Four clever inventions from a Hampshire farmer

If you can’t find the tool for the job, then why not make it? Oliver Mark opens up the workshop doors to reveal some ingenious ideas from a runner-up in last year’s Farm Inventions Competition

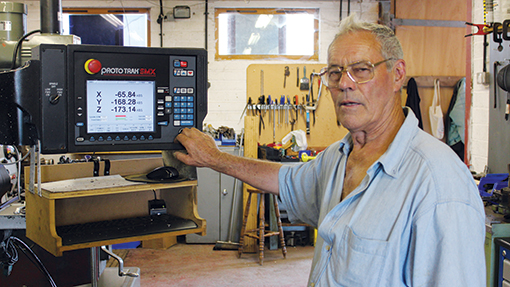

Robin Humphries is a serial inventor. The retired livestock farmer first appeared in Farmers Weekly back in 1997 when his chainsaw mortiser was runner-up in our Inventions Competition.

And in the 17 years since, Mr Humphries has been coming up with clever answers to perennial farming problems on his 115ha farm at Bramshill, Hampshire. Here are a few of our favourites…

Fence joiner

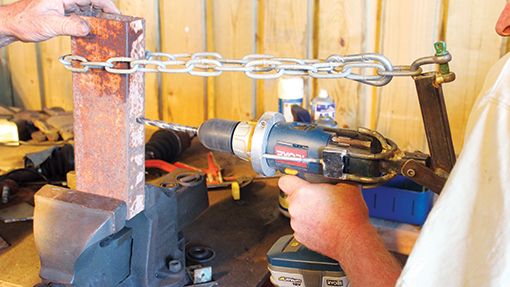

The latest is his 2013 entry – a fence joiner with the backend of an everyday Riobi cordless drill and a series of sprockets and bevel gears leading up to a spinning head at the front.

It’s been three years in the making. The original design involved a comparatively bulky two-handed ratchet before slowly evolving into the one-handed, battery-powered machine it now is. Bevel gears are sourced online and the entire joiner can be assembled for £50.

So, how does it work? With the ends of two lengths of fence overlapping by 150mm and ready to join, the two pieces of wire are bent through 90deg (one pointing upwards, the other pointing downwards).

The machine has a sprag clutch – which uses rollers on an inclined plane to allow the disc head to turn freely in one direction but not the other – to allow the operator to turn the knob, and leading disc head, until the feed-in channel lines up. At this point the two pieces of wire are fed into the machine.

Pulling the drill’s trigger turns the disc head until the two mini anvils mounted on it meet up with the two pieces of wire. Then it’s just a case of pulling the trigger until the wire has wrapped itself all the way round the opposing piece of metal. The faster it turns the warmer the high tensile wire gets and the less draining it is on the 18V battery.

There’s no force required to operate it, either – the machine finds its own centre – and it’ll last several days on one battery.

See also: 12 farm inventions that will change your life

Drill lever

Instead of wearing out drill bits trying to grind your way through vertically-standing shed girders, here’s a handy way of getting a bit of extra weight behind the drill.

The chain simply loops around the girder and a steel arm provides the leverage to get more pushing force behind the drill.

Post knocker

Another novel idea from the Humphries stable was to attach a Bryce Suma post basher to a 6t dump truck, which Mr Humphries picked up for £4,500 with 900 hours on the clock.

The 400 Vulcan attaches to the Perkins-powered Thwaites dumper through a new three-point linkage bracket/headstock made by fabricator Martin Bushnell. The original hydraulic rams are used to lift the knocker ready for road travel and a third was added to act as a top link to crowd the load. Adding an extra spool with a detent for constant flow means everything can be controlled from the paddles on the post knocker.

Cam engine

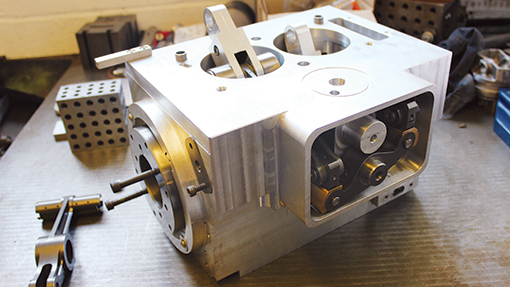

Easily the most impressive piece of engineering on site is the two-cylinder crank-less Shane engine. It uses cams rather than a crankshaft to double the number of combustion strokes for every revolution.

Each piston in the patented motor hits top dead centre every 180deg (or four strokes for each rotation), but there’s no conventional crankshaft for the piston’s big ends to connect to. That helps cut down on size and weight.

Instead, the stumpy con-rods run on an internal cam assembly and only stray 5deg either side of the centre line to improve efficiency.

The shape of the internal cams is designed to replicate the sinusoidal motion of an engine’s piston speed – that means that the piston stops at TDC and BDC and slowly increases/decreases in speed either side of this.

But optimising the shape of the cam to replicate that crankshaft-style motion proved difficult, says Mr Humphries, particularly making the profiles perfect during both induction and combustion (and compression and exhaustion) to keep the piston movements perfectly balanced all the time.

The wire-cut cams are made of hardened tool steel because of its toughness and resistance to abrasion. They are connected to the pistons by rollers at the big-end side of the con-rod.

Robin Humphries wasn’t satisfied with the standard combustion engine so decided to build his own

The cams run on rolled bronze bearings and, at the other end of a pivoting radius arm, push on bronze bearing pads to reduce friction and the wearing impact of both parts.

The radius arm is made of EN 36 steel – the same material as you’d find in most motorcar components – and joins the con-rod’s cam rollers (the equivalent of big end bearings) to the rocker at the other end.

With four strokes occurring in each 360deg rotation, that means the engine produces double the torque of a conventional engine that fires once per crankshaft revolution. So a 600cc engine will produce 60hp and 125ft lb of torque.

Mr Humphries’s engine also has the advantage of a low shaft speed – it means fewer gears are required to reduce the output speed down to a practical ground speed, for instance. It could also be extended to have more cylinders and more power, says Mr Humphries, so it’s potentially more efficient than a con-rod and crank and is similar enough to conventional engines to share many of the advantages they have.

* The last radical change in engine design was the Wankel engine. Its rotary design bought benefits of being simple, smooth and compact, but the teething problems it had when it first hit the market has put major manufacturers off experimenting with new engine designs.