Alternative ways to market your milk

Tough times for dairy farms mean many might consider new ways to make a margin. Jez Fredenburgh speaks to producers who have developed alternative ways to market their milk

Tight margins and rising costs are familiar features of dairy farming, but 2012 saw the most difficult year for many milk producers in a long time. There are indications the landscape is improving, but what can farmers do to add value to their product?

Year after year, more branded dairy products appear on retailers’ shelves, each with its own market. Farmers who supply milk to the big processors may feel removed from the end product, but it is possible for producers to tap into these markets themselves by creating a new product, or selling direct to the customer.

“We’ve had a renaissance in dairy products over the past few years,” says John Allen, dairy advisor at Kite Consulting.

Supermarkets have demanded different products and niche markets such as organic have developed, but it’s a competitive market.

“You need a lot of enthusiasm and hard work to succeed. It’s about channelling that and being realistic,” says Mr Allen.

Many dairy farmers have developed new products, found their niche and added value to their milk successfully, but creating a new product “mustn’t be seen as silver bullet”, warns Simon Haley, a rural business adviser at Reading Agricultural Consultants.

“Ninety-five percent of a dairy farm’s income comes from getting cows milked efficiently,” he says.

DairyCo senior advisor Patty Clayton tells farmers to look at their milk contract to make sure they are receiving the highest possible price before considering alternative marketing routes.

“Make use of the bonuses available by meeting the requirements of your buyer, while ensuring your milk is not penalised for reduced quality.

“Reap bonuses on top of your base price through changing the profile of milk production or adjusting feeding and housing.”

If developing a new product is still your aim, the first thing to do, advises Mr Allen, is conduct market research. Look at different products, gaps in the market, competitors and whether your location is an issue, and go on courses to see if the product interests you.

“Once you have identified a product, you need a robust business plan, which includes start-up costs and seeing if you have a strong story to market,” he says.

Costs to consider include labour, planning permission, marketing, getting facilities to meet food standards, building conversions, and equipment. Even basic equipment such as a pasteuriser may cost £10,000-20,000 says Mr Allen.

“Typically, you would aim to invest in year one, break even in year two, and profit by year three,” he says.

Finding financing is another important factor, says Mr Haley, who warns that Rural Development Programme for England grants run out this year.

Instead, he advises seeking out general business grants.

To find your market and be competitive, Mrs Clayton says it is important to find a niche by developing a unique product. Building a brand is expensive but vital in order to differentiate a product. “A margin is often dependent on how well a product is marketed,” she says.

Oaklands Farm, North Wales

Xcel Milk

George White, owner of GLW Feeds, and “frustrated dairy farmer”, runs 200ha in Derbyshire, including 50ha of oat silage and 30ha of maize for his 400 Jerseys and followers. The farm has a dairy manager, arable manager, and a small team of dairy workers. Xcel Milk is situated on the farm and is managed by Jenny Forrester.

Xcel Milk is a new sports drink, developed to rehydrate and reduce muscle damage after exercise. It is made in strawberry, chocolate and lime flavours.

“It’s unique in the sports drink market because it’s made with fresh milk and natural ingredients,” says manager Jenny Forrester. “Milk from the farm is skimmed, mixed with ingredients, including proteins and carbohydrates, then pasteurised, chilled, and pumped to the filling line for bottling,” she says.

Chiller boxes are used for distribution via courier.

“I could see the dairy industry had to change and market milk differently,” says GLW Feeds owner George White.

“Jersey milk is normally a direct route to the fat market, but because of its quality I wanted to explore whether there was an extra value using the skimmed milk,” he says.

Mr White carried out product research and met sports nutrition expert Prof Ron Maughan at Loughborough University.

“I went to see him and he showed me research results showing milk’s ability to rehydrate and rebuild muscle,” says Mr White. They joined forces and Prof Maughan developed the Xcel Milk formula.

“We had all sorts of fun coming up with flavours,” says Mr White. “To start with, we mixed up ingredients and asked students at the university to try them.” Placement students investigated shelf life, separation issues and flavour levels.

Harper Adams graduate Miss Forrester came on board and led the factory build, brand development and marketing over 2012. Developing the formula, bottle design, branding and factory took two years.

The drink is aimed at the professional and serious amateur sports person and the business is negotiating with several professional teams and bodies. The drink will retail through Xcel Milk’s online shop at £2.99 in 500ml bottles. Most of the firm’s UHT equivalent competitors sell at the same price but in 330ml bottles.

“We have positioned ourselves in the mid-price point,” says Miss Forrester.

The company is in the process of gaining accreditation from Informed Sport, which will give assurance that drinks have been manufactured to a high quality and are free from banned sports enhancements.

