Why ramularia is so difficult to control in barley

© Malcolm Case-Green/Alamy Stock Photo

© Malcolm Case-Green/Alamy Stock Photo For a relatively new disease, ramularia leaf spot has been making its presence felt in both winter and spring barley crops across the UK, with yield losses as high as 0.5t/ha.

The fungus, Ramularia collo-cygni, has a complex relationship with the host plant, so symptoms – when they finally show late in the season – are often mistaken for other less-damaging diseases.

Added to that, in the past two years the endophytic fungus has developed the ability to overcome the activity of three of the main fungicide groups – leaving the endangered chlorothalonil (CTL) as the only effective fungicide for control.

In short, ramularia is hard to predict, tricky to identify and difficult to control. The cost of the disease to the barley industry has been estimated at £10m/year.

See also: Analysis: What a ban on fungicide chlorothalonil would mean

As Neil Havis of Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) explains, not only does ramularia have the ability to go undetected for much of the growing season, since 2017 the pathogen has been resistant to SDHIs and triazoles, as well as strobilurins, so is untroubled by much of the chemical armoury available to barley growers.

“That latest resistance developments happened quickly and without much warning, which suggests that it’s a very diverse population with a lot of genetic variation.

“In the UK, we now see no activity from these fungicides. But it’s a mixed picture in other countries, with some of these chemistries still working or giving partial control.”

How to identify ramularia

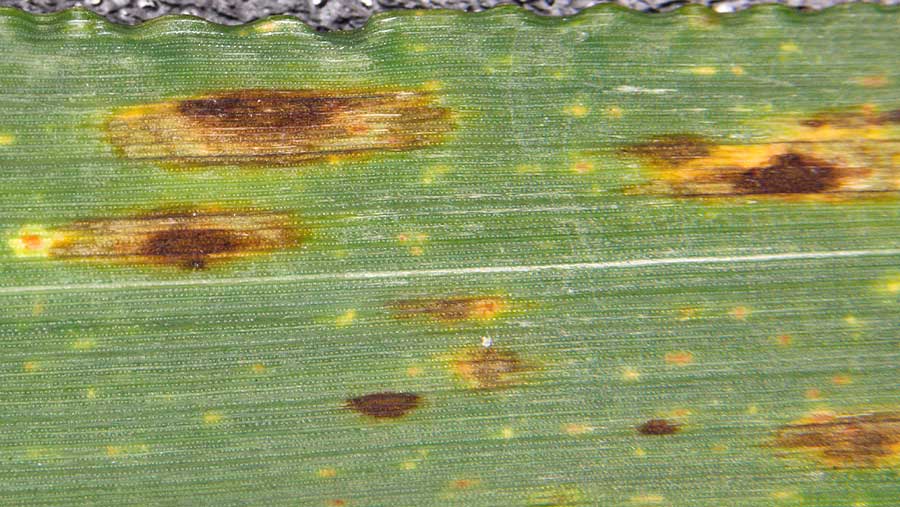

Symptoms appear on the upper leaves after flowering. Initially they resemble a fine spot, which then darken to a square spot, bounded by leaf veins and surrounded by a chlorotic halo.

To help with identification, the AHDB and SRUC have devised a guide based on the 5Rs:-

- Ringed with yellow margin of chlorosis

- Rectangular shape

- Restricted by leaf veins

- Reddish-brown colouration

- Right through the leaf

There is also an AHDB video, featuring Dr Havis, which helps with ramularia identification and scoring.

Other diseases, which ramularia is often mistaken for, include the spot form of net blotch and tan spot, as well as physiological spotting.

To clarify, net blotch and tan spot lesions are neither rectangular nor restricted by leaf veins, while physiological spots leave the undersides of leaves unaffected.

Ramularia infection on barley leaf © Blackthorn Arable

The pathogen

SRUC work has shown that the pathogen responsible for ramularia leaf spot has a genetic make-up that disguises it, so it isn’t initially detected by the host plant’s defence mechanism.

