What do fair dealing regulations require of milk contracts?

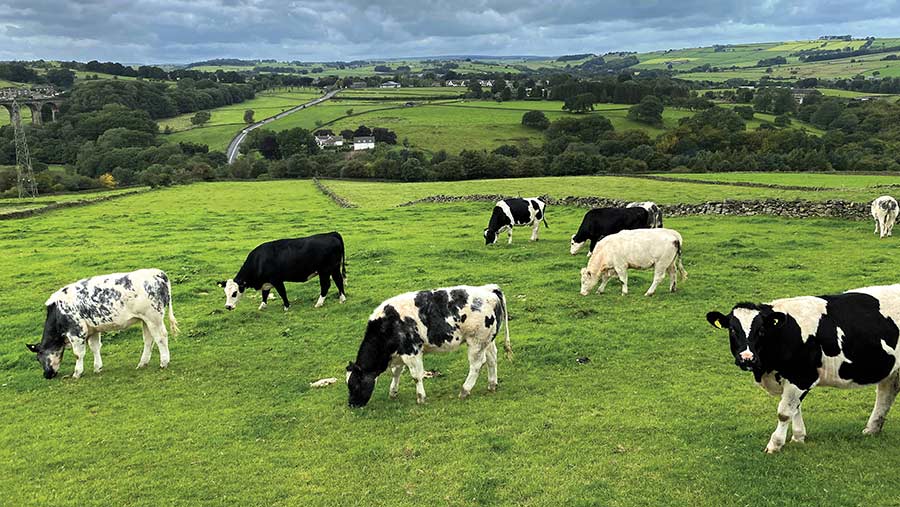

© derek oldfield/Adobe Stock

© derek oldfield/Adobe Stock Milk processors will have to issue new farmgate contracts which comply with the Fair Dealing Obligations (Milk) Regulations 2024. These are currently in draft form and were published on 21 February.

The regulations are designed to tackle dairy supply chain unfairness, following a review by the Groceries Code Adjudicator in 2018, which found imbalances of power in that chain.

This led to a Defra consultation on issues including pricing, volume and timescales, termination and notice periods, flexibility in contracts, bonuses and deductions, exclusivity clauses and dispute resolution.

See also: Defra recruits fair milk contracts adjudicator

Buyers’ ability to change prices and terms without notice or negotiation and even retrospectively were key concerns.

The market ructions during the height of Covid-19 further exposed weaknesses in current arrangements.

The regulations will apply to all farmgate milk contracts apart from those coming into effect within 12 weeks of the regulations coming into force and where all of the milk to be purchased under the contract is acquired within 12 months and 12 weeks of the regulations taking effect.

The draft regulations say written dairy processor contracts must be used between processors and farmer suppliers.

These must be signed by both parties and include a term requiring the processor to act in good faith.

Contracts can be for a fixed period or may be “evergreen” agreements, which simply run until they are terminated.

Contracts must state which of the two types they are, also the date at which the obligation to supply milk starts.

Pricing

The draft sets out that that prices in milk purchase contracts can be fixed, variable or a combination of the two.

Fixed-price contracts

Multiple fixed prices can be set for different periods, but where this is the case, it must be clear which price applies to which period and about start and end dates of each period.

Check contracts carefully

Law firm Napthens welcomes the draft regulations, but says that it could take 18-24 months for processors to get all the new contracts out.

Andrew Holden, head of the firm’s rural team, says: “The key thing is that there will be a lot more certainty and the termination provisions will be limited in a way they were not before.”

Most producers won’t have any issues with the contracts they are offered but they should not assume all is in order, he says, adding that the documents should be checked carefully before signing.

NFU members can use the firm’s contract checker service at a subsidised rate.

They must also set out how prices are to be reviewed in exceptional market conditions.

This could be in force-majeure circumstances, for example, but contracts must be clear about what constitutes exceptional market conditions.

In such circumstances, milk producers must be able to ask for a discussion in the price review and the processor must engage in this within 30 days of the request being made.

Variable-price contracts

Prices cannot be changed more often than once a month or less frequently than three months under variable-price contracts.

When varying the price, only factors set out in the contract can be taken into account.

Producers can ask for an explanation of how a variable price was reached and what factors were taken into account.

The processor must respond to this within seven days and allow an independent third party to examine how a variable price was arrived at.

Exclusive supply

Most current contracts include an exclusive supply clause.