Because the product is manufactured fully on site, the firm is able to have its manufacturing facilities, processes and ingredients certified, rather than paying £450 for every batch to be tested. Since the product has a shorter shelf life than its UHT counterparts, batches are smaller, which means batch testing would be more expensive for Xcel Milk than for UHT competitors.

Initial accreditation costs £6,000, plus an additional £800 for an annual licence, which has to be reviewed twice a year by Informed Sports.

Every batch of ingredients is tested at a cost of £350-400, so the company tries to buy in large batches to keep costs down. Testing costs fall once the site is fully accredited. While not compulsory, Xcel Milk batch tests its end product monthly to ensure quality.

Four shareholders and a small bank loan have financed the product and business development, including the factory, which is built to process 10,000 litres of milk a day, although not all is intended for Xcel Milk. It takes two staff to run and equipment includes a centrifuge, heat exchangers, holding tanks and mixing tanks.

As sales grow, more of the farm’s milk will be diverted from its current contract to Xcel Milk – something made possible by a good relationship with the farm’s milk buyer.

To raise awareness Miss Forrester has been using social media after discovering a large community of sports people online.

Recently England rugby centre Ryan Atkins tweeted about the product. Miss Forrester has also contacted sports nutritionists, elite athletes, and premiership football and rugby clubs.

Market testing included taking the product to the Olympic swimming team.

To develop the branding, members of the team looked at competitors and took the things they liked from rival products. Their bottle is their own design with special sports grips.

“The East Midlands Food and Drink Forum have been very helpful with developments and advice as well as local environmental health officers,” says Miss Forrester.

“The biggest challenge has been ensuring we could adhere to the Informed Sport standards.

“Doing something different can be challenging because there’s no single resource to ask questions or gain advice from.”

It is vital to have confidence in your product, she says.

Profitable sales are the biggest challenge to any business, says Mr White.

“You’re only here once, so if you want to try something, do it now, not in 10 years.”

Fen Farm, Norfolk-Suffok borders

Raw milk vending

Fen Farm on the Norfolk-Suffolk border is one of the few dairies in the country to sell unpasteurised milk through a milk vending machine. Jonathan Crickmore, his father Graham, and five farmworkers, run its 360ha, and milk 200 Holsteins and 70 Montbeliardes. Mr Crickmore’s wife Dulcie leads the marketing and branding.

Fen Farm’s milk is a “bit sweeter than usual”, says Jonathan Crickmore, with customers saying it “tastes just as milk used to”.

The milk is sold raw through a vending machine in a cow-print shed. Customers can bring their own bottles to fill, or buy one designed by Dulcie Crickmore.

Two years ago Fen Farm sold all its milk through contracts. “We wanted to take control of the price we were getting, and people were always saying they remembered how milk used to taste. So we came up with the idea of selling direct,” says Mr Crickmore.

The farm is on a busy commuter road, so the couple erected a wooden shed, painted it with a black and white cow print, and started bottling and selling the milk from a fridge with a collection box.

The unusual shed attracted curious commuters and word soon spread so that filling the bottles became time consuming. This, and thefts, prompted the Crickmores to swap the collection box for a milk vending machine.

“The machine is one of only four in the UK, although there are thousands on the Continent,” says Tommy Szebeni from The Milk Station Company, which supplied the machine.

Fen Farm’s machine is made of stainless steel and holds 200 litres. It’s filled with fresh milk every other day during the week and every day at weekends.

Sales have risen from 10 litres on their first day of trading, to 150 litres a day at the weekend, and 70-100 litres/day during the week.

“Everyone of every age seems to like the milk,” says Mr Crickmore. “Kids love it because of its sweetness, older people because it reminds them of their childhood, and other people are interested in its health benefits.”

The milk retails at £1 a litre, and the reusable 1 litre bottles, which are bought in for £1, at £1.50 each. The vending machine costs £7,000, and the shed, which was built by a carpenter friend and decorated by Mrs Crickmore, approximately £1,000 including paint. All of the raw milk investment came from the farm business. The raw milk enterprise broke even and started seeing a return on investment after approximately 18 months.

Less than one-thirtieth of the farm’s milk is sold direct to customers – the majority goes to Arla and Dairy Crest – but Mr Crickmore is hoping to expand the raw milk business and is branching into unpasteurised cheese.

The quirky shed has been an important marketing tool from the beginning. “I looked at what other farmers were doing and decided it had to look funky and stand out,” says Mrs Crickmore. Once word spread about the cow print shed and vending machine, Mrs Crickmore contacted journalists and secured local coverage. The farm also uses Twitter and Facebook to reach new and existing customers.