“That allows it to remain benign in the plant until there’s a change in the host, perhaps as a result of environmental stress factors, which triggers the production of toxins,” says Dr Havis.

“These cause the characteristic brown spots to appear on the crop leaves.”

This unusual characteristic makes it a difficult disease to forecast, as it goes unnoticed for much of the growing season. It tends to show in crops from growth stage 72 onwards, after flowering.

Attempts to identify the environmental variables that influence disease epidemics are ongoing; initial work looking at leaf wetness after stem extension suggested that a risk model based on a single factor wasn’t accurate enough across seasons.

“Given the nature of the fungus, factors which affect the growth of the fungus and the growth of the crop are relevant to the severity of the disease. A more accurate forecast will need to take account of a number of environmental variables.”

Life cycle

The fungus that causes ramularia grows from infected seed, with most seed stocks now carrying it under the seed coat.

Seed treatments are ineffective – those that are applied as surface dressings don’t get to the pathogen, which is carried deep in the seed. SDHI treatments, which used to have an effect, have now been lost to resistance.

Once the seed has germinated, the ramularia fungus then moves systemically within new plant growth. Visible symptoms are not apparent at this stage, with the fungus seeming to cause no harm.

A secondary spore type has been observed on trash and crop debris and late in the season these structures produce airborne spores that can also infect plants, volunteers and potentially early autumn-sown crops.

Symptoms only appear after the crop has been under stress. This may be as a result of drought, waterlogging or heat, for example, although flowering is considered to be the main stress that initiates changes in how the fungus and host interact.

“That’s what happens with some endophytes – as the plant starts to senesce, they start to produce toxins which break down the hosts tissues.”

Subsequently, infection spreads to the ears, which is how the seed becomes infected and the problem persists.

“An obvious action is for farmers to avoid saving seed from heavily infected crops,” advises Dr Havis.

Varietal resistance

That latest version of the AHDB Recommended List does not include ramularia disease ratings for barley varieties.

Following the discovery that a single assessment taken late in the season is not an appropriate measurement across seasons, the ratings have been suspended. There are now plans for multiple assessments to be taken by a single assessor, across a range of varieties.

“That will happen across three trials in 2019 and again in 2020, in areas where high levels of ramularia are the norm,” says Dr Havis. “There was too much variation across 26 sites to give meaningful scores.”

He adds that the intention is to bring varietal ratings back, so that growers have all the information they need.

He also points out that new varietal resistance is needed. “Plant breeders should make it a priority. The fungus is causing problems across Europe, as well as in other parts of the world.”

Ramularia control

- Take note of weather – warm and wet conditions favour the fungus

- Include CTL in the T2 timing at up to 1litre/ha; at T1 it will do no harm

- No stand-out varieties for resistance

- Symptoms appear after flowering, from growth stage 72 onwards

- Use the 5Rs for identification

- Avoid farm-saving seed from heavily infected crops

Chlorothalonil is not affected by mutations in the ramularia fungus and should be included in programmes to ensure control.

While most growers will have it in the T1 spray as part of their anti-resistance strategy, its use at T2 at 1 litre/ha is the important timing for ramularia.

“In general, the later you put it on, the better the ramularia control,” says Dr Havis. “Our advice is to go for GS45-49 – you can go later, but it’s a risk if the weather changes.”

Be aware of the weather conditions when deciding about treatment, he suggests. “If it’s warm and wet, it will favour the fungus. There wasn’t much ramularia in 2018, because it was very dry.”

Another multi-site, folpet, has not given control of ramularia in UK trials, he reports, but there has been activity recorded in New Zealand, so it will be looked at again this summer.

Dr Havis has also investigated the use of bio-elicitors, having seen a consistent effect against all diseases when they are used.

“They fit into an integrated management strategy and allow you to cut back on fungicides. For ramularia control, we still recommend the use of CTL after an elicitor.”

They should be applied early, so that they switch on the plant’s natural defence mechanism and prime the plant before the chemistry is applied.

“With these, and with other biological products, they should be considered as building blocks for control. They can be used in programmes to add to each other, rather than relying on one product for 90% control.”