Tips to help control clubroot in oilseed rape

Perfect conditions last autumn have led to an increase in reported cases of clubroot in oilseed rape and farmers are being warned the yield-slashing disease could become even worse in the future.

Clubroot is caused by the soil-borne fungus Plasmodiophora brassicae and is an extremely persistent pathogen due to its specific lifecycle.

Infection begins when exudates from roots of nearby host plants stimulate resting spores to germinate and produce motile zoospores that swim through soil water and infect root hairs, explains Adas plant pathologist Julie Smith.

See also: How to avoid ‘oilseed rape sickness’ slashing yields

Root cortex infection follows, stimulating cell division and leading to the characteristic galls seen on the roots that obstruct nutrient and water transport leading to plant stunting and yield loss.

“When the galls break down they release resting spores back into the soil. These are very resilient and can remain dormant and viable for about 15 years if a suitable host is not present.”

Weather at sowing

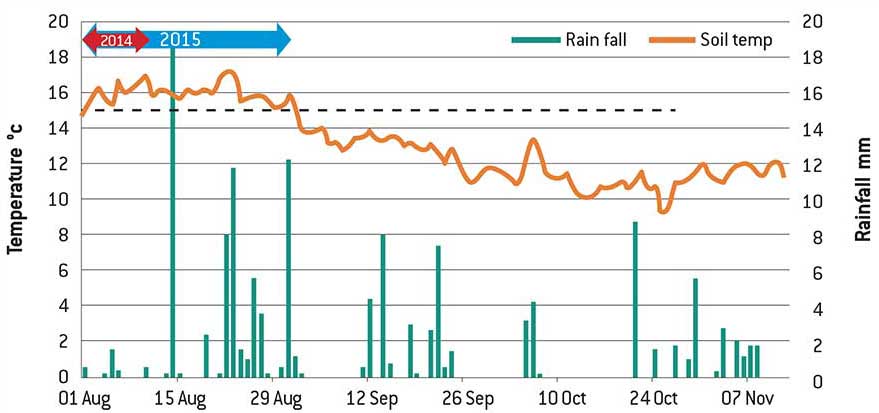

Closer oilseed rape rotations are likely to have exacerbated the disease, but the biggest influence is the weather at sowing. Clubroot has a threshold of 16C and soil has to be wet to enable the movement of the zoospores, Dr Smith says.

The warm, wet conditions across the UK last autumn were ideal and the window for infection was wide (see below), stretching through all of August and into the first week of September.

Conducive weather for clubroot infection in autumn 2015

According to recent climate change modelling predictions carried out by SRUC, larger areas of the UK are likely to become suitable for infection. The clubroot growing season is also likely to be extended, plus more generations of clubroot might be possible in a year, she warns.

Prevention

While there is no specific chemical treatment for clubroot, there are a number of steps growers can take to minimise the effect of the disease. However, prevention is better than cure and keeping the pathogen out of the soil is important, especially if the disease is present elsewhere on the farm or in the area.

This requires growers to be vigilant, checking crops for any sign of the disease, particularly in wet areas as low levels of infection may go unnoticed, says Dr Smith.

Hygiene is very important and growers should take measures to prevent resting spores from being transferred via soil between known infected fields and farms on boots and machinery. Spores can also be spread to clean land through the dumping of infected vegetables or in manure from animals fed on infected produce.

Combined control methods

For growers who have detected clubroot infection, there is no one single effective measure for control, says Dr Smith.

Rotation, liming and the use of resistant varieties are the main options. But addressing drainage and compaction issues, maintaining boron levels and avoiding very early drilling should be considered too.

Growing a clubroot-resistant variety is an important strategy, but the available varieties are not resistant to all the pathotypes of the disease, says Dr Smith.

The current genetic resistance, which is based on a single major gene – the Mendel resistance – could also be quickly eroded in short rotations when there is a build-up of clubroot pathotypes that can overcome it.

“Overreliance on resistant varieties will lead to quick breakdown,” says Dr Smith. Therefore she advises maintaining at least four years between brassica crops.

Liming

Liming is the other main approach to minimise infection by raising the pH and calcium levels in the soil, she says.

“If you can increase pH from 6.5 to 7 there is a benefit in terms of clubroot control, reducing the disease from about 70 to 40% in field trials.”

The severity of the disease has an influence on yield, so for every 10% of plants infected, there is a 0.3t/ha yield loss. Therefore raising the pH can mean quite a big yield saving, she adds.

Liming is recommended by Hereford-based independent agronomist Antony Wade, who has seen new cases of clubroot in four of his client’s fields this year.

“The patches we find are usually low pH and then spread from there.”

