Growth in weed and pest resistance spells trouble

A trend towards min-till farming practices, the loss of agrichemicals and climate change will present UK growers with new pest and weed challenges over the coming years.

A study by the Universities of Exeter and Oxford estimate that global warming is resulting in crop pests extending their range by as much as two miles a year. These pests are heading towards the North and South Poles, and are establishing themselves in areas that were once too cold for them to live in.

It is estimated that between 10% and 16% of the world’s crops are lost to disease outbreaks, and the researchers warn that rising global temperatures could make the problem worse.

One example they point to is the Colorado potato beetle. “Warming appears to have allowed it to move northwards through Europe into Finland and Norway, where the cold winters would normally knock the beetle back,” says Dan Bebber from the University of Exeter.

Foreign pest threats

Leafhopper: This pest has become quite prevalent in northern France. It infests mainly wheat, and disease symptoms are similar to barley yellow dwarf virus.

Pollen beetle: Populations in Germany and France have developed resistance to pyrethroids and caused widespread destruction of crops.

Cabbage stem flea beetle: This is another pest known to have built up a tolerance to pyrethroids, which, particularly in Germany, has been affecting oilseed rape crops.

Colorado beetle: There remains a concerted campaign to keep it out.

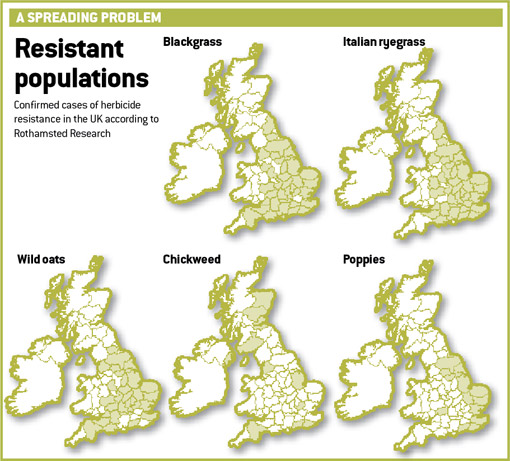

Weeds are spreading too, such as blackgrass moving north into Scotland. But it is not just new weeds and pests, existing populations are developing resistance to available chemistry.

Pests: resistance concerns

Steve Foster at Rothamsted Research points to the control of two aphids whose insecticide resistance profiles are changing. He’s been studying the peach-potato aphid and the grain aphid – the former has now developed resistance to many insecticides including pyrethroids, carbamates and organophosphates.

“Peach-potato aphid is the number one aphid pest in the UK and many parts of the world,” he says. “Some have several types of resistance and there are cases when you just can’t kill them with the compounds available,” he adds.

What could pose a bigger threat to UK growers is if a neonicotinoid-resistant population of the aphid migrates from southern mainland Europe.

“I’m screening samples to monitor the situation for growers and alert the relevant sectors if neonicotinoid-resistant aphids arrive in the UK.”

As the aphid can live on potatoes, sugar beet, lettuce, brassicas, legumes and ornamentals, it is thought that the species’ exposure to a broad range of pesticides is to blame for its ability to resist treatments.

“If each of the crops are being treated with insecticides, the level of selection for resistance is heightened, but there’s also something about this species in that it seems more adaptable to evolving types of resistance.”

Knock-down resistance

A more recent problem that Rothamsted has been alerted to is pyrethroid resistance in grain aphids. Control problems in wheat in 2011 sparked research into the pest’s DNA, which unearthed a mutation that confers knock-down resistance that is known to affect pyrethroids in other pests.

“We’re testing live samples from the field and looking at the aphid’s DNA to ask what proportion of the sample carries the mutation,” Dr Foster said.

“Once we’ve discovered a mechanism and know how to look for it, we will be able to advise growers how things are changing in terms of prevalence or potency.”

Steve Ellis from ADAS believes saddle gall midge is re-emerging as a potential problem for growers.

ADAS scientists have just completed their first year of research for the HGCA after reports of significant yield loss and limited treatment options.

