How genomics could benefit even top-ranked dairy herds

Genomic testing of dairy cows can lead to significant improvements in production and a return on investment, a pilot study on one of the UK’s top herds has found.

For the Chalcyffe herd of pedigree Holsteins owned by JF Cobb and Sons in Dorset, you might think genomics wouldn’t have much to offer such a well-performing genetically strong herd.

However, even though the herd is ranked in the top 1% of UK profitable lifetime index-recorded herds and is producing on average 12,500 litres a cow a year, genomics has been found to have significant cost benefits.

See also: How farmers can use genomics to improve breeding

Nick Cobb was involved in a study with RAFT Solutions, a veterinary owned business working with Zoetis and their veterinary-led genomic test Clarifide.

More than 400 calves were genomically tested and were followed through to their first lactation. Fertility and milk yield were the main focus areas.

Working with RAFT partner Mark Burnell from Synergy Farm Health, the duo wanted to see whether genomic testing of females would stack up on the farm.

Mr Burnell says: “We know the reliability of genomics is far greater at about 55-70% compared with 15-35% when basing breeding decisions on parent averages.

However, we wanted to find out exactly what the financial benefits were and whether you can get a return on your investment.”

With each genomic test costing about £30 including some consultancy advice, it was important the financials stacked up.

How it worked

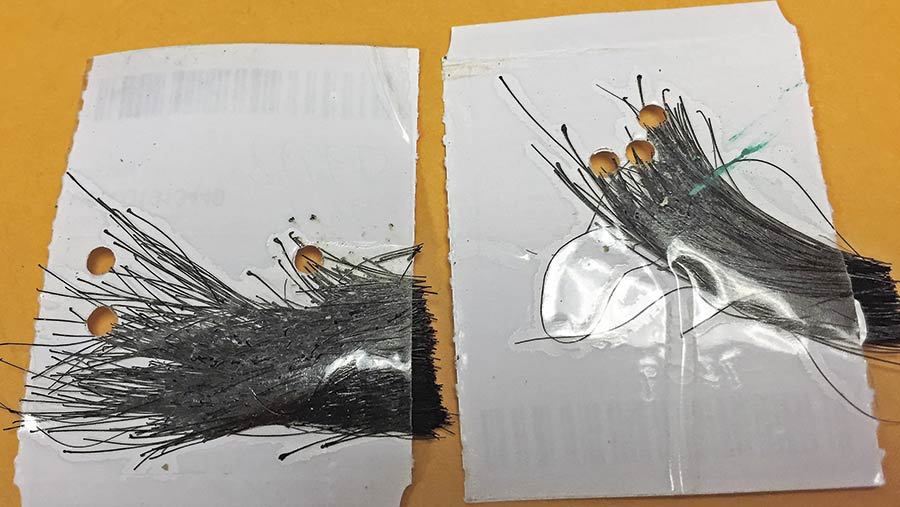

A hair sample from the tail of calves involved in the study was taken at birth and sent off for testing.

Genomic testing looks for markers in the DNA of each animal, which are linked to certain production and health traits. Results were then fed back and animals were ranked according to different traits.

Mr Burnell says the key to maximising genetic improvement is to ensure the most reliable method of predicting the genetic merit of an animal is used when making decisions about which animals to keep for replacements.

With heifers costing about £1,500 to rear, you can save a significant amount of time and money while also speeding up genetic progress Mark Burnell, Synergy Farm Health

He argues genomics offers a far greater reliability when making those decisions compared with just using parent averages (PA), because predictions can be made from one-day-old with up to 70% reliability.

“This means you can make a decision early from which animals to breed, so you can drop out the worst 10% of animals.

With heifers costing about £1,500 to rear, you can save a significant amount of time and money while also speeding up genetic progress,” he adds.

Results: Genomic profitable lifetime index

Results from genomic testing revealed the top heifer tested had a genomic profitable lifetime index (GPLI) of £516.

The worst had a GPLI of -£121, resulting in an expected difference of more than £1,200 profitability between the two animals over their lifetime.

“By knowing accurately which heifers Nick wanted to keep, he could potentially maximise the beef output from the farm by breeding ‘bottom end’ heifers to beef. Sexed semen could then be used on the top genomically performing heifers,” explains Mr Burnell.

