Canadian arable farmer builds his own driverless tractor for £3,000

Fully autonomous farm equipment is something the big brands haven’t yet offered customers to buy, so Manitoba farmer Matthew Reimer decided to save waiting by building his own robotic tractor to pull a grain chaser during harvest.

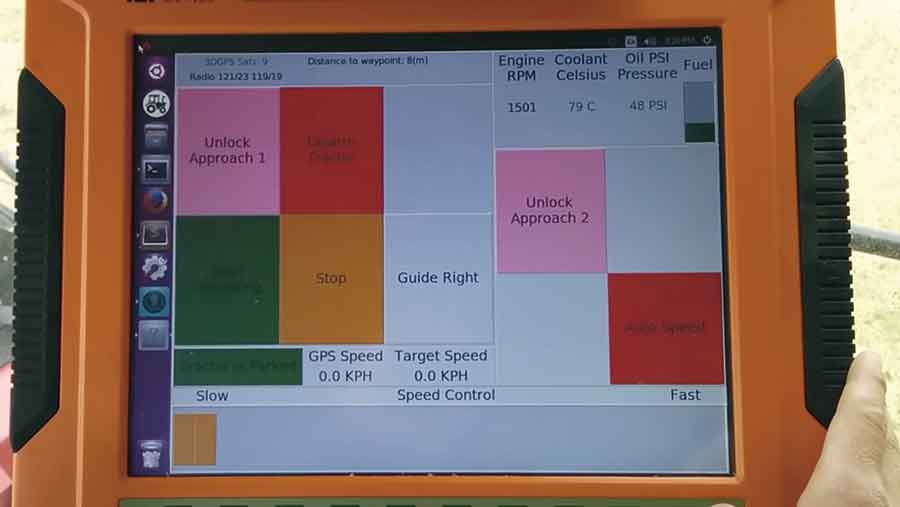

Mr Reimer is able to beckon the tractor and trailer from the combine seat once he’s ready to unload the grain tank.

On cue, the John Deere 7930 wakes up and sets off at a steady speed towards him – the tractor’s CVT box ensuring it can’t stall and there are no complicated range changes.

When the tractor is close enough, it can turn itself around and begin to match its speed with the combine’s.

The rig keeps itself a predetermined distance from the header to keep the auger hanging directly over the centre of the chaser bin.

To fill the bin to the brim, the controls allow Mr Reimer to tweak the speed matching system and pour grain right to the corners of the trailer by nudging the tractor half a metre left or right via buttons in the combine cab.

See also: 590hp articulated Tribine combine goes into production

The reality is that the big players have got similar technology waiting to go, but there’s one small thing that’s holding all of them back – the risk of civil liability if something should go wrong.

So for now, those who want their own robotic high-horsepower tractors will have to follow Mr Reimer’s lead and create it themselves.

In fact, it might be that early adoption and widespread use of field-working robotics on farms will have to begin at the grassroots level.

Developing a remote control tractor

With that in mind, Mr Reimer has started his own small company, Reimer Robotics, to help other farmers develop and install their own robotic systems.

He charges £20,000 ($35,000) for the labour-intensive process of converting a tractor to remote control.

Mr Reimer’s success shows that with the current offering of open-source programming, a little self-directed online learning and the variety of components available on the market, producers could design and implement their own on-farm robotic systems – just as he did.

“My entire project is open source,” he says. “That’s how it started and that’s how it’s going to continue.”

Farm Facts

- Name: Reimair Spraying Ltd, Killarney, Manitoba, Canada

- Area: 1,000ha (2,500 acres)

- Cropping: Wheat, oilseed rape, soya beans

- Tractors: John Deere 7930 w/loader, Case IH 9390, Versatile 875

- Combine: Case IH Axial flow 9230

- Sprayer: Case IH 4230

- Cultivation: 15m Morris Deep-Tiller

- Drill: 20m Morris Contour (10in spacing)

- Chaser Bin: Elmers Haul Master 1150

Open source means the technology is shared by its creators with anyone who wants to use it.

The individual hardware components required to build an autonomous system are widely available and relatively inexpensive.

