How to target worms based on your flock’s worm status

Traditional practices of worming regularly and moving to fresh pasture need to be thrown out the window and replaced with a strategy based on an individual farm’s worm status.

The attitudes of old have been overhauled due to a rapid rise in wormer resistance and now the drive is to preserve existing medicines for future use.

Most farmers have no idea what their resistance status is, says independent sheep vet Paul Roger. “That is coupled with a failure to quarantine stock when they come on to the farm for the first time, or after grazing offlying land.”

Instead of eradicating all worms, producers should aim to retain susceptible strains in refugia on the farm; these are worms that have not been exposed to treatment.

“You want those worms to be predominant, because they are the ones you can manage, and will dilute the effect of any resistant strains,” he says.

| Take-home messages |

|---|

|

Faecal egg count

To identify resistance on a farm, producers should take a faecal egg count (FEC) reduction test, says Mr Roger.

“Take an egg count from separate groups of animals, and dose them each with a different wormer category.

“Later, take another count, to see which wormers have worked – you want at least 95% efficacy.”

Farmers should also use FECs to identify when stock need to be treated, he adds.

“If lambs are failing to reach their target weight gain then worms could be the cause. But only treat those that are worst affected.” Adult sheep rarely need to be treated.

But Mr Rogers says there’s a balance to be found. “Lambs’ natural immunity kicks in at four to six months old, so they need exposure to a light worm burden to help develop that immunity.”

But nematodirus is one species farmers shouldn’t wait to pick up in a FEC, warns Mr Roger. “You have to treat as the risk period arises in early spring.”

Sheep scab is another complication, as farmers are using endectocides – a nematode treatment – in preference to dipping.

“I would far rather see proper use of dips and oral products than showers, which are potentially toxic and ineffective,” he adds.

| Key stumbling blocks when using wormers |

|---|

|

Dosing

Although resistance is not yet a great problem in cattle, producers must apply the same principles as the sheep industry, says Tim Potter from Westpoint Vets.

“It’s much easier to prevent resistance developing than it is to manage it.” One of the biggest problems is underdosing.

“It really is a false economy. And there is a huge difference between resistance and treatment failure due to user error,” he says.

Producers should rotate wormer types, to reduce the chance of resistance build-up. And be aware that younger cattle are most at risk during their first and second grazing seasons – after that they tend to develop some immunity.

But there is no natural immunity to fluke, which is affecting more and more farms across the country, says Mr Potter. Symptoms include weight loss, reduced milk yields and slow growth rates. Fluke may also be identified at slaughter.

Flukicides are specific to different stages of the fluke lifecycle, so timing is important, as are milk withdrawal periods. “Take steps to reduce possible habitats for the host snails, by draining land or fencing off wet areas,” Mr Potter says.

Lynsey Awde, Cumbria

Lynsey Awde has dairy and beef cattle at Broadmeadows Farm, Melmerby, Cumbria, and until recently used a pre-turnout worm bolus on most stock.

“We keep all our own stock, and the farm is quite spread out, so it’s just easy to bolus them,” she says.

“Unfortunately, the cost of boluses is just too high now, so last year we just gave them to bullocks grazing less favoured area ground.”

At the same time, Miss Awde took part in a faecal egg counting trial, and was surprised at how low the worm burden was.

“We’ve really been overdosing our stock. Before, when the odd animal didn’t thrive we’d just worm it, but looking at the egg counts they were absolutely fine.”

Fluke is a big problem on the farm, so Miss Awde routinely treats everything with a flukicide. “We just want to keep on top of it, and try not to overstock land, to avoid poaching it.”

To reduce costs, she has tried a few different products, including drench and injections. “But every year is different, and nutrition and diseases are all linked, so it’s hard to know what’s best,” she adds.

“I wouldn’t want to cut back too far on medicine use, because it could be detrimental to the animal. We’re always trying to find the right balance and we’ll keep on doing the FEC as part of that.”

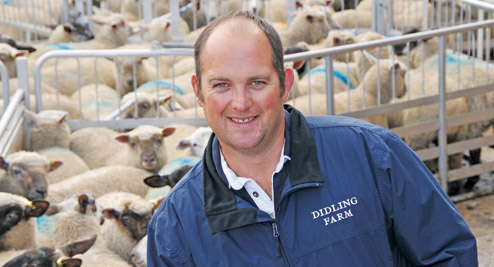

Matthew Blyth, Midhurst, Sussex

Matthew Blyth manages 1,000 ewes and 500 replacements at Didling Farm, Midhurst, Sussex, and has been taking part in a parasite control study since 2007.

Running mostly Lleyn cross Aberfield ewes, Mr Blyth was struggling with high losses and poor growth rates. After carrying out a FEC test, he discovered extremely high levels of haemonchus and resistance to benzimidazole, levamisole, and ivermectin.

“We had pasteurella linked to poor nutrition – and it turns out that was because of resistant haemonchus,” says Mr Blyth. “I was very surprised: I was expecting some resistance, but not that much.”

Following a review of the farm’s worming strategy, he now carries out regular FECs and monitors growth rates using electronic identification.

“We use an autodrafter to batch sheep into weight ranges, which makes worm dosing easier,” he says. “After weaning we leave the top 10% in a group untreated, and just keep monitoring them.”

Mr Blyth has also added chicory to grass leys to support natural immunity, and is rotating leys to reduce the risk to youngstock.

“But I’m surprised by how many worms were on new pasture that was grazed in the autumn by ewes. When we turned lambs on to it last spring it had the highest levels of nematodirus anywhere on the farm.” As a result, growth rates fell from a target of 250g a day to 170g. But other changes are working well.

“We dose 90% of the ewes at lambing time, when they’re at their lowest ebb, and give the lambs a white wormer, when they’re about six weeks old, against nematodirus,” he says.

“Then we use yellow or clear drenches later in the season as needed. We’re also considering using the new dual-active wormer. We aren’t really using less wormer, we’re just targeting it more effectively.”

As a result, growth rates are better and Mr Blyth is able to finish his lambs earlier. “We were selling in January and February – now we’re drafting from June onwards.”

Mr Blyth says wormer resistance is of significant concern to his business because of the big impact worms have on productivity. “If we don’t manage them correctly there won’t be profitable sheep farming in the future,” he says.