Why a spring spike in dead lambs occurs despite vaccinations

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener A spike in pasteurella in dead lambs, aged five to eight weeks, has been seen again this spring despite farmers vaccinating ewes for the disease.

Typically found in northern England in May, the spring spike is due to a gap in immunity. Further south, or with earlier lambers, the spike is seen in April or sooner.

The immunity gap is a vulnerable period in-between colostral immunity ending and subsequent vaccinations taking effect (see graph, below).

This year’s spike is a good reminder to progress with pasteurella vaccinations in good time, and to start protocols when lambs are three weeks old to shorten the immunity gap.

See also: Lambs born in early spring at risk of nematodirus

Why this year?

This year’s dry weather conditions – endured by grazing livestock in April and May – have impacted on grass growth rates and, therefore, likely to have affected ewe milk yields (which peak at around four weeks post-lambing).

This may have led to lambs which aren’t as full of milk and, therefore, more prone to chilling during cold nights.

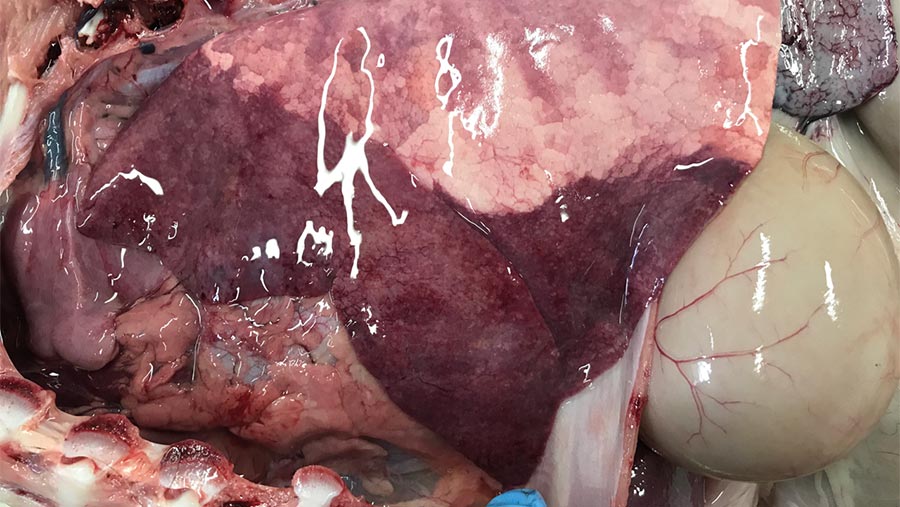

This could explain why more cases of pasteurellosis in lambs aged five to eight weeks have been seen this year. At post-mortem examinations, lambs have pleurisy and/or pneumonia.

Pleurisy caused by pasteurella. © Farm Post Mortums

Immunity gap

Maternal immunity from the vaccines (given to the ewes before lambing) lasts three to four weeks, and lambs cannot be vaccinated until they are three weeks old.

Lambs remain vulnerable and unprotected by any vaccine until five days after a booster dose is administered, four to six weeks after the first dose.

This means lambs are unprotected from three to eight weeks of age.

The graph below shows the seasonal trends in the incidence of pasteurellosis in lambs, as diagnosed by Farm Post Mortems over the past four years.

Disease facts

Pasteurellosis: What you need to know

- Caused by bacteria (Mannheimia haemolytica and Bibersteinia trehalosi) which live in the throat of healthy lambs and can suddenly “wake up”.

- Bacteria become active if lambs are stressed by bad weather or disease, such as worms.

- Kills lambs through septicaemia (blood poisoning) or pneumonia, and can cause mastitis in ewes.

Pneumonia caused by pasteurella. © Farm Post Mortems

Clostridial diseases: What you need to know

- Clostridial diseases (mainly pulpy kidney in older lambs) are caused by toxins produced by bacteria which live in the soil and in lambs’ guts. Importantly, the organisms responsible are present on all farms.

- Colostral antibodies last a bit longer for clostridial diseases (10 weeks or so), and lambs can be vaccinated from two weeks old.

- The vaccine comprises two doses one month apart and will last a fat lamb until slaughter, so the earlier you do it the better.

Steps to protect your flock

- Note down timings for vaccines and boosters in your calendar or flock health plan.

- Administer doses as required – start as early as possible.

- Operating short lambing periods, or managing lambing in batches and grazing in subsequent batches, can help in the timely administration of vaccines.

- If buying store lambs or keeping your own over winter, make sure you know when to administer their third dose of the vaccine. Vaccines give three months’ cover.

- Check the type of vaccine you are using – some only do clostridials, some only do pasteurella. However, there are two options available that do both.

- Lambs that are still kept in autumn can succumb to pulpy kidney. Make sure lambs are protected long before any dietary change, as this is caused by a toxin produced by clostridial bacteria in the gut after a sudden rush in energy and carbohydrate. Store lambs can experience this when introduced to creep, good root crops or a late autumn flush of grass.

Ben Strugnell is an independent vet in County Durham. Ben worked in mixed practice in North Yorkshire for five years, specialising in farm animals.

He then went on to work for the Veterinary Laboratory Agency in Thirsk, where he developed his skills in pathology and his belief that an accurate post mortem can diagnose the majority of diseases in farm animals and can prevent unnecessary losses and improve productivity on farm. He now runs the Farm Post Mortems service.