6 of Scotland’s best farms – why they stand out

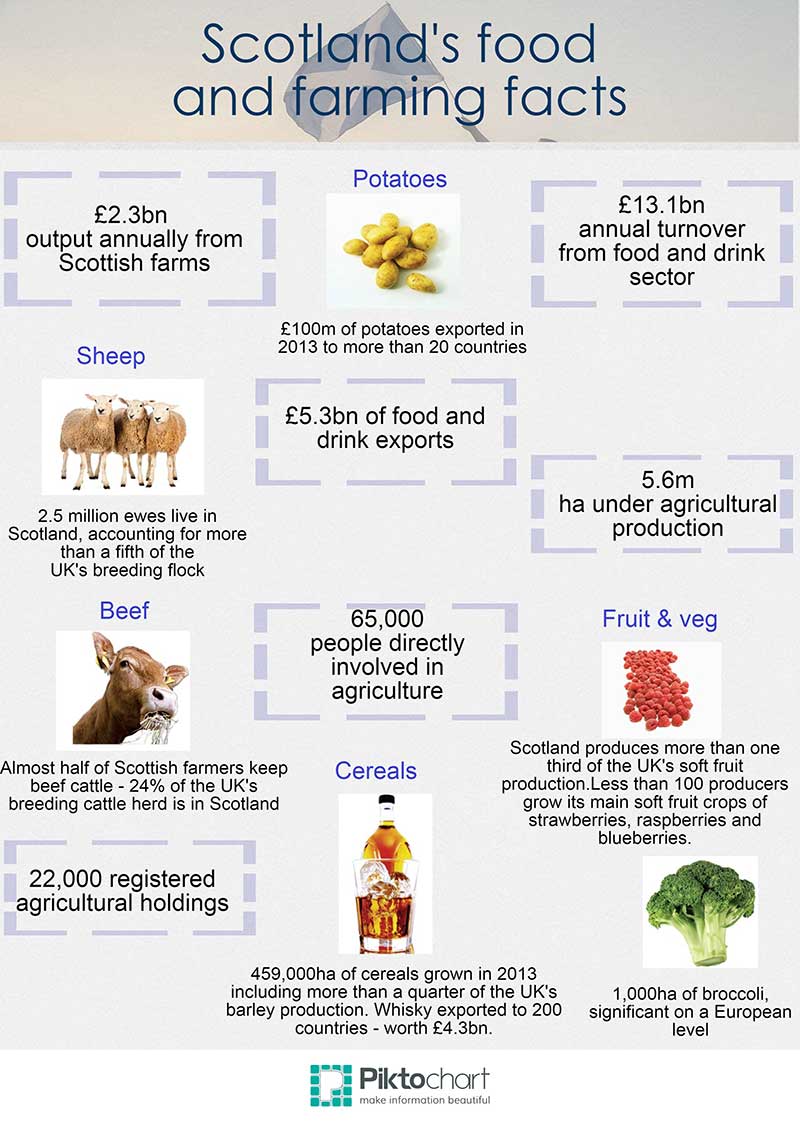

It is home to the famous Aberdeen Angus, one fifth of the UK’s sheep population and one of the UK’s most successful exports – whisky.

Jez Fredenburgh visited six of the best farms to find out why they stand out.

Broccoli and potatoes

Staff management and attention to detail

For Mike McLaren and his family, good people management and early planning are crucial for meeting broccoli and potato orders for UK retailers.

Between Mike, his two brothers, their parents and a team of workers, they farm 1,214ha of owned, rented and contracted land at Cronan Farm near Blairgowrie, Perthshire.

The enterprise includes 304ha of potatoes and 170ha of broccoli, as well as spring barley and winter wheat, 140 suckler cows and 500 sheep.

Broccoli and potatoes are the main income-yielding enterprises and the McLarens don’t leave anything to chance when supplying Sainsbury’s, Morrisons, Tesco, M&S and The Co-operative.

“Attention to detail is very important,” says Mike. “If there’s one thing we home in on its quality to service the market place.”

Every field is tested to match potato variety and soil conditions, while broccoli planting is planned early with grower group East of Scotland Growers (ESG).

All broccoli land is GPS mapped, soil sampled and visited weekly by an ESG crop inspector, while weather stations help monitor conditions and plan jobs such as spraying.

Once ready, broccoli must be harvested by hand within 36 hours, then graded and put into cold storage. An added complication is that crop development and consumer demand are highly weather-dependent. Warm weather quickens the plants’ growth but also decreases consumer demand.

Tight management and regular communication with ESG are key. During harvest, Mike uses a three-week retailer demand forecast from the group and communicates each evening to plan the following day.

“Broccoli is quite management hungry,” says Mike. He spends 50% of his time managing the broccoli enterprise and with 35 pickers, quality controllers, and packers. The labour bill for harvest accounts for 20% of the crop’s costs.

To maintain quality and ease of dispatch, the farm has invested £1.4m in storage including 15,000 potato boxes, a 3,000t potato cold store, and a broccoli store.