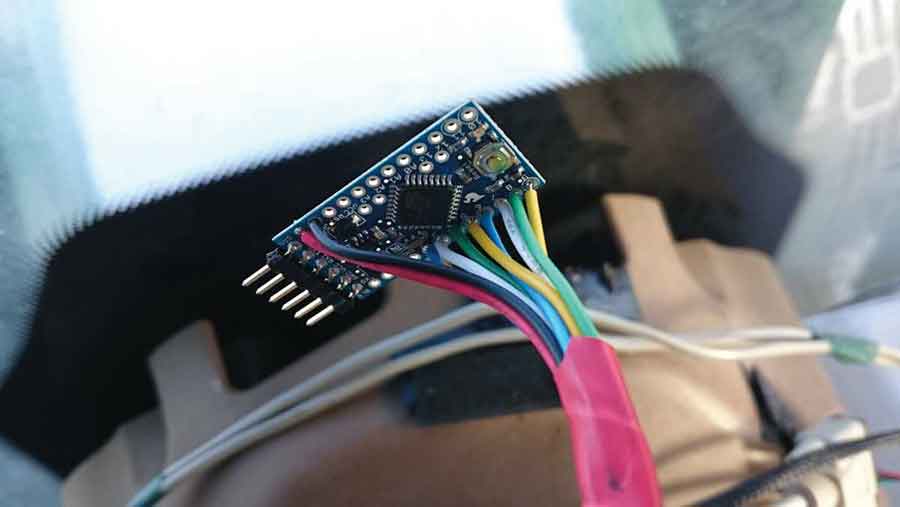

The Pixhawk controller, available online for about £150, is developed for remote control drones and forms the basis of Mr Reimer’s system. The total cost of components built into his system is about £3,000 ($5,000).

“Pixhawk is the autopilot part of an RC drone and formed the basis of my syste. I stumbled across it, and figured that if I can put it in my tractor then I should be able to make the machine drive itself.”

Building the system also required learning a few things about software programming code – the set of instructions used by the system to read and act upon in different circumstances.

Mr Reimer says a basic, free online course taught him to write enough of his own code to make the system work.

“I decided I was going to teach myself from information available on the internet. I found a self-study introductory course in the programming language I thought was going to be helpful.”

Mr Reimer reckons getting the system to do what he wanted actually didn’t take much software code writing – just 600 lines in total.

Safety systems

Currently, the machine is fitted with three fail-safe systems to stop the tractor in the event of a problem. If the radio in the tractor that connects it to the combine loses contact or goes out of its 2km range, the tractor immediately comes to a halt.

There is a stop button on his controller app, and everyone working in the same field with the robot tractor carries a key fob transmitter that can immediately kill the drive.

With a few seasons of real-world use behind it, Mr Reimer has continued to develop and refine his system.

The control modules for forwards, backwards and speed were originally “arduinos” (micro-computers) sticking out of the steering module with all sorts of wires tangled in the cab. It’s now a neat system that sits in a box on the floor and can be easily removed when it’s not needed, making the whole thing much tidier.

In the combine, the controls have been updated to a tough tablet computer to make the app he created much easier to use. He’s also added a host of extra adjustments and features, including a tractor monitoring system.

What’s next?

“I plan to map ditches and where the combine hasn’t gone to prevent the tractor from going there,” he says.

“I’ll add more safety features, too. Right now there’s no sensor on the front, which would allow the tractor to detect an obstruction and stop on its own.

“I’d also like to build a smartphone app for the artic driver, so he doesn’t have to get out of the truck to unload the tractor and can start the pto from his phone.”

Even though his goal is to create machinery that can work without a driver, he believes having a human in the field to keep an eye on things remains a critical component. He calls his concept ‘supervised autonomy’.

Mr Reimer also expects to expand the kind of work his robotic tractor can do, focusing next on pulling a set of rolls over seeded soya bean fields. He’s already had it on a snow-blower, controlling the machine from inside the house while it was clearing the yard.

“It’s crucial that more farmers get involved in developing technology. All the code and instructions can be found online, but if you make something that could be useful for others, don’t forget to share it with the world by posting it on the internet.”