The history of the sugar beet generation

The Cantley sugar beet factory is celebrating its centenary. David Richardson, who’s been involved with the crop all his life, recalls how growing beet has changed over the decades – and considers where now for a crop that remains critical to many arable farmers’ fortunes

When I look back at the amount of back-breaking work the sugar beet crop required when I was a boy, I sometimes wonder why it became so popular.

In those days, it kept thousands of men employed, though workers were only paid a few pounds a week. Yields of 10t/acre of clean beet were seen as satisfactory, with sugar percentages often not much more than 15% – although the standard by which we were paid was 16%, as it is still today.

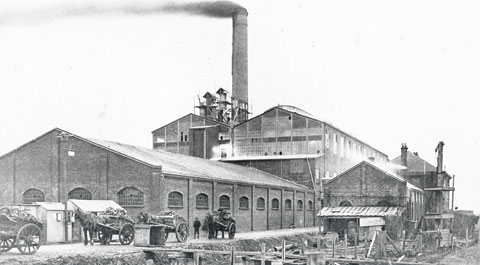

The crop had first come to this country in the early 20th century after a group of Dutch investors began offering contracts to Norfolk farmers to grow it to be shipped to Holland for processing. By 1912, they were satisfied the crop could be grown in this country and built the factory at Cantley.

Terrible floods in Norfolk in 1912 and the disruption of the First World War meant that it wasn’t until the early 1920s that the Dutch-built factory got back into full production. By that time, encouraged by the high price of sugar, further processing factories were built (although some of them failed almost immediately). By 1928 there were a total of 18 operating across the arable areas of the country including one in Fife, Scotland.

Back in Norfolk, the Cantley factory – under the control of Dutchman, Joanness Van Rossum, who had moved to live in Norfolk to supervise the operation – remained the flagship plant. To secure supplies of roots, as well as to demonstrate the opportunities to reluctant Norfolk farmers, he bought several thousand acres of ideal sugar beet land around Cantley. He brought in Dutch farmers to manage these farms and built huge barns in the Dutch style to cover the crops they grew and to stable the many horses used on the land.

But sugar beet did not become a staple crop in Britain’s agricultural economy (and a must-grow crop for most Norfolk farmers) until 1936 when the Sugar Industry Act was passed by Parliament. It provided for the amalgamation of all existing factories into a single corporation in which the government held shares and appointed farmers representatives (among others) to the board with the brief to ensure fair pricing between growers and processors. The company was named The British Sugar Corporation.

Once again war was to intervene. In 1939, under the auspices of the War Agricultural Committees set up by the government in the face of rationing, the aim was to produce as much as possible. The factories also produced large quantities of animal feed in the form of the bi-product, dried sugar beet pulp, which was almost as valuable for livestock back on farms as the sugar was to human consumers. Norfolk farmers at that time produced about one-third of the sugar beet grown in this country – a statistic that has been pretty accurate to this day.

Today, growers on grade 1 land are reporting yields of up 100t/ha or 40t/acre, with sugar contents up to 17% to 18%.

Although those of us on grade 3 land still count ourselves lucky to produce much over 70t/ha, even in a record year like 2011, which is regarded as close to the minimum viable yield at current values.

Unlike cereals, however, sugar beet yields seem to improve a little each year, thanks to the efforts of plant breeders and there is general optimism throughout the industry that they will continue to do so.

Who knows what kind of crop we will have this year? We’ve drilled all our beet earlier than ever before, starting on 29 February, into very dry seed-beds in the hope that enough moisture will fall on them soon to germinate the seed. We drilled almost as early last year and, despite the drought, we got a good crop. But last time we had two such dry years together, in 1975 and 76, the second of those crops was a disaster. One reason for that was that we had no effective way to deal with aphid-borne virus yellows and in the hot dry conditions it decimated the crop and caused sugar shortages. Today we can control such problems much more effectively with chemicals.

Other major advances in growing the crop that have become available over the years are mono-germ seed that is precision drilled according to the plant population desired, eliminating the need for chopping out; rhizomania-tolerant varieties, the yields of which don’t seem to suffer from the debilitating root disease that crossed the Channel from Europe 30 or so years ago; chemical weed control which is expensive but still cheaper than hand-hoeing; and the mechanisation of lifting culminating these days in huge self-propelled six-row tankers that hoover up roots at such speed that the old boys with whom I worked 60 years ago would never believe it. But I do worry what all that weight is doing to the soil structure.

Opportunities missed would include growers’ failure to put together a consortium to buy The British Sugar Corporation when it was on the market 30-odd years ago. Sugar processing in other countries such as Holland and Germany is controlled by grower co-operatives and their returns are usually ahead of British growers. Then again, would British farmers (bearing in mind our poor record of co-operation) have had the courage to rationalise processing into just four factories, as owners, Associated British Foods, has done. Those factories are claimed to be the most efficient in Europe?

The other opportunity that has so far been denied British and European sugar beet growers is our inability because of politics to grow genetically modified sugar beet. Were we able to do so we could save a fortune on chemical sprays to control weeds, grow much “greener” crops and earn better returns while competing with sugar crop growers anywhere. I live in hope that this situation will soon be reversed and we are allowed to start to catch up with the rest of the world.

A year ago most British sugar beet growers were unhappy and ready to give up the crop. Freezing winter temperatures and snow for weeks had caused many to lose tens of thousands of pounds from beet that could not be lifted or processed and were a dead loss.

Twelve months on, growers have just harvested a record crop in weather that could not have made the job easier. What a contrast. The result is a much happier bunch of growers some of whom are even planting extra acres of beet, knowing they will get a slightly lower price for them, for ethanol production. Maybe this is the future. Maybe we will mainly become green fuel growers with sugar for human consumption almost as a bi-product. Maybe. But first let’s see what this year brings.