Exmoor farm harnesses wind resources

West Ilkerton Farm is a 97ha (240 acre) hill livestock farm four miles from the north Devon coast in the Exmoor National Park.

Sitting on a south-west facing hill about 1,000ft above sea level, the strong winds can be a real nuisance, chilling animals, giving silage wrap a life of its own and damaging buildings.

For a long time we suspected it could also be a valuable resource, but weren’t sure what to do about it. Information about wind energy was difficult to obtain and, until recently, it seemed the costs of installing a wind turbine would outweigh the benefits.

Even when the benefits began to outweigh the costs, three main things limited our options: location, connection to the National Grid and, of course, money.

Planning

West Ilkerton is situated within Exmoor National Park, with rights of way running through the farm and a popular area of common nearby. We knew planning permission for a turbine would not be easy to obtain, and that the site we chose would have to be a compromise between exposure to winds from all directions, proximity to the farmhouse and visibility.

Also, permission was more likely to be granted if the output of the turbine matched our electricity consumption. Understandably, large turbines producing lots of excess electricity for export are not encouraged on Exmoor.

Another restriction is that we have a single phase electricity supply, with a transformer which limits the maximum amount of electricity we can export to nine units, or kilowatt hours (kWh). Upgrading our grid connection is out of the question because of the cost and, in any case, purchasing a turbine which can produce more than 9kWh would have involved a substantial bank loan, which we wanted to avoid.

We had one false start about two years ago, when we obtained planning permission for a wind turbine which sounded too good to be true (and was) from a local company which has now ceased trading. Like many others we were taken in by a clever salesman and a flashy website. We got our deposit back, but some other people were less fortunate.

It is now much more difficult for false claims to be made about small-scale wind turbines, thanks to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme (MCS) which independently assesses and certifies microgeneration technologies and installers.

Turbine choice

As it happens, our initial mistake bought us valuable time while we belatedly taught ourselves about wind power, researched other turbines carefully and visited working turbines. We eventually chose an Evance R9000 and submitted another planning application.

Meanwhile, Feed-in Tariffs (FiTs) were introduced for MCS-certified products. FiTs are paid for 20 years for wind power production, whether the electricity is used or exported, and they are guaranteed and index-linked.

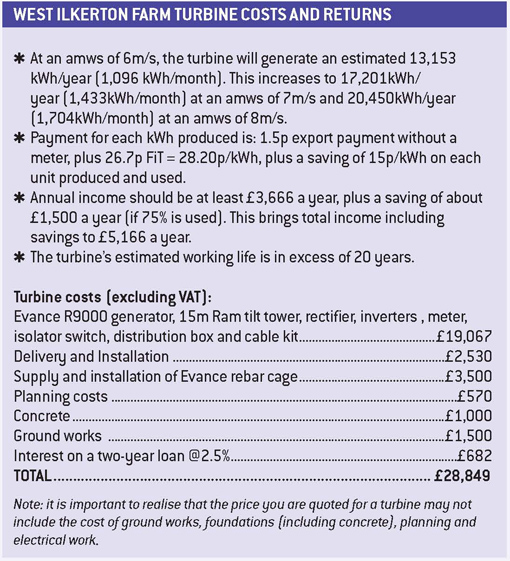

FiTs have improved the profitability of all microgeneration schemes immensely. For example, we estimate the turbine we have just installed will take about five-and-a-half years to pay for itself, but without a FiT payment of 26.7p/kWh it would take about 17 years.

It seems unlikely FiTs will remain at their present levels, so if you’re thinking about a microgeneration scheme it may be a good idea to start the process soon. Planning permission and installation works often take far longer than expected.

Wind power technology has been advancing so fast that it was very difficult to choose a turbine, knowing that whatever we chose would be superseded sooner or later. Eventually we chose the Evance R9000 because it was one of the first to be MCS-accredited, it had a good track record and its estimated output matched our predicted electricity consumption. Another important factor was that we liked the look of it.

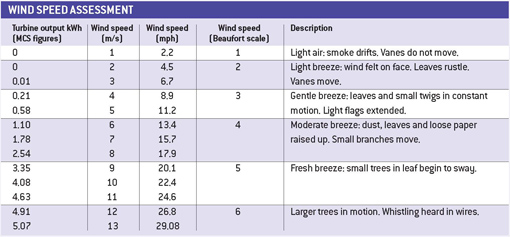

One thing we did not do was measure the wind speed at various sites. Chris is out on the farm so much he knows the parts of the farm which catch the most wind. The prevailing wind is from the south-west, but we also get a lot of north-easterly winds, so we wanted to make use of them, too. He estimated wind speeds on the Beaufort scale (see table above), translated that to metres per second (m/s) and came up with an annual mean wind speed (amws) of around 6m/s. So far, that seems pretty accurate.

Installation

As we are connected to the grid, we decided against storing excess electricity in batteries because they are expensive and bad for the environment. Instead, when it is windy we use our immersion heater to store excess energy as hot water. Normally it is uneconomic to use electricity to produce heat, but with an export price of 1.5p a unit for our surplus electricity (see box left) it makes sense to use it in this way.

The downside to having no batteries is that during a power cut we will not benefit from having our own electricity supply because the whole system will have to be shut down for safety reasons.

Our turbine was installed on 17 December 2010, and so far we’re delighted with it. Despite prolonged periods of high pressure and northerly winds, we’ve exceeded our target of 1096kWh a month. It is especially satisfying to go to bed on a stormy night and know you’ll be making money while you’re asleep.

Carefully planned, small-scale, appropriate technologies, which minimise damage to the environment and benefit everyone seem particularly apt when considering on-farm renewable energy options. Bigger is not necessarily better, especially when a farm is surrounded by beautiful countryside. Renewable energy companies are often keen to promote large-scale projects, but it is the farming family which will have to live with the installation, the neighbours and the bank loan.