Why Scots regen grower is first Carbon Farmer of the Year

Cattle on multispecies summer cover crop © Doug Christie

Cattle on multispecies summer cover crop © Doug Christie Incremental changes made over more than 20 years to address greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and increase soil carbon sequestration have resulted in Doug Christie from Scotland being crowned the first Carbon Farmer of the Year.

Recognised by the judges for his dogged determination to find ways to do things differently, Doug was announced as the inaugural winner at Farm Carbon Toolkit’s annual field day, held in Oxfordshire earlier this month.

See also: Farmers Weekly Awards 2023: Arable Farmer of the Year

The competition aims to highlight and champion those farmers who are leading the way in adopting farming practices that reduce farm emissions, while optimising output.

According to the organisers, it was a close-run contest, with all the finalists already running carbon-neutral businesses.

Doug, from Durie Farms in Leven, Fife, started to change his farming practices in 2000, having been alarmed by the rising costs of his system and the amount of time spent sitting on a tractor.

Soil health

Farming 570ha, of which two-thirds is in arable production, he initially moved to very shallow tillage when he gave up ploughing on the conventional land and put the focus on soil health.

That has since evolved into direct drilling and a fully regenerative system, which has changed over time with “plenty of mistakes being made” along the way.

“I started by drilling oilseed rape straight into a chopped winter barley stubble with a Krause double-disc drill,” he recalls.

“It’s taken blood, sweat and tears to get to where we are now, but organic matter levels have risen and soils are functioning well.”

Membership of farmer organisation Base-UK has helped him overcome some of the challenges encountered along the way, by sharing his experiences and learning from others, as there was very little guidance available when he began.

Winter cover crop doing its magic © Doug Christie

Living roots

A very diverse and flexible rotation, which is dominated by spring cropping, is now in place at Durie Farms.

Multispecies cover crops are grown before every spring crop, while companion crops also feature widely, so that he makes maximum use of living roots and photosynthesis.

“I’ve tried most things – oats and beans worked well, barley and peas were OK,” says Doug.

Legumes and perennials have been introduced for their nitrogen-fixing and soil health benefits, with spring barley crops being undersown.

“Crops such as spring beans and linseed are tricky in Scotland – in some years we aren’t harvesting them until November.

“Having the diversity means that the whole farming system is interlinked when it comes to carbon. Photosynthesis is where it all starts.”

Farm Carbon Toolkit verdict

Commenting on the winner, Farm Carbon Toolkit’s chief executive Liz Bowles says that Doug Christie’s long list of farm practice changes was very impressive, but having altered his farming system considerably, he is also making good use of technologies to monitor progress.

“He’s not stopping there. Looking ahead, Doug plans to develop agroforestry on some of the permanent pasture and bring diverse leys into his arable rotation.

“His work started in 1999 and he is a real pioneer – a very worthy winner.”

Input use

A spin-off is that there’s been a reduction in artificial input use, most of which are highly embedded carbon products, he points out.

Fertiliser purchases are now one-third of what they were, while other inputs such as insecticides have been eliminated.

Fuel use is coming down, but the Scottish climate can interfere with Doug’s plan.

“Drying is the biggest cost per hectare – we can use 60 litres/ha on drying. That’s an area I would like to improve on.”

Otherwise, he uses 45-50 litres/ha for growing a crop on a stubble-to-stubble basis, of which just 5 litres/ha is to establish cover crops that are direct drilled.

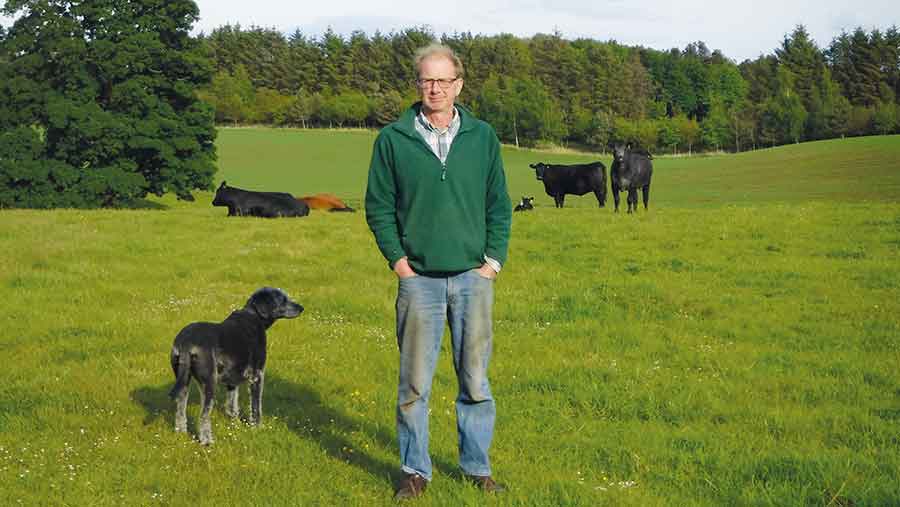

Doug Christie © Doug Christie

Organic beef

The remaining one-third of the farm, which converted to organic in 2006, has a suckler herd, with some organic cereals grown.

Even though he was running an extensive system at that time, the cattle were still responsible for 55 litres/ha of fuel use – all of which went on the feeding and muckspreading operations.

“I changed to adaptive multi-paddock grazing, which has reduced that to 30-35 litres/ha and also helped to sequester more soil carbon. It’s been better for the soils and better for the cattle.”

Despite the progress made, Doug has not traded any carbon to date.

“Carbon payments are based on additionality, so it seems that a degraded farm would have more to gain than one that has been doing all the right things for a long time.”

Farm Carbon Toolkit will be holding a farm walk at Doug Christie’s farm on 21 November from 1pm-4pm

Other Carbon Farmer of the Year finalists

1. Craig Livingstone, Lockerley Estate and Preston Farms, Hampshire

Craig describes his experience as being on a journey.

With estate owners who are passionate about carbon sequestration, he highlights three key areas when it comes to reducing emissions – personal, operational and organisational.

“On a personal level, you have to be comfortable with it. It’s not a race and hurdles are part of the process,” he notes.

The operational part is the farm’s regenerative system, which has given him significant savings in the carbon budget.

A change in the fuel type used in the grain dryer saved 55t of carbon dioxide, while appropriate use of technology and techniques such as polycropping and understoreys have helped too.

As far as the organisational concept is concerned, Craig says carbon extends beyond the arable land and is in the DNA of everything carried out on the estate.

“That extends to properties and the lightbulbs used in them, for example, as well as to land use.

“So we have solar and energy crops, as well as agri-environment schemes, alongside arable crops.”

2. Anthony Ellis, near Liskeard, Cornwall

Anthony acknowledges his father’s influence on the farm’s approach – he installed a biomass boiler, which runs on oats to heat the house and buildings, and made his own diesel for the farm pickups from fish and chip oil.

“He liked to reuse things. It was the start of things to come.”

The transformation of the remainder of the farm began with strip-tillage and cover cropping, which then saw sheep being introduced.

Land with solar panels is grazed, as are winter cereals and cover crops.

Input use has fallen, with the nitrogen rate dropping from 200kg/ha to 150kg/ha, insecticides have gone and fungicide use is down.

Phosphorus and potassium haven’t been applied for the past three years.

Anthony reports that slug and aphid pressure has subsided as the system has developed and soils have improved.

“There have been lots of small changes that are now bringing big rewards.”