Winter food sources help attract farmland birds

Providing food for birds during winter by sowing areas of wild bird seed mixes is an effective way of increasing numbers of key farmland birds, according to a study in Cambridgeshire.

Surveys have been carried out six times a year by an independent ornithologist, Alan Harris, at two Bayer CropScience development farms in Cambridgeshire for the past 10 years, explains Paul Goddard, the firm’s application and stewardship manager.

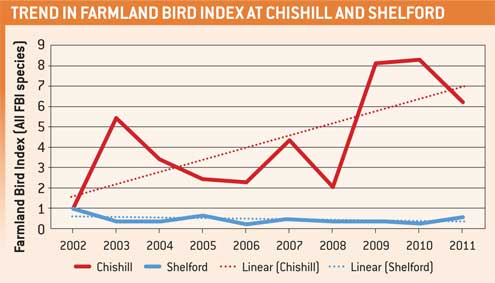

While the trend at the other development farm in Little Shelford mirrors the downward national trend for key farmland birds, analysis of the data by the RSPB’s Tony Morris suggests an upward trend in overall numbers of the 19 farmland bird species on the farm in the winter. In particular, the surveys suggest numbers of linnets, yellowhammers and finches have increased.

Numbers of these key species in the summer, which the government uses as an indicator of the health of the countryside, have remained stable on the farm during the 10-year period.

The farm fulfils an important business role as a testing ground for new and existing crop protection products, but Bayer, like many farmers, put in place environmental measures designed to increase bird, butterfly, insect and plant diversity on the farm, says Mr Goddard.

These include about 5km of field margins, two farm ponds and areas of woodland and orchard, as well as maintaining ancient hedges on the 20ha farm.

But the key measure that has helped increase the numbers of birds on the farm during the winter period has been the introduction of sources of winter food, believes Richard Winspear, senior agricultural adviser with the RSPB.

“All the species that have increased on the farm feed on seeds throughout the winter period. By introducing areas of plants that provide birds with those seeds you can usually see a response in the first year, which just grows and grows over the years.

“For example, at the RSPB’s Hope Farm, numbers of birds have increased eight-fold since we introduced areas of winter food.”

At Chishill, wild bird food seed mixes were first introduced about seven years ago, says farm manager Andy Blant. “Typically we plant two areas on the farm totalling about 0.4ha. We started off with areas of one-year and two-year mixes, but by the second year we were finding after the initial year of the mix there wasn’t much left, so we have tended to plant the one-year mix since.”

The mixes are planted in spring on field margins and contain quinoa, fodder radish, millet, oats, linseed and mustard. That’s important, as it means it produces both grain and oilseeds for birds to feed on, and some species prefer one or the other, says Mr Winspear.

“Yellowhammers feed on cereals grains, while linnets and finches feed on anything other than cereals, such as brassica seeds.”

Successfully feeding birds through the winter period can in some cases translate into increasing breeding pairs during the spring and summer, he points out. “That’s not always the case, as breeding pair numbers can be constrained by habitat availability. On a small site, such as at Chishill, breeding pair numbers could be at capacity, which is why numbers haven’t increased during the summer months.”

But feeding those birds during the winter is not a wasted effort, he stresses. “It will still mean better survival for the area as a whole, and those birds will find nesting habitat in the wider landscape.”

The environmental features at Chishill do provide a good natural habitat for linnets, finches and yellowhammers. Linnets prefer thick, thorny hedgerows or areas of brambles for nesting. “Chishill has both,” says Mr Goddard. “It has ancient hedgerows that are carefully managed, and remaining areas of orchards that provide an excellent overgrown habitat with areas of very dense brambles.”

Newer hedgerows have also been planted, replacing poplar windbreaks established when the farm was 100% orchard. “These are starting to mature and will provide more nesting areas in the future.”

Yellowhammers like to nest in the base of thick hedgerows, preferably where there is a wide margin or ditch. “All of the hedgerows at Chishill have 6m margins to the cropped arable land,” says Mr Goddard.

The importance of the winter food source is highlighted by the contrast in fortunes at Bayer’s other site at Little Shelford, where winter bird food mixes were only established for the second year this spring.

Bird numbers in the 10-year survey had been declining on the site, in line with the national trend, but following the introduction of winter food last year there was an immediate increase in the farmland bird index to its highest level since 2005. That backs up Mr Winspear’s observation that establishing winter bird seed mixes can provide an immediate response, although further survey data is required to confirm it is a real trend, Mr Goddard says.