Biomass boiler proves crucial in planning process

Biomass boilers offer the opportunity to create extra income and can make an attractive proposition to planners, as Nick Fone found out on a visit to a farm-based community heating scheme in Somerset.

Talk of on-farm energy production often conjures up visions of complicated anaerobic digesters and towering wind turbines. But producing energy on-farm needn’t necessarily be a complex or costly process.

Providing heat for homes can provide a good income and doesn’t have to clash with core farming activities. Moreover, it fits with government objectives for renewable energy strategies and can consequently find favour with planners.

For Somerset arable and dairy farmer Archie Montgomery, on-farm energy production has long been an objective in his business plans. Ten years ago he started growing miscanthus to supply planned biomass power stations through the now-defunct Bical.

“For a long time it’s been obvious that the continual rises in energy prices just aren’t going to stop,” he explains.

With a good acreage of farm woodland, a cheese production plant, potato grading and washing line and two dairy herds, the Montgomeries had a few options to look at.

“We’ve considered anaerobic digesters, wind turbines and solar panels and haven’t written any of them off yet. But using the biomass we were already growing on-site made sense for our first project, especially when Bical started to falter and it looked like we might not have a market for our miscanthus.”

As things began to look rocky on that front, the farm had another dilemma to face. Redundant stone-built sheds and barns were beginning to show their age and needed some fairly serious work. But, as is often the case, the expense of renovating buildings with no use in modern agriculture was difficult to justify.

Development into residential dwellings proved the only realistic opportunity. But of course this wasn’t straightforward – the planners needed to be satisfied. “The planning process was tricky but that’s when I realised our biomass idea would fit in.”

With council planning departments now expected to look favourably on projects with a renewable energy inclusion, many are struggling to meet government targets for sustainability.

“I offered to help Somerset District Council by heating all 27 houses on the development centrally with a boiler burning material produced on the farm or from wood waste. They jumped at the chance, which I’m sure helped my planning application.”

Sourcing the technology became the next issue. An energy use calculation was done and a 185kW unit was ordered from German firm Binder. UK agent Wood Energy helped in sourcing a 40% capital grant for the boiler’s installation.

Good as this was, it soon became apparent that it only stretched as far as boiler installation and did not cover the 400m of highly expensive, insulated piping required or the heat exchangers and metering units in each property.

The boiler and its 8000-litre buffer tank were installed in a building next to a redundant grain dryer which now acts as a storage hopper for the feedstock. By siting it close to the development, pipework and the associated heat losses (and expense) have been kept to a minimum.

Initially a mix of chipped wood and miscanthus with a moisture content of 15-20% was used to fire the boiler but its diet has been tweaked since its installation.

“Tarry substances in the miscanthus separate out during the burn to form clinker which means it’s not running efficiently and needs cleaning out regularly,” explains Mr Montgomery.

“In addition, cereal straw it can have a high chlorine content, which turns to hydrochloric acid and damages the heat exchangers.

“We’ve since found a higher-value market for the miscanthus as horse bedding and have found other sources of wood.”

In the main, untreated and unpainted timber such as pallets and potato boxes is used. Fallen trees and thinnings from the woodland make up a small percentage of the feedstock but these require a big, powerful chipper.

A machine is hired in as required. The aim is to produce more fuel from home-grown wood to provide a better guarantee of quality fuel. But this requires an even supply year-round and covered storage.

“Ideally we’d set up a co-operative to source virgin timber and share a big chipper around several similar schemes.”

As well as the feedstock issue and its effect on boiler efficiency, other concerns have become apparent since the project’s inception.

“The plant has a high parasitic electrical requirement and that’s something we’re trying to address with Binder,” says Mr Montgomery.

“To get farmers’ confidence, it is critical that the government’s planned renewable heat incentive applies to the few projects up and running. Otherwise it’s the early adopters that have all the issues – such as these – and none of the rewards.”

Total cost for the project, now in its second year of operation, has reached almost £100,000.

“The expense is vast and initially we’d looked to get payback in 15 years. But we’ve had to put half the development on hold since the market’s dropped and that’s pushed the payback to 25 years.”

With that timescale, the return on investment doesn’t look too rosy and, in truth, the project only makes financial sense with 27 homes included in the scheme. But, without the biomass scheme, Mr Montgomery believes planning would have been a great deal harder in the first place.

“If we can just communicate with developers and planners, we can help them to meet their sustainability criteria with community heat – and power – schemes and generate a decent alternative income for the farm.”

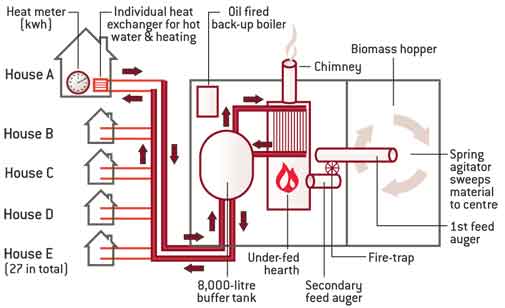

HOW IT WORKS

As chip is fed from the hopper into the burn chamber, airflow is adjusted to control the amount of heat produced according to the system load at that time.

Hot water is buffer stored in a tank and then piped to houses on the site. Most have underfloor heating and a separate heat exchanger for hot water.

Through winter the system runs flat out while in summer it ticks over at a lower level, providing just hot water. Any excess is pumped off to a swimming pool which acts as a convenient heat sink.

A meter in each house records energy usage and relays this by radio link to the office computer. Measured in kilowatts, heat usage is then converted to an equivalent figure for a oil-fired boiler to give a final value. Residents then receive a quarterly bill with a 10% discount for loyalty to the scheme.