Wet litter – it’s all about management

Management is crucial when it comes to minimising wet litter problems, as Philip Clarke reports.

There are three key factors at play when it comes to avoiding wet litter, and all of them are affected by the broiler keeper’s management skills.

The first, according to Stef de Smet of animal health company Kemin, is the choice and amount of litter material used, which affects water absorption capacity.

Most types of litter, from crushed straw to wood shavings, can be effective at absorbing moisture, he says.

“It is really about availability. You have to work with what you can get and the price you can afford. You may not always have access to the litter material you want, but I see people managing perfectly well with whatever they are using, so long as their management is good.”

The water:feed ratio

The second, and probably the key factor in determining litter quality, is moisture input – how much water is leaving the birds and ending up on the floor.

Feed plays a crucial role in this, in particular the salt and potassium content. “Automatically the salt which remains in the intestine will retain the moisture inside the gut, and that water will be excreted. You will see immediately that your water/feed ratio will increase.”

This ratio is a particularly useful tool to compare different flocks and feeds, and even to predict if something is going wrong, says Dr de Smet.

Similarly, differences in the fat content of the feed play a part. Trials in Belgium have shown that the more saturated the fat, the higher the water intake and the more wet litter is produced. This in turn leads to more foot pad lesions, breast blisters and hock burn.

The digestibility of the feed is also important for secretion levels. Products with lower digestibility will bind to water in the gut and again lead to wet litter. Undigested nutrients can also encourage certain bacteria, affecting intestinal health and causing diarrhoea.

On the subject of intestinal health, Dr de Smet identifies coccidiosis as a major cause of wet litter through its effect of inflaming the gut lining.

“Coccidiosis can be managed by coccidiostats, coupled with good shuttle programmes and good sanitation programmes on the farm. Vaccination can also be a solution if you have a coccidiosis problem.”

Dr de Smet also warns of the interaction between coccidiosis and dysbiosis, as once the intestinal wall is damaged, other bacteria can take advantage, creating a vicious circle.

“Dysbiosis is an imbalance in the intestinal microflora, which automatically leads to bacterial enteritis – you will always see inflammation,” he says. This will result in more mucus, more moisture in the gut and diarrhoea.

In the past this has always been managed effectively by using antibiotics. But the risk of antimicrobial resistance means producers and vets should be looking at alternatives, he advises, including probiotics, etheric oils, organic acids and medium chain fatty acids.

“All these solutions can be good, but management is equally important in avoiding wet litter.”

This includes drinking line management, adds Dr de Smet. Trials conducted in Belgium have revealed a clear correlation between high water pressure and wet litter.

“You have to find your own optimal levels for your farm, but it is clear that too high drinking line pressure causes wet litter.”

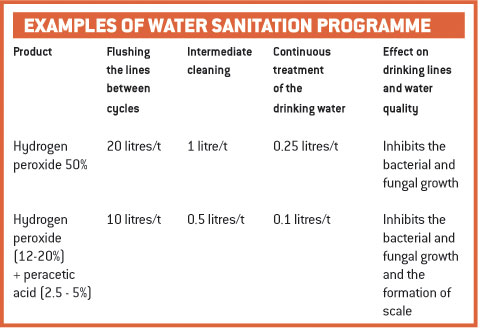

It is also important to avoid blockages by maintaining high sanitation in the drinking lines, with the use of hydrogen peroxide to inhibit bacterial and fungal growth, and peracetic acid, to prevent the formation of scale in hard waters (see table, below). “Scale is the first thing needed for the growing of biofilm.”

Climate control

The third factor in determining litter quality is moisture output – how much water is leaving the building in the air – and that is down to climate control.

“The only way to get water out is by evaporation,” says Dr de Smet. “What is important is, of course, the relative humidity and the temperature difference between the outside air and the inside air.

“At 10C the air can maximally contain 9g of water per cu m of air. At 20C it can contain 17g of water. If you heat that air another 10C, then it can take on another 14g of water, to total 31g. That is the way heating and ventilation helps you to get the water outside the house.”

Dr de Smet also points to the importance of insulation, so producers can heat inside the house more easily, and of avoiding cold floors to minimise condensation.

“I was recently on a farm in Hungary and the floor was very cold. It was impossible to avoid condensation. Cold surfaces are always a problem for litter conditions.”

As for the type of heating, Dr de Smet is adamant that indirect is far better than direct.

“Direct heating produces water, which is not good, though the worst thing is the CO2 production. This can easily exceed the 3,000ppm limit in the air and can cause ascites in the birds.”

But producers have to be realistic. “In Belgium, I know that 70% of the farms have direct heating and the people have to work with it. We don’t all have the money to invest in central heating. You have to be aware of the positive and negative sides of any system and manage it correctly.

“Some people have a direct heating system, but because of the price of the fuel, they don’t ventilate – that’s just asking for problems. You have to ventilate and how you manage the air flow can be even more important than how you manage the air volume.”

Three determinants of wet litter

- Litter material

- Moisture input levels

- Moisture output levels