Are growers paying too much for sugar beet weed control?

Trials this year show that some sugar beet growers might be spending too much on herbicides, with some commonly used and effective broad-leaved weed control programmes showing a huge range in cost.

The 2021 sugar beet crop is the first that hasn’t been widely treated with herbicide desmedipham after the weed killer’s withdrawal last summer.

Its loss has seen growers and agronomists reassessing weed control strategies this year and forced them to mix and match straight products – something that many will not have done for several years.

See also: How to establish in-field flowering strips to manage pests

In doing so, UPL’s national influencer and sugar beet weed control expert Pam Chambers believes some farms have taken an unnecessarily heavy-handed approach and this has been demonstrated by the company’s extensive trials this season.

Pam Chamers © MAG/Adam Clarke

Programme comparison

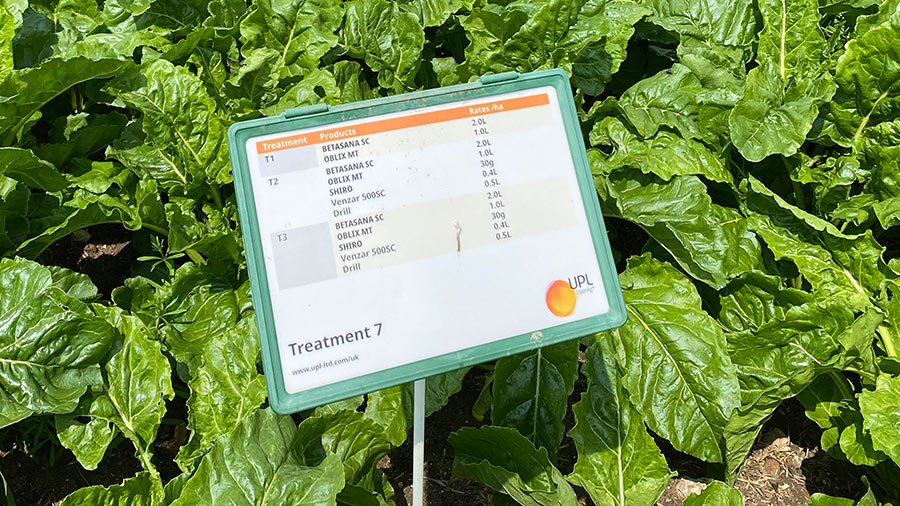

The experiments compared several programmed approaches to broad-leaved weed control using post-emergence sprays only.

Farmers Weekly visited one UPL site near Diss in south Norfolk, where Ms Chambers says all treatments provided commercially acceptable levels of weed control, with no significant differences in final weed counts after all sprays had been applied.

View of the Diss trial fields © Blackthorn Arable Ltd

However, taking average prices from independent sources, costs ranged from £100 for a two-spray programme, up to £180 for a three-spray approach for similar results.

It should be noted that costs could be considerably higher if problem weeds such as thistle, volunteer potatoes and grassweeds such as blackgrass were present

The most cost-effective option on the site – where many weed species commonly found in sugar beet were present (see below) – was a two-spray programme based on the “broadacre approach”.

The total herbicide applied across two sprays was 800g/ha of phenmedipham, 700g/ha of metamitron, 400g/ha of ethofumesate and 20g/ha of triflusulfuron-methyl, along with 0.5litres/ha of adjuvant oil.

The first dose was applied when the crop reached one true leaf and 1cm of growth stage and the second a week later.

This approach can check the crop, but Ms Chambers says this rarely translates into a yield penalty at the end of the season.

“The inclusion of triflusulfuron-methyl is useful because this approach usually starts later than other programmes, so weeds tend to be bigger.

In this field it worked well, and cost came out at about £96/ha,” she explains.

Conventional approach

Slightly more expensive at £116/ha was a three-spray approach using three actives – phenmedipham, ethofumesate and metamitron – applied when weeds are small, otherwise known as the conventional approach.