The farm uses 600,000kW/year, so £180,000 has been spent on installing 180kW of roof-top solar panels, which will reduce grid energy use by one quarter.

Beef and cereals

Innovation and financial management

The Ivory family’s 918ha beef and arable enterprise is a well-oiled machine where every detail is monitored to ensure top produce and returns.

Profit before interest is budgeted at £240,000 for Strathisla Farms, Perthshire, which also has three holiday cottages.

Adrian Ivory is the first full-time farmer in a family whose members for generations worked in the financial sector. He has tripled the size of the farm since returning from working in London.

“The attitude we have taken to farming is more financially driven than others,” says Adrian’s father Ian.

“We are looking for a profit margin of 2% on land value and 10% of machinery value and we want to keep turnover at more than £200,000/employee.”

Close working relationships with customers, including Asda, and a drive to improve are key to success.

Adrian and his vet, feed company and consultant meet three to four times a year to collectively move the business forward and Adrian opens his accounts to customers so they can set equitable prices.

Adrian’s two pedigree and one commercial beef herd are well-known for their quality and health.

He has a policy of only “investing in the best” when buying pedigree bulls and all calves are rigorously checked to decide which will join the herd. In the 140-head commercial herd, only the top 25 heifers are retained.

Cattle are vaccinated and tested for diseases annually and there is a rigorous isolation policy for animals bought in. The herd’s high health status means that surplus heifers command a premium in the livestock ring.

The family finishes only bull beef after an on-farm experiment comparing the growth rates of bulls and steers.

When left as bulls, 95% were graded U compared to 37% of steers. The bulls took six weeks less to finish and reached a deadweight 90kg better.

“That year with that herd, if I had left all steers as bulls we would have been £20,000 better off – just for leaving their bollocks on,” says Adrian.

Close attention is also paid to consistency and quality in the arable enterprise. About 561ha are owned, but the business contract farms 288ha of cereals and rents 69ha of grass.

The farm has a six-year cropping rotation of potatoes – winter wheat – spring barley – peas – winter wheat – winter barley on the arable land and four years of grass, then spring barley and winter barley on the grassland.

All fields are mapped by the combine and then soil sampled. Both maps are then combined so the farm can achieve a more consistent crop. A drone is used to spot problem areas and report back to the agronomist.

Deer

Finding a niche market and growing it

Red deer farmer and Waitrose supplier Ali Loder is making use of the venison market’s 10-20% annual growth rate.

In the 10 years he has been farming at 87ha Culquoich Farm, near Strathdon, Aberdeenshire, he has grown his herd from 40 hinds to 160 breeding hinds, 10 stags and 122 calves.

Deer farming receives no CAP funding. “It shows there is profitability in [it],” says Mr Loder. “The big problem now is not the demand but the lack of venison.

The farm is part of a Waitrose venison development group, but the retailer has to fill supply gaps with New Zealand venison and only stock some outlets.

“It’s a very fashionable meat and retailers want to secure a reliable supply chain,” says Mr Loder.

Price is negotiated ahead of every season, with this season’s price starting at 529p/kg deadweight and going up 1p/kg each week. A further 5p/kg will be paid for meeting specification.

“Deer farming may seem strange, but the principles are exactly the same as for beef cattle or sheep,” says Mr Loder. Calves winter inside with home-grown silage and grain, while adults live out all year and are fed silage through the winter.

Deer are good at living on marginal land and the Culquoich herd is kept on 22ha of rough grazing and 55ha of improved land.

Input costs are low and Mr Loder is the sole farmworker. Deer tend to stay in good health and he has never had to call the vet. The most significant cost is transporting stags to slaughter in England, which costs Mr Loder £1,600 for 100 animals.

However, a new dedicated deer slaughterhouse is being built to cater for the 100,000 animals slaughtered every year in Scotland. Mr Loder hopes this will further lower his costs.

Sheep

Making the most of the landscape and biodiversity

Paying close attention to natural resources, nutrition and breeding enables John Gordon to get the very best out of his 860 ewes and 220 suckler cows.

His farm, Wellheads, near Huntly, on the edge of the Grampian Mountains, is a 506ha upland unit, which the Gordons have been farming since 1879.

The family is known for producing high-quality livestock and the Charolais cross Limousin steers reach weights of 30kg more on average than other Scottish Charolais when they go to slaughter, growing at a rate of 20g/day faster.

“I’m looking to get the maximum out of what I’ve got,” says Mr Gordon. Making the most of the land and its nutritional quality is a high priority. Although 283ha acres is suitable for ploughing, just 24ha is used to crop barley and swedes to feed the livestock.

As many lambs as possible are finished on grass, while the last 300 are grazed on stubble to finish as quickly as possible and preserve grass for the in-lamb ewes in the spring. John works closely with Willie Thomson, technical director of nutritional advisors Harbro.

Together they analyse and monitor nutrition, including running a mineral forage analysis and benchmarking livestock performance against national data.

“John is a really good farmer, who just doesn’t accept second best,” says Mr Thomson.

