How a new test helps bean growers tackle stem nematode

© Gary Naylor Photography

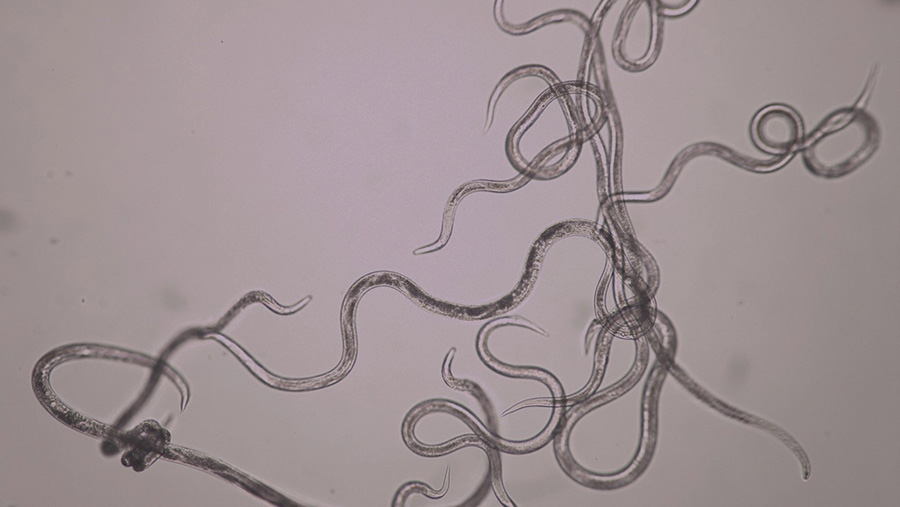

© Gary Naylor Photography A new rapid test that complements existing diagnostics tools to identify both the presence and species of stem nematode in seed and soil will improve decision-making when managing its impact.

Stem nematode has become an increasingly important pest for field bean growers in the UK, with the potentially damaging pest affecting both spring and winter sown crops (see panel).

See also: Maize trials show soil benefits of undersown grass mixes

As there are no chemical means of control in field beans, growers are solely reliant on cultural measures to help protect yield and quality of their crops from the seed- and soil-borne pests.

Stem nematode – key facts

- Stem nematode is the common name for two species of free-living nematode pests found in a range of soil types

- These include Ditylenchus dipsaci (formerly known as the oat/onion race) and Ditylenchus gigas (formerly known as the giant race).

- Both species affect bean crops, but D gigas is by far the most common and damaging, responsible for about 90% of problems seen on UK farms.

- D gigas has a relatively narrow host range, affecting just field and broad beans and several weed species, but for D dipsaci the host range is much wider, numbering more than 450 crops and weeds. It includes alliums such as onions and leeks, peas, oats, potatoes, lucerne, ornamental bulbs, and a long list of common weeds including mayweed and chickweed.

- The two species are very hardy, being able to endure sub-zero winter temperatures, warm summer soil temperatures of 55C and can survive for years in desiccated form in plant debris, seed, and soil.

- Spread of the pest is largely through infested seed or contaminated soil. The proportion of infested seed samples processed by the PGRO annually varies, with up to 10% infested after a dry spring, like 2020, and can reach up to 20% in wet years.

- Stem nematodes feed within the plant’s stem. Ditylenchus gigas causes individual plants or patches of plants to appear stunted, with stems thickened and twisted. Leaves can also become thickened and brittle, with a bronze discolouration in the petioles. Later on, stems turn brown or rust red and may swell, twist and break. Pod fill is uneven, and pods become black and shrivelled as they mature.

- Yield loss can be considerable – worst recorded cases have seen yield reduced to just 0.8t/ha.

- There is no chemical control, so managing its impact is purely down to using clean seed, plus rotation and adequate weed control to minimise populations building within the soil.

- If D gigas is identified beans should be avoided in the affected fields for 10 years as this can have a high impact on yield and grain quality. If Ditylenchus dipsaci is identified, it is more of a rotational problem affecting beans to a lesser degree but potentially impacting greater on other crops in the rotation.

Seed testing

Testing of seed and taking infested lots out of production to stop spread to clean land has long been a key part of stem nematode management and Pulse levy body the Processors and Growers Research Organisation (PGRO) has provided a seed-testing service.

However, PGRO has now updated its testing offer after developing a molecular stem nematode test that works for both seed and soil samples.

While a standard seed test that checks for the presence or absence of stem nematode will continue to be offered, growers can now request the molecular test to quickly identify which of the two stem nematode species is present.

The same molecular method can also be used for soil samples, with an improved limit of detection over existing diagnostics methods of 10 nematodes/100g of soil.

While soil tests are available at other laboratories, most use morphological techniques – essentially looking down a microscope – to identify nematodes and have a turnaround time of up to three weeks.

Quicker test

This is in contrast to a turnaround time of less than one week for the new molecular test, giving growers and agronomists a much quicker result where required, according to PGRO research and development manager Becky Howard.

She adds that the ability to speciate samples also leads to better management, as the two species have significantly different host ranges. Subsequently, results will help better plan rotations to minimise impact on host crops and build-up of the pest in soils.

“The molecular soil test will be particularly helpful for growers looking to expand their pulse area, or to new growers seeking reassurance about particular fields.

“We recommend that any sampling is carried out in late autumn and early spring when soils contain more moisture, and cores are taken down to at least 25cm, preferably deeper, to increase the accuracy of results,” she explains.

Prices for testing can be seen below and PGRO has fine-tuned its sampling advice for both seed and soil testing to improve the accuracy of detection. More information is available at pgro.org/molecular-testing.

PGRO stem nematode testing |

|

|

Test |

Cost |

|

Standard seed test (presence/absence) |

£33+VAT |

|

Seed test with molecular species ID |

£77+VAT |

|

Molecular soil test* |

£77+VAT |

Biofumigation research

Results from a PhD project at Harper Adams University suggest that biofumigation of soil with brassica crops could help suppress stem nematode numbers before planting beans.

It has long been known that glucosinolates in certain species of brassica, such as Indian mustard, react with myrosinase enzymes in the soil when chopped and incorporated, producing isothiocyanates and other volatile compounds.

Previous research

In previous work at the University, isothiocyanates produced by Indian mustard have been shown to suppress potato cyst nematode (PCN).

In addition, a partial biofumigation effect has also been observed, whereby glucosinolates exuded from growing brassica roots are converted to isothiocyanates by fungi in the soil that secrete the enzyme myrosinase, suppressing nematodes in the root zone.

A recently completed three-year spin-off study aimed to evaluate the potential of biofumigation for suppressing stem nematodes ahead of winter bean crops.

For the study, researcher Nasamu Musa established various brassica species in early August, and these were then chopped and incorporated just before flowering in early October ahead of planting winter beans.

30% reduction

For the less common stem nematode Ditylenchus dipsaci, little difference was seen between the control and brassica treatments, but in Ditylenchus gigas Mr Musa saw a 30% reduction.

In the lab, it was observed that exposure to low concentrations of isothiocyanates also impeded the pest’s ability to find plant hosts, so its overall efficacy in reducing the pest’s impact on crops is perhaps more profound than the headline figure suggests.

Mr Musa says biofumigation could provide a useful component in integrated pest management strategies and hopes future research will enable the isolation and production of the soil fungi converting glucosinolates to isothiocyanates.

“Then we might be able to combine a brassica crop with increased levels of fungi to maximise the biofumigation effect.”

He adds that some brassica species are suitable hosts for D dipsaci, such as white mustard and rocket, so are not recommended in a biofumigation system against stem nematodes.