Tips to minimise potato storage spoilage losses

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Potato growers have entered some uncharted waters, as they cope with without using the desiccant diquat.

In addition, spuds are now being loaded into store, with no prospect of treatment using the cheap, but now-banned sprout suppressant CIPC (chlorpropham), adding further uncertainty to the production process.

See also: Why whole-field stewardship has a place in arable rotations

While these product losses grab the headlines and threaten to increase storage losses via some knock-on effects, some of the same old problems are also lurking to catch growers off-guard this season.

Two potato storage experts give tips on how to minimise losses as we enter the 2020-21 storage period.

Be vigilant against blackleg

Reports from agronomists suggest that levels of blackleg being seen in crops this year is relatively normal, but it is always something that growers should be very wary of in crops destined for storage.

Rain in early September has resulted in the wetting of soils, particularly in low spots, along sprayer tramlines and headlands, heightening the risk of bacterial infection spreading through the crop.

Another factor increasing the risk of bacterial spread is the switch to mechanical flailing to destroy haulm after the withdrawal of diquat, with estimates suggesting some 75% of farms are now using a topper.

Furthermore, achieving skin set is taking longer using diquat alternatives, so crops may be in the ground and exposed to infection longer. If tubers are harvested before skins are fully set, there is the potential for scuffing during the harvesting.

This opens up the possibility of secondary infection of tubers with a range of pathogens that can cause losses post harvest.

The slower desiccation process without diquat has increased the risk of blackleg © Blackthorn Arable

There are also reports of swollen lenticels in some crops after recent rains, and cracked skins caused by potato virus Y (strain NTN), both of which offer routes into the tuber for bacterial and other infections.

This means regular field inspections should be carried out ahead of harvesting crops destined for long-term storage to identify areas of concern.

Varietal susceptibility should also be factored into harvesting and storage plans, with processing varieties such as Markies, Agria and Royal all more prone to bacterial infection.

Norfolk-based storage specialist Tim Kitson of Potato Solutions says infection is present in crops where good, clean seed was planted, so assumptions should not be made about risk.

“It ties up with the work carried out at the James Hutton Institute, which suggests airborne transmission plays a role in the spread of bacterial infection. It’s certainly out there and could cause problems.

“Where there is infection in a crop, don’t store it – lose it. The first loss is the best loss and will avoid any disasters later on,” he explains.

Check for tuber blight

While blight pressure hasn’t been significant through much of the growing season, the back end has seen the return of damper, cooler weather, bringing with it the potential for tuber blight infection.

As with blackleg, a slower desiccation process without diquat and potential regrowth of green leaf area may increase risk of tuber blight infection as the maincrop harvest gathers pace.

Areas in wet wheelings may also be difficult to completely flail and/or burn off, so could be a source of inoculum that infects tubers and causes issues in store at a later date.

Adrian Cunnington, head of AHDB’s Sutton Bridge Crop Storage Research, says it is vital that growers maintain adequate blight programmes right up to lifting to reduce the risk of blight reaching stores.

Regular field inspections and sampling will identify infection foci, and a hotbox is a useful tool to accelerate development of any asymptomatic infection on sampled tubers.

Infected crops should not be stored and those identified as at risk should be stored separately and where easily accessible, so it can be swiftly removed if tubers begin to break down.

Tuber blight © Blackthorn Arable

“It is not always easy to see in the field, so it’s about having a good quality control process and gathering as much information as possible so you are not storing crops blind.

“There is plenty of information on diseases, defects and sampling assessment ahead of storage on the AHDB website,” he adds.