Mrs Crickmore says customers like the quirky branding, which is reflected in the shed, signs, and bottle labels that a friend designed. They also engage customers by being open and informative, such as a blackboard in the shed with information about the farm, raw milk, and useful websites.

“To sell raw milk you have to be really careful with hygiene,” says Mr Crickmore. “I’m always thinking about ways to keep my cows really clean.

“You have to jump through a few hoops initially to sell raw milk legally from the farmgate,” says Mrs Crickmore. “First, you have to work hard at cleaning up your milking practices to the point where your cell counts and bactoscans are almost nonexistent.”

The milk must pass two tests for pathogens, each costing £65, then be tested quarterly. Regulations require a farm to stop selling immediately if it fails a test, then two tests in a row must be passed. Farms in TB areas are not permitted to sell raw milk and those in non-TB areas that want to sell raw milk must have their entire herd tested annually for TB. Fen Farm also undergoes a dairy hygiene inspection every six months, an environmental health officer inspection and must have a hazard analysis and critical control points plan.

“Despite all the work involved there’s a massive enjoyment seeing people enjoying your milk,” says Mr Crickmore. The couple say for them, the hoop jumping is worthwhile, since they are expanding into the raw cheese market.

“If you want to sell great raw milk, make sure the first priority is the welfare of your cows,” says Mrs Crickmore. “Keep your marketing friendly, open and honest – people aren’t stupid and they want information.

“Tell people what makes your farm different, and be open about your practices and values.”

Goodwood Estate, West Sussex

Goodwood Cheese Board

Farm manager Tim Hassell, 11 farm and dairy staff, and a marketing and operations team, work on one of the largest organic lowland farms in the UK. The 1,400ha farm is part of the Earl of March’s 4,800ha Goodwood Estate in West Sussex. It has 180 Shorthorn dairy cows, 40 sucklers, 500 beef cattle, 1,200 ewes, 30 sows, and 240ha of oats wheat, and barley.

The Goodwood Cheese Board comprises Charlton (a hard cheese), Levin Down (a soft white mould) and Molecomb (a soft blue). All are hand-made.

“The pasteurisation, cheesemaking, wrapping, labelling, and boxing, is done on site and distributed via the estate’s wholesale business,” explains Lizzie Vinnicombe, the farm’s operations manager.

When farm manager Mr Hassell joined Goodwood five years ago, the dairy was bottling and selling its milk direct. “Customers said how good it was, so we wanted to move to the next level,” says Mr Hassell. “We already had pasteurisation facilities, so the next step was to build a cheese room. We looked at the estate’s internal market to see how much cheese was consumed, talked to the chefs, and identified varieties that were missing regionally.”

He worked with Smith’s Gore to develop the idea and secured an EU grant, which, with capital investment from the estate, built the cheese room. An experienced cheesemaker was employed to kick-start things and a year after the initial idea, the cheeses were launched. Three years later, 10% of the farm’s milk is now made into cheese – approximately 100,000 litres a year.

Being part of Goodwood has marketing advantages – it is an established brand, and the estate provides an internal market of cafés, hotels, farm shops, and sporting and entertainment events.

“Half our cheese is sold internally and half to the local external market, but this changes during the event season when larger quantities are sold internally,” says Miss Vinnicombe.

“A core, loyal, local customer base that comes every week, is key to sales. It’s important to build a relationship with regular customers, to know their names, have a chat, and run tasters,” she adds.

Cheese sales have doubled year on year from 3t in 2011, to 6t last year, says Mr Hassell. He anticipates by year three the enterprise will be turning a small profit. The profit generated in years four and five will pay for the first two years, he says.

“Processing our milk into cheese will definitely have improved margins,” he says. “If we produced milk just for the main market place, we would be under a lot of extra pressure.”

The cheese room and equipment investment totalled £100,000 and included the building, cheese vat, moulds, and press plus chilling facilities, label gun and packaging materials. Running costs include wages for a full time cheesemaker.

“We have a strong story to tell,” says Miss Vinnicombe.

“The distance from cow to farm shop is small and a big selling point.” Having other farm products to market the cheese alongside, including lager, veal and raw milk, adds marketing value.

The marketing team is proactive, says Miss Vinnicombe: “We’ve had editorials and features, we make the most of the website, run tastings and pitch to potential new business customers.

“We make use of events on the estate and are planning a cheese taster with racing day.”

Environmental health officers license the premises through an annual inspection, but the dairy also has to send cheese samples for bacterial lab testing.

“Each test costs around £17,” says Mr Hassell.

“It can be an expensive start-up cost as each batch has to be tested to start with.” The dairy is also required to have an updated hazard analysis and critical control points plan (HACCP) document.