Growers have the option to use ground limestone rotationally, or apply a faster-acting product such as LimeX 70 in the autumn to raise the pH quickly ahead of drilling, he explains.

He advises growers to extend the rotation beyond five years if possible and use Mentor, the only resistant variety currently on the AHDB Recommended List.

Controlling cruciferous weeds in the autumn in other crops is also very important as weeds such as volunteer oilseed rape, charlock, runch and hedge mustard act as hosts for the disease and allow the pathogen to cycle, says Mr Wade.

Another aspect to be cautious of is the use of brassica cover crops – they may not show clubroot, but could be hosting it, he warns.

Breeder’s view: Need for better-yielding resistant varieties

The risk of clubroot was highlighted in a visit by Carol Norris, seed development manager at Bayer, to a trial site earlier this year.

She recalls that the host grower had never seen clubroot in his field before, but the field was completely infected except for the trial plot, despite there being no known clubroot resistance in the varieties in the trial.

“We believe the reason was that the trial plot was drilled in dry conditions, while the rest of the field was drilled in wet conditions one week earlier.

“Clearly there is a need to develop better-yielding, more robust clubroot-resistant oilseed rape varieties, and this is certainly on our breeding agenda for the UK. Samples from natural infection sites, such as the one in Kent, will help efforts by informing our breeding team on the exact pathogen behaviour in the UK,” she says.

Cover crops

Matthew Back, who is reading plant nematology at Harper Adams University, has conducted work on cover crops to help determine whether brassica cover crop species would exacerbate or suppress clubroot.

He carried out glasshouse studies where three brassica biofumigant cover crop species were grown in highly infested clubroot soils. He observed their effect on the cover crops themselves and on following oilseed rape plants after the cover crop species were macerated and incorporated into the soil.

The three species investigated were Indian mustard, also known as brown or yellow mustard (Brassica juncea), rocket (Eruca sativa) and oil radish (Rapahanus sativus) – commonly found in cover crop mixes.

“We found the Indian mustard and rocket were both very susceptible to clubroot and expressed high disease severity. The radish had negligible infection.”

In the following oilseed rape plants, the pots that had previously had rocket or Indian mustard exhibited the highest disease severity in the oilseed rape, whereas the radish pots showed no increase or decrease in infection, similar to the untreated pots that had no biofumigants grown.

“The take-home message from these experiments is that if you use Indian mustard and rocket, you potentially could multiply the clubroot inoculum and increase the risk to your following oilseed rape crop.

“Growing an oilseed radish would maintain the status quo, as it does not have a direct effect on clubroot and doesn’t exacerbates the situation,” she says.

Case study: Stretch rotations to fight resistance

Duncan Farms, Turrif, Aberdeenshire

Farm manager Sandy Norrie is very experienced in managing clubroot as the disease is endemic in the soils around the Aberdeen region. This is because turnips have historically been grown for animal feed and brassica vegetables are often present in the rotation.

As a result, clubroot was first observed when rape was introduced into the rotation decades ago, and now two-thirds of the 500ha of oilseed rape grown annually is planted into clubroot-infected land.

Stretching rotations and variety tolerance are Mr Norrie’s main management strategies to combat the disease. Knowing the clubroot status of each field is crucial to ensure the correct variety is selected, as the yield penalty from growing a non-clubroot-tolerant variety on infected land can be up to 3.5t/ha, he explains.

Having grown Mendel and Cracker in the past, Mr Norrie now grows Mentor. “It is a step up in yield, but still a bit off conventional yields.”

Better-yielding varieties are much needed, as Mentor can carry up to a 0.75t/ha yield penalty compared with the farm’s best conventional non-tolerant variety, Anastasia. This makes it difficult to achieve the target of averaging 4.75t/ha across all his rape crops in years when he has a high percentage of rape on clubroot land.

A five-year gap between all rape crops is now common practice on the farm, irrespective of whether the soils are infected or not. Tightening rotations encourage volunteers, which provide a continual host for the clubroot pathogen and increase rape plant populations, altering architecture and ultimately yield.

Mr Norrie also maintains pH levels up to 6.4 through variable-rate application of calcium lime, buthe doesn’t raise the pH higher specifically for clubroot control.

“Applying lime on clubroot land is not cost effective. If we have a pH of 6.3-6.4, we would have to put 15t/ha of lime at £300/ha for one crop in five to benefit. We are not going to get that much return.”

While clubroot itself can’t be mitigated, the crop can be helped by balancing growth regulation and nitrogen. Apply plenty of robust growth regulator to give it strength, and limit nitrogen rates to prevent excessive top growth that the poor root systems can’t support, he explains.

Sandy Norrie © Rhuary Grant