How can dairy exports benefit UK producers?

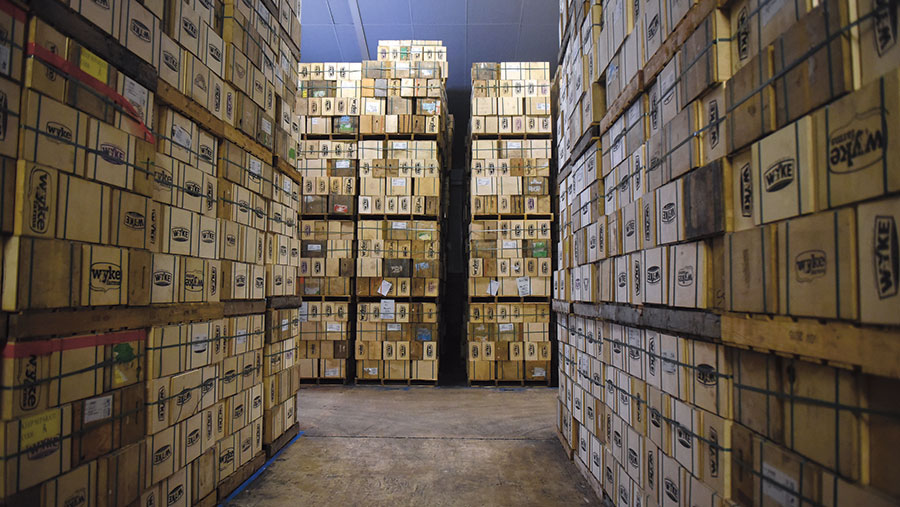

Maturing store © Mary Turner/Bloomberg

Maturing store © Mary Turner/Bloomberg Brexit uncertainty and a hyper-competitive retail environment mean many businesses are gearing up to export the best UK dairy has to offer.

The prospects for this trade are encouraging, with both export volumes and values for all UK dairy products enjoying sustained growth over the past two decades (see “Key figures”, below).

The opportunities

The trend comes on the back of many consumers in other countries prioritising quality over cost, as highlighted by the AHDB Horizon report, International Consumer Buying Behaviour.

See also: Dairy farming climbs to most profitable sector in England

It examined the buying habits of nine of the UK’s prime export targets, including the US, China, India, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Seven of the countries rated quality as the most important factor when choosing food.

The research also highlighted the complexities of exporting dairy products to multiple geographical markets where there is wide variation in what consumers want.

For instance, in Saudi Arabia, the UAE and US, longevity is the primary factor for buying dairy goods, while in Japan and Canada, consumers are more concerned with price.

Key figures

- Between 1998 and 2017 the annual sales value of UK dairy exports increased by 134% to £1.67bn, while export volumes doubled to 1.36m tonnes.

- The EU remains by far the largest market for UK dairy, accounting for 92.7% of UK exports in 2017.

- Shipments to the EU over the same 19-year period grew by 153% in value to £1.26bn, as volumes also shot up 138.7% to 1.3m tonnes.

- Dairy shipments to non-EU countries, which dropped 30% between 1998 and 2017, have picked up by 46% to 106,208t since 2012, with export values burgeoning by 90% to £404.7m.

- While in 2017 the average price for 1kg of UK cheese at export was £3.34 on the EU market, the same volume was worth £4.02/kg to China, £4.47/kg to India, £5.67/kg to the UAE and 102% more to the US than the EU at £6.74/kg, according to HMRC.

After the 2008 melamine scandal caused the deaths of six babies and 300,000 more fell ill due to contaminated infant formula, the average Chinese consumer’s top priority became food safety – a quality that consumers see as synonymous with products carrying the Union flag.

However, diverging consumer demands means understanding the global export market is complex, and comes with significant costs.

UK dairy products therefore remain niche around the world, with the highest proportion of respondents (43%) stating they simply didn’t know how they felt about UK produce as they had had no exposure to it.

The report stressed dairy farmers were the integral link in the supply chain for selling the “farm-to-fork” story of how the food is produced.

Wyke farms exporting strategy

Few people know the difficulty of penetrating individual markets better than Wyke Farms chief executive, Rich Clothier.

