Irregular food supply could be the cause of bee decline

A group of farmers and agronomists are looking to boost bee numbers in a five-year project, by identifying and plugging any gaps in nectar and pollen supply during the season.

Bees are of great importance in the pollination of many crops, and they also greatly enhance the biodiversity of an area by pollinating many other plant species,” says Paul Butler, Gleadell business development manager.

Unfortunately, bee numbers have declined over the past few years, possibly due to a combination of poor weather, inconsistent food sources and the verroa mite, he says.

Hutchinsons environmental services manager Bob Bulmer believes the decline is mainly down to the irregular supply from food sources. “We wanted to look at when food availability was a limiting factor during the year and then identify what steps farmers can take to help increase populations.”

Bee food supply is being investigated in a five-year study, jointly funded by Gleadell Agriculture and the agronomy specialist Hutchinsons. Two growers, Jim and Alex Godfrey in North Lincolnshire and David Felce in Cambridgeshire are taking part.

A key part of this project is quantifying the on-farm food available to bees and the means of doing this came about when examining a number of environmental projects in France.

“We were looking at what the French were doing in their environmental work and we came across a model developed by the co-op Invivo, which predicts food supply for pollinating insects,” explains Dr Bulmer.

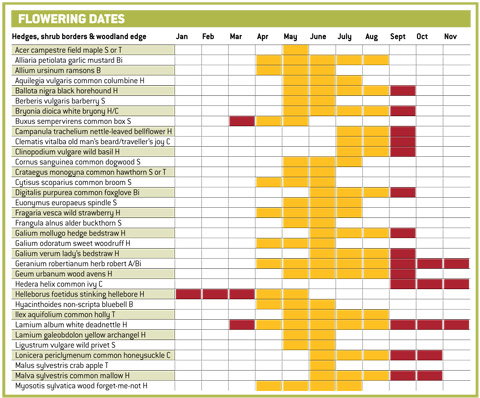

It started in September and October 2011 with a botanist spending a day on each farm looking at what flora were present on the farms in hedgerows, margins, grassland and ditches. The model then predicts pollen and nectar availability for each month of the year.

One of the farms in the project is the Godfrey’s Worlaby Farm. The 565ha being monitored is on chalk wolds, with cropping based on winter wheat, potatoes, vining peas and sugar beet.

The model showed that vining peas were already contributing pollen and nectar in May, while in early spring and October there was very little food.

Dr Bulmer adds that the first year’s results at Worlaby Farm highlight two critical periods where food is in short supply.

“The first is the period before hibernation in September and October, which is critical as they build enough reserves to survive the winter.

“This is particularly important if there is a late spring like this year, where the blackthorn and other early flowering species didn’t flower until May,” says Dr Bulmer.

“The other critical time is early spring in March. The model shows there is an abundance of nectar and pollen in April to August, from existing hedgerows, pulse crops and margins.”

These low points in food supply act as a limit on populations. Therefore, the next stage is to look at cost-effective options using mixtures of cultivated and natural plant species to help fill the gaps.

Jim and Alex Godfrey together with Dr Bulmer and Mr Butler are now considering their options. “It has to be something that is easy to maintain and will survive longer term if we are to encourage farmer uptake,” says Alex.

Bee research

Jim Godfrey became interested in bee populations two to three years ago after seeing a presentation by Christine Tacon, when she was at the co-op, looking at bee numbers and food sources on their farm.

“Results showed that continuity of food source promoted the yield and health of hives. It suggested that the decline in bee numbers may be to do with food supply as well as the varroa mite.”

Options include reviewing the timing and frequency of hedge cutting, to maximise and manipulate the time of flowering.

Alternatively, establishing blackthorn and hazel along woodland edges would also offer early nectar and pollen in March. Also encouraging ivy in woodland is beneficial, being a good food source in late autumn, says Dr Bulmer.

To enable comparisons, they are looking to use another block of land nearby as a control where no changes are being made, so that they can demonstrate any improvements in bee numbers.

Dr Bulmer says they are also looking at methods of monitoring bee number which include sensor-activated video and counting mechanisms such as those used by Rothamsted Research.

Much more work is needed before any recommendations can be made. But one thing is clear, increasing bee numbers is not just a case of establishing more standard pollen and nectar margins, as they often supply bee food when it is already abundant. These mixes need to contain species of early and late flowering plants, which when established, will contribute to the low availability periods of the year.

“It is essential that we provide food sources during these periods to support higher bee populations in the future,” says Dr Bulmer.

Bee decline in UK blamed on intensive farming