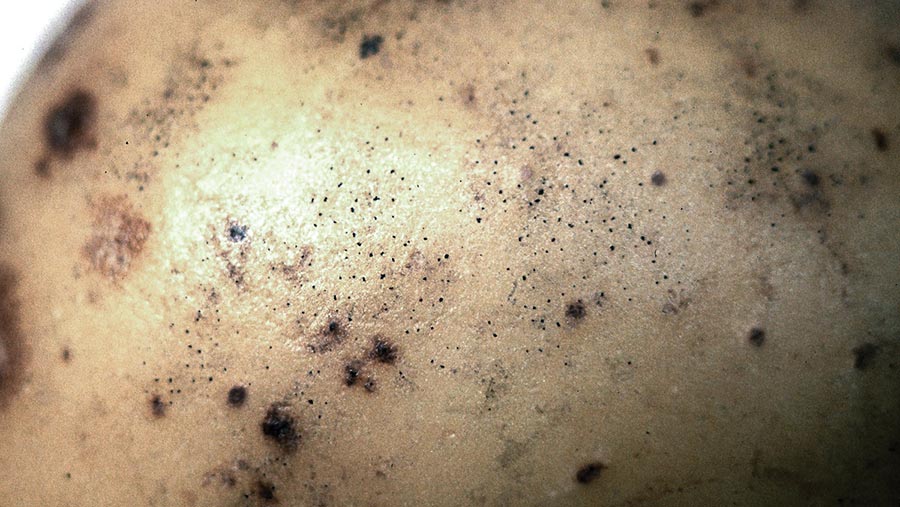

Beware black dot

Where crops are left in the ground for a longer period, either waiting for skin set or because of harvest delays, black dot could be a problem.

A thorn in the side of pre-pack potato growers, skin blemish black dot is caused by the seed- and soil-borne fungus Colletotrichum coccodes.

It gets its common name from its symptoms, which appear as tiny jet-black microsclerotia just visible to the naked eye on stems, stolons and roots late in the growing season. If the disease progresses, they also appear on tubers at harvest.

Given warm (above 9C) and humid conditions in store, faint shadow-like lesions progress into unsightly brown patches, or on red tubers, silver patches that can be confused with silver scurf.

Mr Cunnington says if black dot is picked up on tubers coming into store, temperatures should be reduced as quickly as possible to minimise disease progression and avoid quality loss.

Those geared up to grow for the fresh market will typically have refrigeration and will be able to reduce temperatures, but the practicalities of store loading will mean a delicate balancing act is required until the whole store can be pulled down.

Black dot can prove costly for growers, with tubers downgraded © Blackthorn Arable

“You can’t reduce the temperature too fast when you still have crop to come in, so it becomes a question of compromise, particularly where you get harvest delays.”

Where storekeepers would typically hold the store at 7-8C through the duration of loading before pulling the whole store down to about 3C, Mr Cunnington says it might be appropriate to drop that holding temperature by 1-2C if black dot is present.

“If you get it wrong, quality can drop from the highest supermarket grade to catering or peeling markets at significant cost to the grower.”

Don’t let sprout control costs spiral

The loss of chlorpropham (CIPC) has been a hot topic for the past 12 months and as growers head into their first harvest without it, they must pay close attention to crop condition coming into store.

Many will have applied maleic hydrazide (MH) – a foliar-applied systemic growth regulator that can give a period of early sprout control – for the first time this year.

This will give growers some breathing space early in the storage period and delay the need for treatment with other sprout control options ethylene and, in particular, mint oil, which costs much more than CIPC.

There has been much knowledge exchanged on correct use of MH in recent months, particularly relating to application conditions, but good uptake and distribution in the plant is not guaranteed.

Tim Kitson says some sprout growth has already been seen in MH-treated crops in the field and warns that growers should not be complacent as crops go into store.

“Where you missed the MH application window or where you see issues in treated crops, ensure that the potatoes are stored where they can be accessed easily for removal,” he explains.

Adrian Cunnington adds that planning and early store management will be key, stressing that stores should be filled as quickly as possible – particularly box stores taking in multiple lots – to allow for rapid drying, cooling and pulldown.

This will minimise sprouting risk and avoid having to treat a whole store with mint oil to burn back sprouts on just a few tonnes of early-harvested crop.

“Store management that sees multiple lots all over the place will be exposed by the position we are in with sprout suppressants.

“I would encourage growers to have a lot more dialogue with fogging contractors now, because mint oil is not the same blunt tool that CIPC was and will require a lot more thought to optimise application timing,” adds Mr Cunnington.