This relies on good conditions at spraying, like those experienced this season where sprayers were able to get herbicide applied in the relatively settled month of April across the British sugar beet area. Growers also need the capacity to get around their beet area at the correct time.

As the trial was pre-planned, the protocol was followed closely and applied 960g/ha of phenmedipham, 450g/ha ethofumesate and 2,100g/ha of metamitron, partnered with 0.5litres/ha of oil.

However, Ms Chambers says in a commercial situation further savings could have been made by reducing rates if conditions allowed, potentially trimming costs even further to under £100/ha.

At the other end of the spectrum, one programme used the same actives and rates as the conventional approach, but in three sprays and with the addition of 400g/ha of lenacil and 30g/ha triflusulfuron-methyl.

This pushed spend up to a hefty £170/ha without the extra actives providing any improvement to weed control on this site.

There is anecdotal evidence to suggest some farms are using this belt and braces approach, but the results show it is not always necessary.

“Applying big expensive hits of herbicide all at once hoping it will cover all bases does not guarantee good control, despite the high cost.

“Actives and rates must be matched to the weed spectrum present and in some cases allows growers to reduce inputs,” says Ms Chambers.

© MAG/Adam Clarke

Benchmarking

British Sugar’s head of central agriculture Nick Morris recognises that there is a large spread of herbicide costs among growers, and this can be due to uncontrollable factors such as soil type.

However, he says that like any other crop production cost, sugar beet herbicides should be carefully scrutinised to maximise net margin and is a practice that can be improved on some farms.

He adds that without desmedipham – which was a relatively expensive active – and the move back to straight generic products, there is now a good opportunity to economise on herbicides.

He suggests three areas to focus on, including: whether product use, applications and dose can be reduced; whether products can be purchased more competitively; and finally, whether farms are getting the most out of what they buy when it is applied.

On the first point, product use, applications and dose are very site specific, and some will be pushed into a costly programme by the addition of expensive actives to control problem weeds.

Similarly, a farm system may need flexibility on application timing if sprayer capacity is at full stretch and opt for a more robust approach in terms of actives and dose.

However, all growers can look at the second and third points as areas where savings or improvements can be made.

“There are sometimes massive differences between supplier A and supplier B in terms of product price, but farmers tend to be loyal to where they buy from.

“But as with any business, it’s important to benchmark suppliers and ensure that you are getting your herbicides at a competitive price,” he notes.

Application

On the third point, Arable Alliance independent agronomist Andrew Wells, who walks sugar beet crops across Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire, says application and timing can make a massive difference to the value extracted from herbicide programmes.

He says that the same recommendation can be made on two separate farms, but a 10-15% variation can be seen in weed control purely through timing and application technique.

Ensuring these are better may allow for reduction of herbicide input.

“Operator input can make a massive difference. It’s important to keep the boom low, so forward speed needs to be slow and boom stability good enough to achieve that.

“A nozzle that produces a fine droplet is also important, particularly as we are targeting small weeds,” he explains.

Mr Wells has never relied on desmedipham for his broad-leaved weed control, instead using the conventional approach where he typically recommends three-sprays containing varying rates of phenmedipham, ethofumesate and metamitron.

This season, this approach cost him about £105/ha including adjuvant oil, having budgeted £110-£120/ha, and he says the focus in cost saving comes from adjusting metamitron rates, being more costly than the other two.

However, where knotgrass and fat hen are present, at least 1.750g/ha of metamitron needs to be used to get adequate control and this inevitably pushes spend higher.

Similarly, increasing incidence of umbelliferous weeds such as fools’ parsley and bur chervil is pushing some growers into adding triflusulfuron-methyl or low rates of clopyralid into the mix.

Mr Wells acknowledges there are weedy situations where you will end up in a mess if you don’t spend the money and growers accept that, but on many sites, it is possible to keep herbicide spend sensible with careful management.

“It really is about balancing the site’s weed species and conditions at application to the right actives at the right rates.

“That does mean walking fields and treating every seven to 10 days when weeds are small. If you have to firefight, it will push you into a high-cost programme,” he adds.

