A poultrykeeper’s guide to ground-source heat pumps

© Adobe Stock

© Adobe Stock With farm carbon emissions under the spotlight and an increasing emphasis on sustainable agriculture, many producers are moving away from fossil fuels.

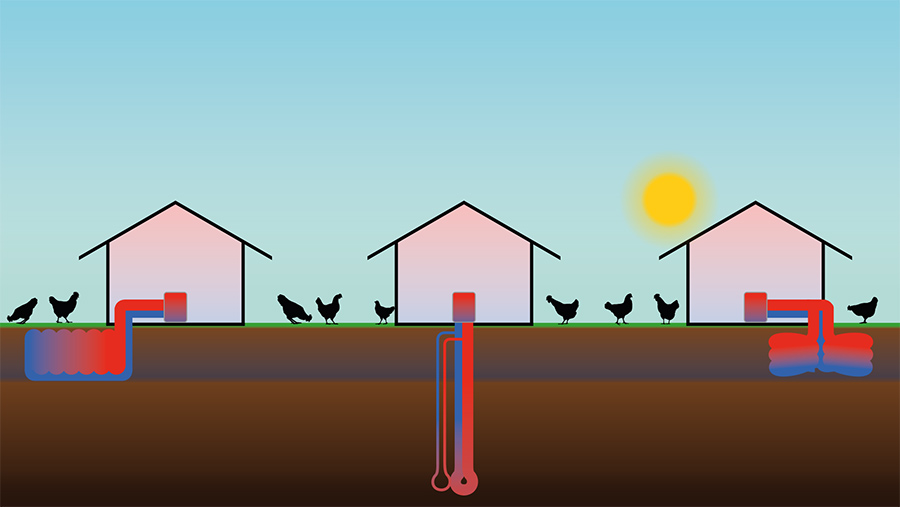

Ground-source heat pumps offer a good solution for poultry units, with a low carbon footprint and the advantage that they can cool as well as warm spaces to keep a flock at the ideal temperature, whatever the weather.

Initial investment costs are high but they have a long working life, are relatively cheap to run and attract a government incentive, all of which makes them an increasingly popular choice.

See also: 4 key actions to help manage poultry flocks in hot weather

How do they work?

Ground-source heat pumps use long water pipes, buried in the soil in a zig-zag pattern, which transfer heat up or down a temperature gradient in a series of steps:

- Water in the pipes absorbs heat from the surrounding soil – even in winter it will be warmer than the ambient temperature

- A mix of water and antifreeze in the pipes passes over a heat exchanger

- Heat then transfers into a refrigerant

- A compressor increases the temperature further

- A second exchanger transfers the heat to the poultry heating system

- With the heat extracted, cold water returns to the ground

Open-loop systems work by circulating water direct from a source such as a borehole or surface water. Pipes can be laid in various horizontal and vertical configurations in the ground.

Chris Davidson, director of heat pump designer Genius Energy Lab, says the system is based on simple technology.

The heat pump can be used to raise temperatures from about 12C up to 40-60C.

The whole process can also be reversed at any time and used to cool sheds – or even provide heating and cooling simultaneously.

“It is particularly useful in agricultural systems where high temperatures in the summer and low temperatures in the winter are a problem,” he says.

Benefits to farmers

“Poultry farms are mainly off the gas grid, relying on liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and oil which are both expensive and highly carbon intensive,” says Mr Davidson.

“Conventional heating equipment also generates on-site emissions, for example nitrous oxide and sulphur dioxide, which has air quality considerations.”

Biosecurity is another concern when oil or LPG needs to be delivered to the site.

As ground-source heat pumps run on electricity, there are no deliveries to organise, and producers are not exposed to oil price fluctuations.

Running costs are generally 25-50% cheaper than conventional equipment, depending on the displaced fuel and current market price, while carbon dioxide emissions are reduced by about 75%. As the electricity generating network is decarbonised using renewable energy, this proportion increases year on year.

The underground system means that there is no external piping which can be damaged.

Unlike conventional boilers, the heat delivery is less prone to fluctuations, which is better from an animal welfare point of view, says Mr Davidson.