Wyke currently lists 167 regions on its exports roster, with 30% of the company’s total production currently being sent overseas.

But Mr Clothier wants to increase this to 50%, while focusing more resources on fewer markets – and it’s all linked to wine.

The “Chablis Index” is part of the Wyke lexicon and is one of the processor’s methods of establishing which new markets to enter. The rationale is if the target society enjoys a glass of French or Australian wine, chances are they will buy some premium cheddar too.

Each new market brings unique challenges to the business (see “Wyke Farms key considerations for businesses considering exporting”), but the benefits far outweigh the costs, says Mr Clothier, who estimates that Wyke’s presence in overseas markets is worth 2p/litre to the firm’s dairy farmers.

Exports have also insulated the processor’s 130 milk producers against exposure to the worst troughs of domestic milk market volatility.

Mr Clothier believes the UK has a long way to go to catch up with the likes of Ireland, whose dairy exports were worth more than double the UK’s at €4.05bn (£3.52bn) in 2017.

“Ireland do very well already,” he says, “Kerrygold butter is in virtually every US supermarket.”

Mr Clothier says it is essential for Defra to do more to help companies export and open up new markets, but also for the government to be less hawkish in world diplomacy.

“I would like to see the UK take a backseat in world affairs. We should be inviting people like [Donald] Trump to the UK with open arms.”

Mr Clothier adds: “He is the leader of the richest country in the world and we are risking trade deals with the states with negative rhetoric. We should be getting on with everyone.”

Wyke Farms key considerations for businesses considering exporting

- Not all milk buyers are active in export markets – are you missing out on farmgate premiums of about 2p/litre?

- Protecting your brand is costly. Depending on the region, it can cost between £10,000 and £20,000 to register a brand and this can take years. It took Wyke a decade to get into Russia.

- Wyke had to go to court in Australia as someone tried to copy their brand. The cheese company won, but at great legal expense.

- Certain products need to be blessed. Rabbis and imams must be flown in to assure religious certification.

- Labelling must be customised for each market. Different countries demand different elements. All of this adds to costs.

- Many countries want 12 months on cheese sell-by dates, whereas the UK requires only eight months.

- It takes nine months for Wyke cheese to reach the Falkland Islands and the taste can change while in transit.

What does it take to export?

Organic dairy co-op OMSCo exports dairy products worth 20% of its annual turnover, but the processor has ambitions to increase this to 50% in the coming years.

Of the exports sent outside of the EU, 60% heads to the US under a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA)-accredited contract.

Milk suppliers must receive individual farm accreditation from the USDA.

OMSCo chairman Lyndon Edwards is one of 40 of the processor’s 250 dairy farmers with that accreditation.

Lyndon Edwards, Omsco deputy chairman

The accreditation is notoriously difficult to achieve, and Mr Edwards says it has assured that he is always pushing himself towards the highest standards.

“We make around a 2p/litre premium from the [USDA] contract, but the costs of adhering to it are higher, so it probably levels out about even,” says Mr Edwards.

“But we enjoy the challenge of always being at the top of our game – as a farm we’ve had to evolve, grow and be really open-minded with what the contract is asking you to do.”

Mr Edwards says the key for his farm business is faultless animal health to guarantee the highest-quality milk – one slip-up and you will lose a market forever, he says.

“We take health so seriously we’ve brought silaging in house to guarantee we get the highest quality. You cannot skip on attention to detail with exports.”

The accreditation also requires the farm to change bedding twice a day and add extra feed enriched with selenium to help increase immunity.

“The quality of the product is as important as the story behind it,” says Mr Edwards.

OMSCo’s number one export brand, Kingdom Cheddar, focuses strongly on branding, with a union flag and images of sweeping green British pastures, which global customers respond positively to, says Mr Edwards.

“Finally, the pricing has to be right – we can’t be more expensive than our nearest rivals or the customer won’t try our cheese in the first place.

“Consumers buy Kingdom on price first and return a second time because of the flavour.”

Kingdom organic cheddar

Mr Edwards admits that belonging to a processor that has the ability to balance its milk supply and sell any surplus abroad may just have kept him in the milk game.

“If we didn’t join OMSCo when we did, we would have experienced the full volatility of the milk market – we would have thought about getting out of milk altogether.”