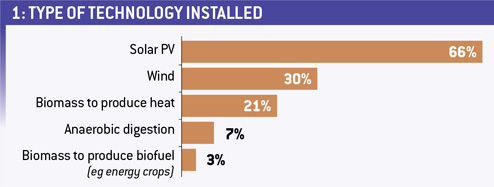

Thirty-eight percent of respondents said they currently generated renewable energy, with the most popular technology types being solar PV (66%), wind (30%) and biomass for heat (21%) – see table 1.

For 36% of generators, the energy was used solely on-farm but for the majority (53%), the hope was to use a proportion on the farm and export the rest into the grid. Only 10% was generated solely to sell on the open market.

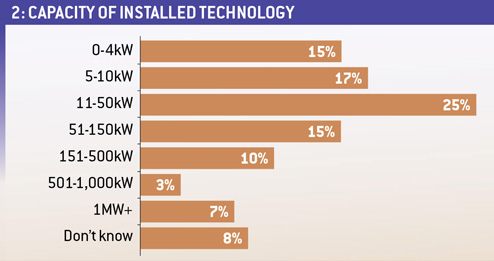

The average installed capacity on-farm was 176kW, but the majority of schemes fall within the 11-50kW band (see table 2). However, only 7% had an installed capacity of more than 1MW, indicating that if on-farm energy generation is to be a serious player in the national energy mix, scale remains a challenge.

But that’s only part of the picture. For many farmers, renewable energy is about cutting their own energy use rather than exporting to the grid. Fifty-seven percent believed that renewable energy had saved them money in the past year, while 37% expected it to do so in the future. The average energy cost saving per farm in the last year was £2,700, according to the respondents.

As a result, 75% of those who were already generating renewable energy were likely to invest again in the future. Wind was the most popular next step (37%), closely followed by biomass to produce heat (31%) and solar PV (27%). It would seem that despite a lack of confidence in the government’s support for renewables technology, there is a willingness by farmers to look at further investment.

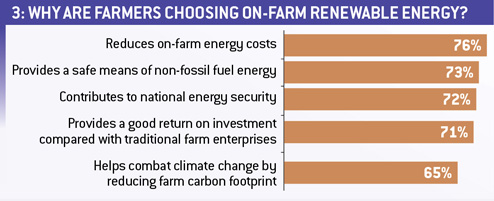

Some 76% of farmers (see table 3) felt that the main benefit of on-farm renewable energy generation was that it reduced energy costs in the business. However, this was closely followed by a sense of contribution towards a national agenda; 73% felt it provided a safe means of non-fossil fuel energy and 72% felt it contributed to national energy security. But perhaps most telling was the fact that 71% felt renewable energy provided a good return on investment compared to more traditional farming activities.

The prospectors

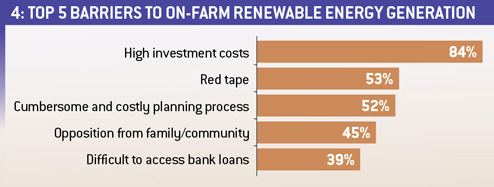

Of those not currently generating renewable energy, 61% said they were likely to invest in some form of the technology in the next five years. Solar PV (79%), wind (61%) and biomass for heat (27%) were deemed to be preferred technologies to invest in. This huge interest in the potential of the technology suggests a conflict between what farmers are willing to do and what they are able to do. On one hand, farmers feel comfortable that this is something they should be doing, with 81% believing their family, neighbours and fellow farmers would approve of their decision to invest in the technology. However if this is so, why are there so many prospectors and not more generators? The answer to that perhaps lies in the long list of barriers (see table 4) that have impinged on farmers’ ability to invest in renewables.

Barriers to uptake

Any technology will be faced with challenges when it first arrives in the marketplace, but the barriers preventing renewables uptake to date have proved insurmountable for many farmers. Challenges range from the size of capital investment required and a cumbersome planning process through to a lack of credible information and local opposition.

