How agriculture policies affect our Arable Insights farmers

Flexibility is needed with overwinter stubble options, as spraying volunteer potatoes is part of an integrated approach to blight and potato cyst nematode © Tim Scrivener

Flexibility is needed with overwinter stubble options, as spraying volunteer potatoes is part of an integrated approach to blight and potato cyst nematode © Tim Scrivener Uncertainty still reigns over Scotland and Northern Ireland’s future agricultural policy, while English farmers are now able to apply for Sustainable Farming Incentive (SFI) income, albeit having had their Basic Payment Scheme funding cut by 50%.

Farmers Weekly spoke to three of its Arable Insights farmers to understand what this means for their businesses.

Scotland: Amy Geddes

The Scottish government’s Agriculture and Rural Communities Bill was finally published in late September, setting out a new framework to replace the Common Agricultural Policy.

The bill aims to deliver the government’s vision to become a global leader in sustainable and regenerative agriculture, by incentivising the country’s farmers to produce more food sustainably, support biodiversity restoration and drive low-carbon approaches to improve resilience, efficiency and profitability.

See also: Scotland trip inspires Canadian grower’s distillery

But just as English farmers complained for a long time about the lack of detail, Amy Geddes says Scottish farmers haven’t exactly been flooded with information.

“I’ve an understanding of the general direction and it is good to have the certainty that we’re fully supported [in terms of previous levels of funding] until 2025.

“But beyond that it’s important to have information that will affect you five or 10 years down the line for rotation and business planning.

“We don’t have that detail, and there must also be at least a question mark over whether the Scottish government can secure the funding required from Westminster.”

Amy has volunteered previously for the arable farmer-led group that fed into the Agricultural Reform Implementation and Oversight Board, and will look to continue that following a call for volunteers to “shape the future”.

It’s important to be part of these discussions to make sure the policy is fit for purpose and practical for both farming and nature, she says.

“There’ll be some financial return for this, which will maybe help to get more people involved or to give up their time.”

Sustainable farming

Amy says her farm is only at the beginning of its sustainable farming journey.

“I don’t think we’re regenerative in any shape or form, but we are at the beginning of understanding how we can farm by moving less soil with hopefully lower inputs, while maintaining a sound marketable yield.

“I’m personally interested in building up the nature network on the farm.

“We’ve done a lot of hedging in the past 10 years through the Scottish Rural Development Programme, we have small on-farm woodlands and some ponds that we need to regenerate.

“I would like to combine that with thinking about the water supply on the farm in terms of crops we might grow in future that require irrigation, so there are lots of positive things we can think about to build resilience into our farming system.”

The understanding of how farmers are expected to reach the desired end goals is currently missing, although a list of potential agricultural reform measures has been published, she notes.

The list includes practices such as retaining overwintered stubbles, using minimum or no tillage, reducing inputs, growing legume crops, diversifying rotations, intercropping and adding herbal leys, plus other options familiar in previous environmental schemes.

“The list is useful, but it would be more useful to know what we might expect to return from that.

“We’re running a business at the end of the day, so what is the payback? There is no mention of figures yet.”

Flexibility will also be crucial, she stresses. “For example, in the winter cover option it suggests leaving stubbles unsprayed and undisturbed until 1 March.

“That’s difficult to achieve with potatoes in the rotation. We try to avoid ploughing over winter, but there’s only so much work you can do in the spring window.”

And she sprays for volunteer potatoes because that’s part of her integrated pest management approach for reducing blight and potato cyst nematodes.

“So, little things like that, without flexibility, can make it really challenging and are an immediate barrier to adopting a measure.”

She also hopes there might be some capital investment to help with new practices.

One example is intercropping, she says, which the farm has tried, but they found separating overly complex using extra screens over potato boxes and their own dresser.

“It would be good to have some capital investment for separation.”

Northern Ireland: Simon Best

A lack of a sitting government is adding an extra level of complexity to implementing a new agricultural policy in Northern Ireland, explains Simon Best.

“There’s still significant work going on in the background. Basic payments are still in place for this year and next.

“It’s then planned to move to what is called transitional farm sustainability payments, which I understand will introduce new conditions to the current situation.

“And then, in 2026, further conditions will be added, probably around environment and carbon. So there is a journey in place, but it’s slower than the rest of the UK.”

A major frustration is that Simon’s Environmental Farming Scheme wider agreement ends this year without its replacement, Farming with Nature, available yet.

“It means for the first time in 20 years, we won’t be in a scheme next year.

“We’re hopeful the new Farming with Nature scheme will start to be rolled out with some innovation trial pilots first.

“It’s slower progress than hoped, although it is better to have a scheme that is fit for purpose.”

With the vision for Acton House Farm to be at the forefront of farming sensitively with the environment, he hopes he’s well positioned to be chosen for a pilot, as he was for a two-year pilot scheme offering £330/ha additional support for growing protein crops.

“That’s been a huge success in increasing the amount of home-grown protein in Northern Ireland, which we hope will continue.”