Gather intelligence on fry colour

Slow skin set potentially risks the harvesting of chemically immature tubers, which tend to have elevated levels of sucrose going into store and results in dark fry colour in chipping and crisping potatoes.

Each field should be rigorously sampled and tested for fry colour and where fry quality problems are identified, problem potatoes should be kept separate to avoid compromising marketability of good stocks.

Information from fry colour analysis can then be used to manage crop duration. The best crops should be earmarked for long-term storage and those with fry colour issues moved sooner rather than later, according to Mr Cunnington.

While there are means of addressing tuber immaturity and manipulating sugar levels in store, putting crops with variable fry colour into long-term storage can exacerbate problems in some varieties, particularly at lower temperatures.

“The underlying message is to gather as much intelligence as possible and also talk to your market. If the crop is scheduled to be delivered in six months’ time, could they take it a bit earlier?”

Don’t pull down ambient store temperatures too soon

Early September saw the arrival of cooler temperatures, but since dropping into single figures at night, they have been up into the mid-teens again and Mr Kitson says fluctuations like this can cause significant problems in ambient stores.

When putting a new crop into store, it is typically dried and cured to heal wounds at a temperature of 12C, before dropping down to about 8-9C.

Cool air will need to be blown through the crop periodically and where a store has a fridge, this can be done in any weather.

However, if you are relying on ambient cooling and night-time temperatures rise to 12-15C, where a store has already been pulled down, it results in warmer air being blown through a cold crop and this will cause condensation – the number-one enemy in potato stores.

If there is any disease in the crop – particularly bacterial soft rots or tuber blight – this can quickly accelerate development or spread, resulting in rapid breakdown of tubers and significant losses.

“You have to consider the cooling capability of your store before pulling down and ensure the crop is stable enough in terms of dormancy, so it can handle any warmer spells.

“Also keep an eye on the weather and try to wait for stable night-time temperatures, or you could get yourself in a muddle,” says Mr Kitson.

Avoid excessive weight loss

For a six-month storage period, storekeepers should be aiming for a weight loss of 4-7%. Any figure above this range is a likely indication that a store is not operating or being managed as it should.

To avoid excessive weight loss, growers should focus drying, curing and pulling the crop down to holding temperature as quickly as possible to prevent issues that will require additional ventilation.

“It is easy to get preoccupied with harvest itself and not focus enough attention on what is happening in store, but this should be managed from day one,” says Mr Cunnington.

Higher weight loss figures can also be a symptom of poor or uneven airflow, which leads to uneven temperatures in the crop. The result is over-ventilation in an attempt to compensate, dehydrating the crop and causing weight loss in the process.

Efforts should be made to improve airflow and where humidifiers are available, switching them on will avoid use of dry air for cooling and venting. Humid air also helps to speed up wound healing, ultimately reducing weight loss.

“Where you have a crop in good condition, think about how much air it needs blowing through it. You should aim to use just enough to hold it, but not enough to dehydrate,” explains Mr Kitson.

Although it is likely to be too late for this season, Mr Cunnington says refrigeration equipment can also be a factor in increased weight loss, with poorly functioning units resulting in excessive ventilation to bring crops down to temperature.

These should be regularly serviced and recharged to ensure they are working to their maximum capability ahead of each storage period.

Other considerations

- Bruising Assess crops and harvest and handling processes for bruising risk. Try to minimise bruising at all costs, as defect tolerances among customers are likely to be tight this year.

- Growth cracking As many tubers with defects such as growth cracks should be removed before a crop is stored. Holding on to unmarketable product will unnecessarily add to storage costs, which are already on the rise.

- Blackheart Another issue for fresh growers is blackheart, a defect that develops if a crop is depleted of oxygen. Tubers usually appear healthy on the outside, but a dark brown or black necrotic cavity forms inside. Risk factors include low storage temperatures and condensation, which should be avoided. Where using ethylene, it must be introduced very slowly (ramped), as rapid introduction can increase blackheart risk. Varietal susceptibility is also a factor. Sutton Bridge Crop Storage Research has developed methodologies to evaluate blackheart susceptibility and where issues are identified, the crop should be marketed ahead of any other stock.