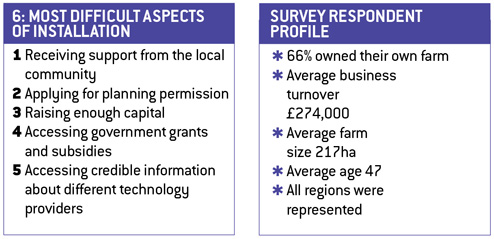

Receiving support from the local community has proved the most challenging aspect of on-farm renewable energy generation for respondents to the survey (see table 6). Despite positive views from farmers about the balance that can be struck between producing food alongside energy in the countryside, it’s clear more work could be done in educating the wider public about that potential.

Other difficulties included the well-documented struggle to get through planning permission and the ability to raise enough capital to get started.

How can more farms generate renewable energy?

The survey revealed that barriers remain a source of frustration, but it also made clear that there are opportunities to improve the situation.

Communication

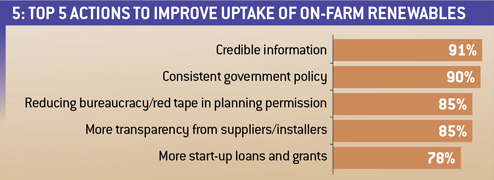

One of the easier problems to address is the need for more credible information around the social, economic and environmental impacts of renewable energy, with 91% saying this was important (see table 5).

For Lucy Hopwood, head of biomass and biogas at the National Non-Food Crops Centre, it is about getting the simple things right.

“The easy win is around communication. The right communications, from ministerial level down, would make a huge difference in supporting farm-scale renewable energy generation. It’s a relatively quick and easy win that would bring about confidence and certainty and result in more collective effort across the board,” she says.

Consistent government policy

Better communication is needed but consistent government policy was also deemed important.

Dr Jonathan Scurlock, chief renewables advisor at the NFU says: “Greater consistency in high-level renewable energy policy across DECC and DEFRA (as well as DfT) would help – there have been too many conflicting messages, and not enough emphasis on long-term goals to reassure investors – such as decarbonising electricity production by 2030, or supporting a specific EU-wide renewables target for 2030.”

Grid connection

For Steve Edmunds, Farmers Weekly‘s 2012 Green Energy Farmer of the Year, a more strategic approach is needed to make grid connection easier and more accessible for generators.

“The quality of the grid is poor for devolved generation and we need the government and district network operators to take a more strategic view on where they would like additional generation on the grid. The current ad-hoc approach to grid connection isn’t good enough and leaves farmers footing the bill,” says Mr Edmunds.

Community engagement

Dr Nick Cheffins of sustainability consultancy Peakhill Associates says the focus must be on driving greater community involvement.

“I’d want to see policy that makes it a lot easier for communities to get involved,” he says. “The default position should be a co-operative aspect in energy developments. If we got that, then we’d tackle a number of the other barriers at the same time. Communities, making decisions for themselves, are always going to work better than a third party coming in asking for permission.”

New Feed-in Tariffs

Green energy supply company Good Energy says the focus should be on encouraging the government to play a more active role in supporting decentralised electricity generation, particularly on farms.

Ed Gill, head of external affairs at Good Energy, says: “We believe the electricity market reform process should introduce a new Feed-in Tariffs scheme for 5-50MW sites, to encourage investment in medium-scale renewable developments. This would create new opportunities for the on-farm generation at this scale, particularly since larger-scale developments are more likely to rely on leveraged borrowings (rather than existing cash reserves) which farm-based projects are well positioned to access.”

Summary

On-farm renewable energy has gained ground since 2010, when DEFRA reported that only 5% of farmers were producing energy. It seems that the belief from farmers is that they can produce food and energy together.

Iain Watt of Forum for the Future is also heading up the Farm as Power Station project. He says: “Despite the impressive efforts of many individuals and organisations, the potential of farm-based renewable energy is not yet being fully realised.

“We’d like to see a planning and policy regime that does more to support farm-scale renewables, better financing arrangements, a revamped grid and an established market for farm-grown green power. We think we can achieve all that and more through co-ordinated action.”

Professor Eunice Simmons of Nottingham Trent University also believes more could be done to realise the potential of renewables technology. “Innovation is needed within the energy system in order to utilise home-sourced, sustainable energy that we know is there. We believe farms have a significant role to play in achieving this,” she says.

For more on this topic

Find out more about our farm renewables project