Stay alert to avian influenza threat warning

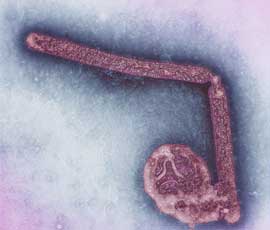

Early detection and preparedness are the keys to the effective control of avian influenza, following the recent emergence of the new H7N9 strain of the disease in China, which has so far killed six people.

“Every egg producing country has to be asking, are we prepared for the next epidemic,” Tjeerd Kimman of the Dutch Central Veterinary Institute told this week’s International Egg Commission conference in Madrid.

He advised industry representatives to “prepare for the unexpected”. “A couple of weeks ago if anyone had said that a low pathogenic strain of AI could kill humans, no one would have believed it.”

One of the problems with any outbreak of AI was that the virus continued to change during the course of the event, he said. That has been the case in the 2003 outbreak in the Netherlands, which had affected over a third of the Dutch industry and led to the death of a poultry vet.

“The virus strain that was isolated from the one person that got killed during the outbreak carried a single amino acid mutation that makes that virus dangerous for humans,” Mr Kimman explained.

“The same mutation found in that strain has now been identified in China. It is a scary situation, because the outbreak strain as far as we know is low pathogenic for poultry, but poses a high risk for humans.”

Vaccination could form part of the defence strategy, said Mr Kimman, but was not without its problems. “Vaccination may reduce virus transmission, and it may help build disease control. But it is also clear that vaccination may mask infection and may interfere with diagnosis.”

The particular challenge was finding a way of differentiating between antibodies resulting from live vaccine and those derived from actual infection.

It was also the case that outbreaks where vaccination had been used had lasted much longer than other outbreaks which had used traditional stamping out.

Furthermore, vaccines had to be applied to birds individually, as it was not possible to treat with water-borne or spray vaccines.

Mr Kimman said the Dutch had learned a great deal from their outbreak of H7N7 a decade ago. This included the fact that Mallard ducks posed a particular risk, showing few signs of AI, but shedding the virus profusely in their faeces.

Free-range systems were also 11 times more likely to succumb to the disease than indoor systems, and wind was a primary form of transmission.

Overall, the 2003 outbreak of AI in Holland had led to the culling of 1,255 flocks, of which 255 were positive for the disease. The financial cost came to over E1bn, over 31 million birds were culled, 453 humans complained about symptoms and one vet died.

China on alert

China has been very efficient at alerting the authorities about the emergence of H7N9 avian flu, and taking steps to contain it. “H7 strains are very unstable and this virus is showing low pathogenicity,” said Dr Alejando Thiermann of the OIE (World Organisation for Animal Health). “It does not cause a major problem in chickens, which makes testing even harder as we do not see lots of dead birds.

“So far there is no evidence of human to human transmission, so it seems most likely that the humans acquired it from the bird.”

For more coverage from the International Egg Commission Conference see the May edition of Poultry World. You can subscribe here