No-till case gains power

The use of fertilisers, pesticides, intensive tillage systems and more sophisticated technology has meant farmers are achieving higher yields than ever before.But is there another way? We look at the cases for and against conservation agriculture

There are few more contentious debates on the lips of farmers than whether to stick to conventional tillage methods, adopt min-till or to go all out and establish crops with a one-pass system. As fuel prices rocket, farm machinery costs grow and bottom lines get squeezed, a growing proportion are looking to the latter to remain sustainable. Added to this is the notion of establishing crops at a fraction of the cost while potentially increasing yields – something of a Holy Grail.

In some cases, it can all get quite heated. One reason is that farmers have been told repeatedly over the years to create perfect seed-beds, often by carrying out repeated passes with expensive pieces of kit, using lots of diesel and labour.

And some machinery manufacturers haven’t smoothed the way, either. After all, reduced tillage means fewer passes, and fewer passes mean the requirement for machinery is, well, less.

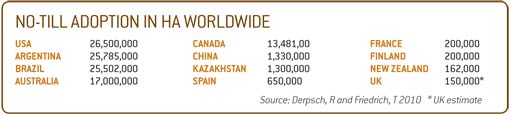

Thirty years ago, no-till was used to establish crops on about 2.8m ha of land globally. In 2010 this figure reached 117m ha, a 420% growth, according to international no-till specialist Rolf Derpsch.

The widely accepted benefit from reduced tillage in many countries is a higher profit per hectare due to increased productivity of both labour and machinery. And the environmental benefits are enough to please even the most fervent of conservationists, with reduced phosphorus and nitrogen losses as well as reduced greenhouse gas emissions to mention but a few.

By leaving the ground in a stable state with more organic matter, soil quality improves and erosion is minimised, explains Dr Derpsch. “Many South American governments support the concept of no-till by rewarding farmers that use the system with financial benefits like tax breaks.”

Traditionally, it’s been the belief that soil tillage is essential to establish crops. This often involves burying plant residues, establishing a stale seed-bed by leaving soil exposed and then spraying or using another pass to create an ideal seed-bed for seed to be planted. But, over the years, inherent problems have arisen. “Erosion is one of these problems and coupled with fertiliser run-off, degraded organic status and increasing oil prices, the case for conservation agriculture is becoming more obvious,” says Dr Derpsch.

For Will Scale, founding member of the No-Till Alliance and Nuffield Scholar on the subject of no-till and cover crops, the benefits of adopting conservation tillage are ecological, financial and social.

“Because you leave the stubble intact, you’re maintaining the soil structure and preserving the biological status quo. You’re also not disturbing the stubble and encouraging organic matter to create a more fertile growing environment.”

No-till adoption around the world

(Click on the numbers on the map for articles on direct drilling in Europe, Argentina and Australia)