Village Dairy, North Wales

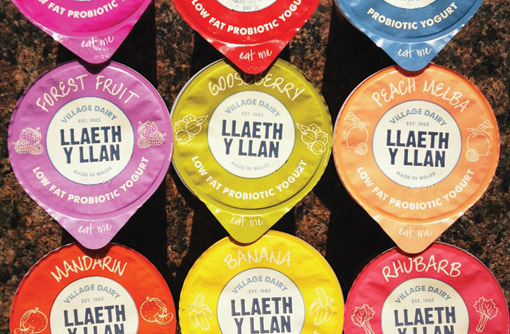

Village Dairy Yoghurt

Gareth and Falmai Roberts have produced yoghurt from their 20ha farm in north Wales since the 1980s. They sell a range of yoghurts across Wales and the West Country. The success of the dairy has enabled their son Owain and daughter Llior Radford to join the company

Village Dairy produces 13 flavours of yoghurt in 450g and 125g pots, including peach melba, gooseberry, and toffee. The yoghurts were originally made using only milk from the farm, but today the milk is bought from other local Welsh farms. The dairy processes all the milk on farm, packs and distributes it.

“We didn’t start off thinking we’d go into yoghurt,” says Gareth Roberts. “None of it was really planned.”

Circumstance and adaptation to what Mr Roberts calls “farmgate threats” led him and his wife to add value over the years through raw, pasteurised, skimmed and semi-skimmed milk, and eventually a successful cream business. But this produced a surplus of milk, which led them to experiment with yoghurt.

“We couldn’t afford an incubator, so we started with a bucket in an airing cupboard,” says Mr Roberts. “We had been reactive to the market up until then, so we had to learn to be proactive.” Mr Roberts conducted market research asking his milk round customers to identity popular fruit yoghurts. After experimenting with formulas, the dairy launched strawberry, raspberry and black cherry flavours.

“We are lucky there’s pressure on retailers in Wales to take on more Welsh products,” says Mr Roberts. “So we got into supermarkets by the back door in about 1998. Once we were in, it grew through north Wales until another retailer placed us into south Wales.”

Village Dairy Yoghurt launched in 1985 with five employees producing 5t of yoghurt a week for a local market. Now it processes 35t a week, and sells more than 7m pots annually to Tesco, Asda, Morrisons, the Co-op, Waitrose, large wholesalers, small independents and catering outlets.

“We’ve had a steady growth year on year and now employ 25 people,” says Mr Roberts. Despite growth, he says the margins are not large: “Profitability per litre of milk is much better when processed into yoghurt, but labour, running costs and raw material inflation is a constant struggle.”

The dairy cost £500,000 to take from micro to commercial scale in 1995 with the help of a 30% grant from the Welsh Assembly. Running costs include wages for 25 employees, a large electricity bill, plus distribution costs. “We are constantly looking at ways to keep running and energy costs down,” says daughter Llior Radford.

Mr and Mrs Roberts and their son Owain developed a quality yoghurt, but had struggled to market it until the couple’s daughter joined the business two years ago.

“Llior is marketing savvy and has completely changed the business – it is now a lot more commercial. She has doubled sales figures,” says Mr Roberts.

Using her experience of working for a large clothes buyer, Mrs Radford overhauled the marketing and led a rebrand. “I implemented what I had learned working for River Island in London, about budgets, new markets, product development and how to react to retailers.

“You have to play the big boys’ game. The less work the buyer has to do for your company, the better. Everything has to run like clockwork and you need to provide information like your year-on-year growth,” says Mrs Radford.

Other marketing-based decisions have included keeping production on the farm despite infrastructure difficulties, and going into renewable energy, to maintain and add value to the brand.

The dairy follows the British Retail Consortium global standard certificate, which is necessary to trade with major retailers. “You have to follow it to ensure full traceability,” explains Mrs Radford. The business also follows HACCP regulations and product recall procedures.

“You’ve got to get business plans down on paper early on and you’ve got to do your homework,” says Mr Roberts. “You need a commercial understanding, but to rationalise this to focus on what is possible without compromising your product.”

Good marketing, adds Mrs Radford, is “not about reinventing the wheel”.

“Changing to fit the needs of retailers is hard,” says Mrs Radford. “You always have to think ahead. It might be logistics or a new procedure they require you to follow, at a cost to your business – not just the constant development of the end product.

“We can never understand and find out the specific retailers’ needs quick enough, as the resources and finances aren’t there within a small supplier, so it’s a constant juggling act. The continual change in retailer buying teams also means you can never create a strong relationship with a buyer,” she adds.

Keep up with the latest dairy news