Weed screen reminds growers of strengths and weaknesses of individual actives

Alongside the programmes, each year UPLs trials include a weed screen that tests individual sugar beet actives or active combinations in a three-spray scenario to help demonstrate their strengths and weaknesses.

At one of its sites near Diss in Norfolk, there was a relatively high weed burden (see graph, above) on a sandy clay loam soil prepared for drilling using minimum tillage.

Ms Chambers says that it was possible to see variation between actives by the second spray, with the uncontrolled weeds growing through the treatments.

Key findings are summarised in the table below.

Summary of key UPL weed screen findings |

||

|

Active(s) |

Example products |

Key observations |

|

Phenmedipham (Contact; post-emergence) |

|

|

|

Ethofumesate (Contact and residual; pre- and post-emergence) |

|

|

|

Metamitron (Contact and residual; pre- and post-emergence) |

|

|

|

Lenacil (Residual; post-emergence) |

|

|

|

Dimethenamid-P + quinmerac (Contact and residual; post-emergence) |

|

|

|

Clomazone* |

|

|

|

Triflusulfuron-methyl (Mainly contact; post-emergence) |

|

|

Independent weed scientist Gillian Champion says the value of weed screens for sugar beet growers has increased post-desmedipham and big co-formulated products, with growers now largely reliant on mixing products with one or two active ingredients.

However, there is little value in knowing strengths and weaknesses of individual actives without being able to identify weeds to ensure they are used appropriately.

She says there is no replacement for experience when it comes to weed ID, so any young agronomists or growers are advised to find a mentor with an extensive knowledge of weeds to learn how to identify key species.

Most plant ID books focus on the flowers and seeds in illustrations, but as weeds are best and more cost effectively controlled when at the cotyledon stage in sugar beet, it is key to identify them when small.

Dr Champion recommends The Identification of Weed Seedlings of Farm and Garden by RJ Chancellor, which remains the best guide at the earliest stages of weed growth, despite its 1966 publication date. It is no longer in print, but copies are available on line.

“There are some apps available which I’ve tried, and they have lots of potential to develop into very useful tools in the future, but they do rely on being fed accurate information on [submitted] pictures to learn correctly, and aren’t quite there yet,” she adds.

Common mistakes

One weed ID mistake is telling the difference between fat hen and orache, which are both members of the Chenopodium family.

Orache is regarded as the tougher one to control and while phenmedipham does kill both species, UPL’s weed screen data from the past four years shows it can vary in performance on orache depending on conditions.

Ms Chambers says in practice growers would never rely on phenmedipham alone for orache control, but reinforces why it’s important to know actives and weeds, and regular walking will allow them to react to any weaknesses – in this case phenmedipham activity on orache in cool conditions – in the next herbicide application.

Dr Champion says the key differences are in colour and shape, with fat hen having a reddish tint to the underside of cotyledons, which narrow to a fine stalk at the base.

Conversely, orache is green and is “chunkier” at the base of the cotyledon (see photos).

Orache weed © Blackthorn Arable Ltd

Another in the Chenopodium family is fig leaf goosefoot, which looks the same as fat hen at the cotyledon stage but when true leaves appear, they have two distinct lobes at the base of each leaf, which are then wavy to the tip.

Fat Hen weed © Blackthorn Arable Ltd

Fig leaf goosefoot weed © Gillian Champion

Bindweed

At the Diss site, there was also some confusion between field bindweed and black bindweed. At the cotyledon stage they are quite easy to tell apart, with field bindweed being kidney shaped and black bindweed long and narrow.

True leaves are more similar, but black bindweed has rounded lobes at the base of the leaf and a much sharper point at the tip, whereas field bindweed has pointed lobes at the base but more rounded at the tip.

Field bindweed is almost impossible to control in crop, as it generally grows from root fragments in the soil. Black bindweed is well controlled in beet crops by actives such as ethofumesate, phenmedipham, clopyralid and lenacil.