The draft regulations say that exclusive contracts cannot fix the volume to be supplied or penalise a supplier delivering more than a certain amount of milk.

Fixed-volume contracts

Under the draft regulations, these contracts must be for a volume to be supplied over a period of no longer than 12 months, must state the fixed volume and acceptable supply limits above and below that which will be paid for at the fixed-volume price.

They must also give detail on how milk will be priced for any volume below the acceptable supply level.

However, the draft is silent on how to deal with any volume above the upper acceptable supply limit.

Notice periods

Where a milk supply contract is being terminated, producers must be given at least 12 months’ notice unless they are in breach of the contract or they agree to an alternative period.

Producers must give a maximum 12 months’ notice to the processor.

Variations

Processors must consult with producers on any contract changes, these must be agreed in writing and cannot be enforced without the farmer’s agreement, or that of their producer representative.

Cooling off

Producers who take up a new contract will have a 21-day cooling-off period, with no penalty if they decide during the 21 days not to continue with it.

Dispute resolution

Contracts must contain a dispute resolution process so that producers can complain to the processor, who must investigate and resolve the issue.

Enforcement

Defra is recruiting an adjudicator to check that processors are complying with the regulations.

The adjudicator will be able to fine processors up to 1% of their turnover and/or order compensation to be paid to a milk producer when a processor breach has been found.

What happens next?

The draft regulations must pass through both Houses of Parliament.

The timescales estimated by different parties as to when the regulations will become law range from four weeks to a year.

Once the regulations are passed, detailed guidance will be issued by Defra for processors and producers.

Challenges and questions

Under the draft regulations, exclusive contracts cannot fix a volume or penalise a producer through tiered pricing.

Several observers question how this can work with the seasonality required by processors.

Ian Powell, managing director of consultancy The Dairy Group, says: “There could be an issue with tiered pricing in the statutory instrument, relating to varying the price if the producer exceeds a certain volume.

“Almost all contracts have a mechanism for varying the price based on volume and these are needed to recognise the value of milk at different times of the year.

“There are also retail aligned contracts which have a certain volume paid at the aligned price and a lower price above this volume.”

He also points out that the dairy voluntary code provided for no downward variation to the milk price with less than 30 days’ notice and allowed producers to terminate without penalty on a maximum of three months’ written notice following any change made by the purchaser – but there appears to be nothing similar in the draft regulation.

The regulation also does not appear to cater for milk pricing above the upper tolerance in a fixed-volume contract.

John Allen, managing partner of Kite Consulting, says that the regulations will take out some of the anomalies in processor behaviour.

“The key thing is that all processors will have to engage with producers. It’s not about increasing the milk price, it’s about increasing producer representation and equity in the relationship between the parties.

“Some questions such as how the regulation will affect A and B contracts will be addressed by the guidance, which will be issued once the regulations become law.”

“Dairy farmers will get new contracts, but they also need to be aware that this process will give processors a chance to review their milk fields. There’s no guarantee they will continue with all their existing contracted milk suppliers.”

On exclusivity, Adrian Bennett, a solicitor with law firm Michelmores, says: “The current contract model is not compatible with non-exclusivity and processors will need to consider how they reflect these changes in the contracts if they wish to fix volume.”

Even with the changes brought about by the draft regulation, processors will still have the power to determine and vary the price, but they must be able to provide the reasoning for it based on the criteria anticipated in the contract, which the producer will have agreed to.

“Processors will need to think very carefully about the price they are setting and must be able to justify price changes based upon the factors in the contract.”

He cautions that processors will need to guard against a situation where a variable price that runs on for many months at the same level is not then seen by default to be a fixed-price contract.

On the penalties, he says that placing such a stark enforcement mechanism on previously freely negotiated contracts is rather unexpected.

Key points of draft regulations

- Exclusive contracts cannot fix volume

- Price changes to variable-price contracts can only be made having regard to factors set out in the contract, some of which are business-sensitive so producers can ask for changes to be verified independently

- Fixed-volume contracts must set out upper and lower acceptable supply limits – i.e. the base volume plus a tolerance, which will still be paid for at the fixed-volume price

- Contracts must provide a dispute resolution procedure

- 21-day cooling-off period for producers entering contracts

- Penalty of up to 1% of a processor’s turnover can be levied by the adjudicator if a breach is found

- Producers may also be awarded compensation to be paid by the processor