“Part of the project involves monitoring saddle gall midge development in the soil at two sites and recording weather data over the same period. Ultimately the aim is to develop a model that will allow us to better predict the timing of midge emergence to enable precise insecticide application.”

At a Buckinghamshire monitoring site, about 150/sq m saddle gall midge larvae were found – much lower than counts in 2012 when more than 1,000/sq m were recorded. At a sister site in Yorkshire there were similar numbers, but the larvae appeared to have been attacked by a parasitic fungus.

“Although midge levels at the monitoring sites were not as high as might have been expected, we have had reports from sites in Suffolk and Scotland where pest numbers were very high and a significant impact on crop yield was expected.”

Dr Ellis is keen for growers to “be more streetwise” about how they use chemicals amid a climate of disappearing products and evolving pest profiles.

Weeds: changing challenges

Resistant blackgrass is the one single weed that continually dominates the farming press, with its control now costing growers up to £100/ha, in some cases rendering fields uncroppable for cereals.

This high cost is due to the greater challenge of controlling the weed with fewer actives available and increasing levels of resistance. Resistance is spreading and of the 20,000 farms known to use herbicides to control blackgrass, it now is estimated that 80% or more of those will have some level of resistance to at least one herbicide.

Atlantis (iodosulfuron + mesosulfuron) efficacy has been falling in recent years and there has been a switch in emphasis, with growers hitting blackgrass early with a combination of pre-emergence residual herbicides (stacking) followed up by a post-emergence later in the season.

However, Lynn Tatnell from ADAS believes this fixation on treating blackgrass may be leading farmers to be inadvertently building up resistance in broad-leaved weeds such as poppies.

“We started a project last year with the HGCA, BASF, DuPont and Dow AgroSciences to try to understand whether we’re forcing poppies to become more resistant because you can use an ALS-inhibitor herbicide now in every part of your rotation.

“You probably wouldn’t be using it to control poppies, but if you’re putting it on to control blackgrass, some of it may be affecting poppies to a lower level so you’re always putting the resistance risk there.”

ADAS is trialling how quickly the resistant shift to herbicides in poppies is.

“We don’t think it’s as fast as blackgrass, where we’re obviously in a bad state. We’re not suggesting that it will get that bad for broad-leaved weeds, but there is always that risk – it’s bad in Italy, Spain and France. If we include more spring cropping we might be encouraging more broad-leaved weeds, particularly if people don’t alternate the chemistry. We could be making the problem worse.”

Traditional treatments such as MCPA will continue to wipe poppy populations out, but Mrs Tatnell is concerned that if farmers lose actives such as pendimethalin, this will push more growers into using more ALS-inhibitor herbicides.

Alongside poppies, mayweed and chickweed are the two broad-leaved weeds that also pose an emerging threat. Reports of herbicide resistance in chickweed in the north of England and throughout Scotland are becoming more common.

Mark Ballingall, a senior weed consultant at Scotland’s Rural College, is thankful that problems with blackgrass are limited to some parts of East Lothian and the Borders, but says that brome is still the major weed in Scottish cereal and oilseed crops.

“Brome is becoming more of a field weed instead of a headland weed in parts of Scotland,” he said, adding that the change in profile is largely down to modern cultivation techniques.

Glyphosate remains a key herbicide and its continuing efficacy is seeing greater focus overseas with increasing reports of resistance.

Glyphosate

Paul Neve, an assistant professor at Warwick University, is working with PhD student Laura Davies to examine whether glyphosate resistance is likely to be seen in the UK. While he doesn’t expect her research to uncover any resistant populations, he says it would be a “major problem” for growers if it developed.

“As we lose other available herbicides glyphosate becomes more and more important,” he says.

“Globally there are now 24 weed species with confirmed glyphosate resistance. Most are in North America and associated with GM crops. There are also some cases in Europe, but they are entirely in perennial crops such as vines, citrus and olive crops.”

The project tested samples from 40 different blackgrass populations across affected areas of the UK. No resistance was found, and the weed was still being controlled by the field-recommended rate of glyphosate. Ms Davies did, however, find variation in sensitivity to glyphosate at lower than recommended doses, with less sensitive populations tending to be from fields with a history of more intense glyphosate use.