The farm’s Blackface ewes are put to Border Leicesters with the best ewe lambs retained as replacements for the main flock of Greyface ewes which are then put to Suffolk and Texel rams.

Continual learning is an important aspect of developing the farm.

Mr Gordon is a member of several sheep farming discussion groups, where he gains tips and experience from others and his son Ewan is off to New Zealand to see what extra knowledge he can bring back to the sheep enterprise.

Neil Wattie and son Mark grow prize-winning Aberdeen Angus with their family

Aberdeen Angus

Quality genetics in a prize-winning herd

Neil Wattie’s farm, Mains of Tonley, is grounded in the history of the famous Aberdeen Angus. The farm was originally part of Tillyfour Farm, where William McCombie pioneered development of the breed.

Mr Wattie, his father, brother-in-law and son have continued developing the genetics of the breed on their 161ha farm and now have a prize-winning herd of 120 pedigree Angus.

In the past few years the farm has moved from producing for the beef market to concentrating on breeding and most of the young cattle are in the top one third of Aberdeen Angus in terms of performance.

“We’ve had quite a bit of success in the last year,” says Neil. Last November the Watties carried off the bull calf, overall calf and male champion prize for a seven-month-old calf at the National Aberdeen Angus calf show.

The herd also produced the female champion at the Stirling bull sales in February, which sold for 8,500 guineas and a champion bull which went for 13,000 guineas.

Success is down to the family’s strict attention to breeding the very best. They started recording performance 10 years ago and have a policy that any animal not up to scratch does not remain in the herd.

“Our aim is to breed high-performance cattle,” says Neil. “We have to try and breed good cattle that are good on the eye but also backed up by good breeding figures.”

The family’s policy is to breed for size but without sacrificing confirmation and calving ease.

When selecting breeding stock, attention is paid to estimated breeding values for calving, milk and muscle, and growth rate.

The aim is for 18-month-old bulls to reach a weight of 1t. Only the best young bulls are kept and the remainder sold as bull beef or steers.

Bulls that are selected for breeding are put on to a high-energy diet of home-grown oats, barley, sugar beet pulp and nutritional supplements.

Cows and heifers are outwintered and fed hay and silage. After weaning, calves are fed a 3kg mix a day of mainly barley and a protein balancer up to 12 months.

Soft fruit

Spotting a seasonal gap and continual, close management

With 4.5m punnets of strawberries, raspberries, blueberries and cherries leaving his farm in a year, Ross Mitchell plays close attention to management and quality control

Castleton Fruit Farm, near Laurencekirk, Aberdeenshire, boasts 89ha of soft fruit polytunnels and Scotland’s first commercial cherry crop. The Mitchells also claim to be the most northerly blueberry growers in the world.

The 287ha arable and fruit farm supplies Marks & Spencer, Asda, Tesco and Sainsbury’s and is run by Ross and his parents, while his wife, Anna, manages the growing 100-seater restaurant and farm shop.

When Ross’s parents bought the farm, it had a dairy herd and 1.6ha of strawberries. But the Mitchells spotted a seasonal gap for supplying soft fruit and began supplying Asda with strawberries.

They now have 45ha, but with UK strawberry sales static for 20 years, they had to look elsewhere to spread their risk and grow the business.

With blueberry demand growing and only 5% of the UK market home-grown, Ross trialled blueberry growing and approached M&S. A close working relationship developed, with M&S requesting cherries soon after.

North-east Scotland’s long cool summers offer perfect growing conditions for filling the August to October soft fruit supply gap between northern and southern hemisphere harvests.

“We have a philosophy to grow premium products and use our geographical location as an advantage,” says Ross.

“[Retailers] don’t want any quality issues – you have to deliver on that,” he says. “[Getting this right] is down to a good harvesting team and a good packing team. People management is crucial – without the people we just couldn’t do the job.”

Six hundred people are employed over the year, mainly in picking and packing across a six-month harvest period. Orders come in daily, so the farm operates seven days a week.

A hot summer boosts consumer demand, calling for careful management of harvest, storage and despatch.

To help achieve this, investment has included a £1.2m packhouse in 2010 with refrigerated storage. Polytunnels, costing £10,000/acre to £12,000/acre, help extend the season and ensure more consistent quality.

Soft fruit is a high turnover, high-risk business so the aim is for a 0-5% profit margin. Labour accounts for 50% of costs with packaging, plants and haulage also representing a high proportion of costs.

As well as picking and packing, labour is needed to construct each polytunnel and plant by hand 1.5m strawberry plants.

The polytunnels help to mitigate risk, as does a computer system, which monitors conditions in the tunnels and soil and automatically administers nutrients and water.

As well as being Leaf Marque accredited, the business must meet each retailer’s standards and cope with unannounced inspections.

The schemes have resulted in 8.5km of hedgerows and 5ha of native trees being planted, two ponds and water margins in all fields.

Sunflowers and other flowering plants around the polytunnels provide bird and insect food while biological controls are used where possible.