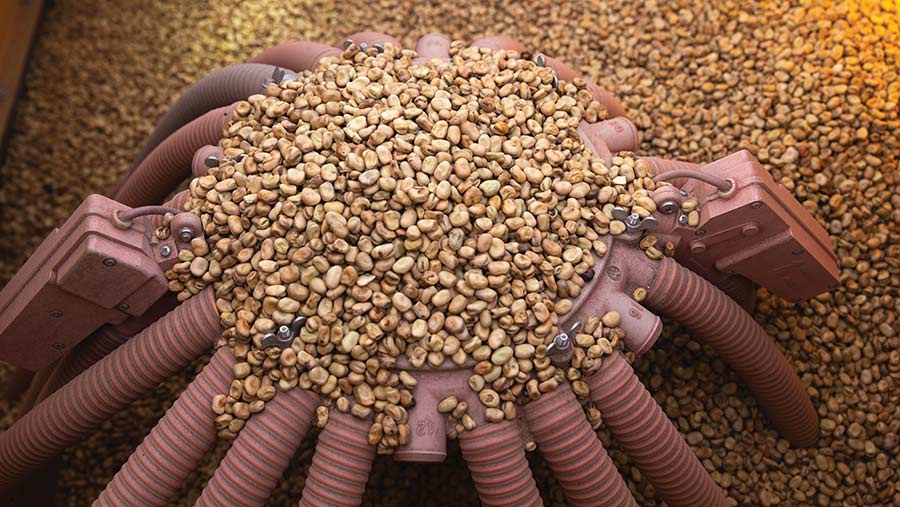

Simon Best says more needs to be done to develop protein crop markets in Northern Ireland © Tim Scrivener

Bean trials

Trials feeding home-grown protein to dairy have proved successful to help develop markets, he adds, but more needs to be done – for example, rolling it out to the pig sector.

Another initiative that should help arable farmers progress in the direction required is the Soil Nutrient Health Scheme.

The scheme, which provides standard soil phosphorus, potassium, sulphur, magnesium, calcium and organic matter analysis from every farm, is being rolled out over four years across four zones, with Simon’s farm in the initial phase.

“It’s voluntary, but there is a possible effect on future payments for anybody not in the scheme, so it has had a significant 91% uptake in my region.

“It’s a brilliant initiative from a management perspective – we’ve got the entire farm now analysed with GPS points, so we can repeat it in the future.”

Nutrient run-off maps are being created from the analysis, which will help the farm avoid overapplication in phosphate-sensitive areas.

With future payments almost certain to reduce, taking advantage of incoming schemes will be important, which is why the current void is frustrating.

“We’re certainly not in a place to survive without support,” Simon says.

“We don’t have premium markets on tap to replace support, so we are dependent on some form of replacement scheme and I’d also see environmental and carbon schemes as opportunities for the farm to bridge the gaps and remain viable.”

England: James Sills

East Anglian grower James Sills is finding applying for the SFI not dissimilar in process to an online full Mid-Tier Countryside Stewardship application.

“It’s a bit different to the simplified arable offer, but not radically different to the full-fat version. There are a few ways of viewing information that are slightly easier and, in general, application looks fine.”

But he has hit a significant hurdle, albeit potentially specific to his circumstances, that has prevented him applying.

About half of the farm is currently in a Mid-Tier scheme, mostly overwintered stubbles (AB6) and flower-rich margins and plots (AB8), with a new one due to start 1 January, if approved.

He wants to supplement this with a small number of SFI options, including the no-insecticide offer on part of his cropped area, despite some issues with barley yellow dwarf virus last season.

“But we’ve hit a brick wall as SFI and Mid-Tier don’t seem to be talking to each other terribly well.”

James Sill’s AB8 flower-rich margin © James Sills

His problem is that he is unable to select the no-insecticide offer on fields that have been included for AB6 in the new Mid-Tier scheme.

“AB6 won’t come into effect after the next harvest, but it won’t let us apply for no insecticides on those parcels even though we’ll have a spring crop going in first.

“It feels as if there’s an interface issue between SFI, which can run off sync with calendar years; Mid Tier, which runs in calendar years; and cropping, which doesn’t.”

That means growers will need to think carefully about when to apply for SFI.

For example, applying in October could incentivise changes in behaviour to delay drilling to claim no-insecticide payments, whereas registering a field in January could leave growers feeling trapped if the weather is warm and there is a barley yellow dwarf virus risk when drilling.

“In theory, you can apply in any month, but if you’re largely an autumn cereal grower it could make sense to apply in September or October to make those situations easier, so your three-year period ends in time for the next cropping cycle.”

James Sills may consider the SFI no-insecticide offer despite seeing barley yellow dwarf virus last season © Blackthorn Arable

Tussocky grass option

Except for the insecticide-free offer and a couple of tussocky grass options that he thinks will work better on a few small corners, he sees little reason to switch more wholesale into SFI, having had the fortune to still be able to apply for Mid Tier.

“Other than the insecticide-free options and if a direct-drilling payment is introduced, there isn’t much we haven’t seen before in Mid-Tier, at least for an arable farm.

“Don’t expect it to revolutionise your farm, but it might provide a useful top-up is the way to think about it from an arable farming perspective.”

One concern he has is that some of the offers which now appear to be rotational might not deliver on their aims.

“For example, the old AB8 in Mid-Tier – flower-rich grass margins – which has been suggested could be a one-year rotational option.

“I think that is massively contorting what the option was designed for, as our experience is that it only really delivers the benefits 18 months into the agreement.

“Instead of trying to make old options fit, they should be designing new ones that are specifically designed to fit into rotational slots.”

Overall, he thinks the landscape is much less friendly for farming than before Brexit.

“While the budget has been protected, the number of actual pounds delivered to farm’s bottom line is far from the original promise that support wouldn’t be reduced.

“We’re facing a much tougher world and obviously our competitors across the channel are getting both agri-environment schemes and the equivalent to direct payments, with roughly the same market prices and more favourable trade deals.”

James also questions whether food production is being valued. “It’s causing an identity crisis for some farms, including us, on whether our role is primarily as a food producer.

“Personally, I don’t think of ourselves as food producers – we are more land managers.

“We may even rent out quite a bit of land for anaerobic digestion crops, and will be prepared to do things differently to safeguard our ability to turn a profit somewhat consistently.”