Planning and potential pitfalls

Installing a ground-source heat pump is usually allowed under permitted development rights – in some cases, a planning application may be required but councils don’t tend to object.

The land requirement depends on how much heat is needed – the greater the heat, the larger the area.

A 10kW system would need two 100m boreholes or about 200m of horizontal trenches, but this is dependent on geology.

The pipework is buried below plough depth so once it is installed the ground can be drilled and cropped as normal.

It’s important to check the existing heating system for compatibility and seek professional advice over land contamination when any excavation is undertaken, warns Mr Davidson.

Professional advice may also be needed if the location means groundwater rises to the surface on its own, as it can be difficult to control.

Installation and maintenance

Installation can take from a few days to several weeks depending on the size of the system and any site limitations or obstructions. “It is very straightforward on farms, because the land area is generally available,” says Mr Davidson.

Maintenance will almost always be less than that of a conventional boiler system, with most installers offering annual maintenance packages.

It’s a durable technology which could be in service for 100 years. The pump needs replacing every 20-25 years this should be easy to connect with the existing system.

Costs and return on investment

The Renewable Heat Incentive available from the government pays per unit of heat generated – creating another possible income stream.

Eligible installations can receive quarterly payments over 20 years in line with the amount of heat produced. “Depending on size of system, claims can be a few thousands to hundreds of thousands of pounds,” Mr Davidson says.

The typical return on investment is three to seven years including RHI payments. “It’s very project-specific – the bigger the project the quicker the payback generally,” he says.

Typical costs

Installation

A 100kW system will cost between £80,000 and £160,000 depending on the type of ground loop involved. In agriculture, and assuming there is land available, it should be at the lower end of this range.

Running cost

Comparisons are difficult, particularly with fossil fuel prices being so volatile at present. However, costs should be between 25% and 50% lower, depending on existing fuels and fuel costs.

Case study: Fir Tree Farm, Cumbria

Richard Storr installed a ground-source heat pump at Fir Tree Farm, near Silloth, Cumbria, in 2019, when he added a 50,000-bird broiler shed to his existing dairy business.

“I wasn’t a fan of biomass boilers because I was worried the pellets would go up in price,” he says. “Although the capital investment was more, we decided to go down the ground-source heat pump route.”

IPT Technology recommended a 400kW system which was larger than Mr Storr had expected. “But now we’re up and running I wouldn’t like to have had a smaller one,” he says.

“The plant and heat pump infrastructure are reliable and fairly maintenance free so far.”

Installing the ground loops at Fir Tree Farm © Richard Storr

The ground-source heat pump is used for both heating and cooling the shed depending on the season, and using it has been a steep learning curve, says Mr Storr.

“It does take longer to heat the shed before placing the birds, but once you have got your head around that and how to use it, it is a consistent and gentle heat, which is important.”

This helps with litter management, too. “Comparing myself to other farmers I know my litter is good – it’s easy with the ground-source heat pump to keep a decent litter.”

The total installation took six months. “It wasn’t bad to install – the GeoCube plant room came already built. We had to install the ground loops, we had the pipework and radiators fitted, then it was all joined up,” he says.

The biggest challenge was the delay in receiving the RHI payments. “I didn’t realise how long it would take to become accredited. There were six to seven months before we started receiving the RHI.”

This meant he initially had to pay for the electricity to power the pump without RHI support. “That took a lot of propping up – I hadn’t anticipated such a long wait.”

The return on investment should be four years, but electricity prices will affect this, he says. “When we installed the system we were looking at 10p/kWh but now we’re at 15p/kWh which does have a big impact on the payback time.”

He advises that anyone considering a ground-source heat pump should ensure they can justify the initial capital investment, even with the RHI. “It costs a third of a new broiler shed just to put the heating system in, so you really need to think it though.”

Farm facts

- 47ha

- 45,000 Ross 308 birds

- Supplying Frank Bird Poultry

- 80 dairy cows

- 400kW GeoCube closed-loop ground source system

- RHI over 20 years – paid 9.68p/kWh for April 2020