Results: Milk yield

Results also showed the top 1% of Chalcylffe animals based on their genomic predicted transmitting ability (GPTA) milk figure went on to have a mature equivalent milk yield some 5,000 litres higher than the bottom 1% of animals.

The difference between the top 10% and bottom 10% of animals was more than 2,700 litres.

However, if PAs were used to predict milk-yield performance, the difference between the top 10% and bottom 10% was only 1,800 litres.

Due to more accurate rankings when using genomics, if Mr Cobb deselected the bottom 10% of animals based on parent average figures for milk, then this would result in a potential loss of more than 50,000 litres (mature equivalent milk litres) across one lactation.

This is compared with if he deselected animals from the bottom 10% using the genomic predicted transmitting ability milk figures, because genomic figures, which are more accurate, showed these animals would have produced more milk.

Nick Cobb © Peter Dean

Results: Fertility

Even more startling was the power of genomics in predicting fertility.

When heifers were ranked by their genomic predicted transmitting ability (GPTA) fertility index, those animals in the bottom 10% took, on average, 42 days longer to conceive than those in the top 10%.

However, PA PTAs proved to be far less accurate than genomic PTAs for fertility at predicting future fertility performance.

The top 10% of animals ranked by PA fertility index were predicted to have an average calving to conception of 22 days less than that of the bottom 10%, almost half of the difference seen when ranking the animals by their genomic result.

Results: Financials

In terms of financials, it is clear the cost of testing (approximately £30 per animal) represents a shrewd investment, says Mr Burnell.

“If you selected heifers for milk yield using PAs instead of genomic figures, then for this set of animals, the potential loss was 51,985kg of milk, which at a milk price of 27p/litre equates to a potential milk loss of £14,046 by deselecting the wrong bottom 10%,” he says.

Likewise, for fertility, there’s the potential for an extra 550 days cows are not in calf when using PAs compared with genomics.

At a cost of £3.50 for every day a cow is not in calf, this is a loss of £1,925 if selecting the bottom 10% of animals by PAs.

Mr Burnell says the savings are probably an underestimation as only two traits were examined. “It also doesn’t take into account savings realised across multiple lactations, as well as the value of the genetic potential of the animals retained and the improved genetic merit that will be passed on to subsequent generations,” he adds.

When to use genomics?

However, not all farms will benefit from the use of genomics and they should be used with care, warns Mr Burnell.

He says management of calves need to be good and the environment right to allow the genetics to express themselves. “There’s no point investing in genomics if calf mortality is high,” says Mr Burnell.

Good records are also required, so you know what is happening on the farm and whether breeding decisions are working.

Farmers thinking about using genomics need to test all the heifers on the farm. “If you start guessing which ones to test, then you are ranking them before you have even tested them. You could run into problems doing that,” warns Mr Burnell.

Farmer comments

Mr Cobb believes genomic data have a place in dairy herds. “As more of this technology is used and the relative cost reduces it will become the norm.

When purchasing animals in the future farmers will not only enquire about the animal’s health status but also ask for its genomic test results,” he says.

“Genomics has given me a good feel to how my animals are performing. We have a lot of animals in the top 1% and it is a good tool to select which animals to breed from.

“The skill for the breeder now becomes choosing the correct traits and indices to suit the given production system,” he says.

Getting to grips with genomics terms

Genomic testing Genomic test results are more reliable than traditional parent average values (typically 50-70%) as they reveal more about the genetic potential an animal actually inherited from its parents.

Using genomic testing, a heifer’s genetic potential is revealed early in life, genetic progress can be accelerated and herd profitability can be enhanced by capitalising on improved performance across a number of traits.

Genomic profitable lifetime index (GPLI) is commonly used to refer to profitable lifetime index (PLI) for genomically tested dairy animals. PLI is a weighted index of individual trait genetic merit.

Predicted transmitting ability (PTA) is the predicted difference of a parent animal’s offspring from average, due to the genes transmitted from that parent. Each PTA is given in the units used to measure the trait.

Parent average Average of the PTA of the two parents.