What’s in Your Livestock Shed? visits a £1.36m robotic dairy

Agri-EPI Centre opened the doors of its state-of-the-art £1.36m robotic dairy unit in Somerset last week.

Farmers and allied industries were given the first glimpse of the highly anticipated South West Dairy Development Centre last week (2 October).

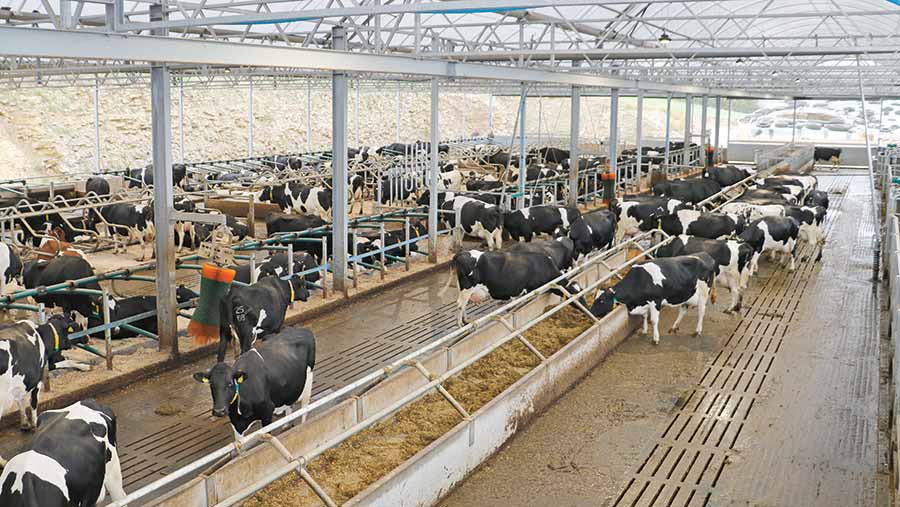

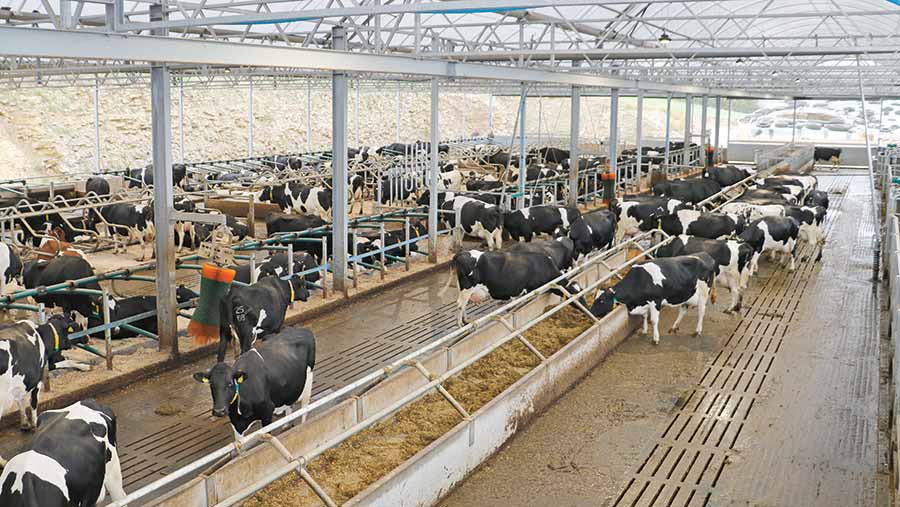

The 180-cow building is the first of its kind in the UK and features three robotic milkers and an automated feed kitchen, as well as an array of other precision technology.

Once fully stocked, the autumn calving herd of Holstein Friesians will be grazed outside on a three-paddock rotation using specialist imaging and satellite data to monitor grass growth and quality.

See also:What’s in Your Livestock Shed? visits a state-of-the-art £1.3m dairy unit

Located near the Royal Bath and West showground at Beard Hill Farm, Shepton Mallet, the site, alongside a 42ha grazing platform, is being rented from Steanbow Farms on a 15-year tenancy agreement.

Costing £7,500 a cow place, the build was established in close partnership with independent dairy specialists Kingshay, who manage the facility.

It was funded by the Department for Business Innovation and Skills – through Innovate UK, a technology and innovation agency – as part of its Agri Tech strategy.

It is one of three Agri-EPI dairy sites in the UK – the other two include a second robotic milking unit located at Harper Adams, Shropshire, and youngstock facilities in SRUC, Dumfries.

The aim is for the site to become a test-bed for new technology and research. Primarily, researchers will explore how dairy farmers can harness robots to overcome the huge labour challenge currently facing UK agriculture, while simultaneously exploiting grass to reduce the impacts of price volatility.

The unit is one of three test-beds for the DCMS-funded 5G Rural First project, which is examining the potential of the improved connectivity offered by the next generation of mobile signal.

Agri-EPI Centre project manager and director of dairy and research at Kingshay, Duncan Forbes, has been instrumental in the development. He gave us a guided tour.

The shed

Built by Dutch company ID Agro, the shed measures 90x28m and is the first of its kind in the UK.

Its translucent fabric roof is black on the outside, has a carbon fibre mesh middle and is white on the inside, which means it transmits 20% natural light. It has a lifespan of 15 years.

Being lightweight (it weighs less than 5t) means less steel uprights were required during construction, which reduces its environmental impact and impinges less on the cow environment.

A Galebreaker curtain along the front of the building is controlled by a rain sensor, humidity monitor inside the building and anemometer, which measures wind speed. The curtain adjusts from the middle, top and bottom of the side to provide optimum conditions.

There is no ridge ventilation, but good cross-ventilation is provided due to the fact the roof is 5m to the eaves with mesh archways at shed ends providing air outlets, says Mr Forbes.

Flooring and cubicles

The floor is made from grooved concrete and has a 1m-deep slurry channel running down the middle of each passageway.

Rubber matting is provided around the feed area to maximise comfort and intakes.

A robotic slurry scraper scrapes half of the passageway at a time, pushing the muck into the middle of the passageway and through the slats.

Each channel contains a series of weirs to retain fluid so that once the slurry is deposited into the channels it floats on top of the fluid reservoir and is carried out of the shed and into the slurry store, which can hold up to seven months’ worth of manure.

There are two types of cubicles installed at the unit: the Kingshay K38 cubicle, where the neck rail is correctly positioned by means of the unique 38deg top rail of the division, and Easifix plastic ones, which give when the cow pushes against them.

© Peter Dean

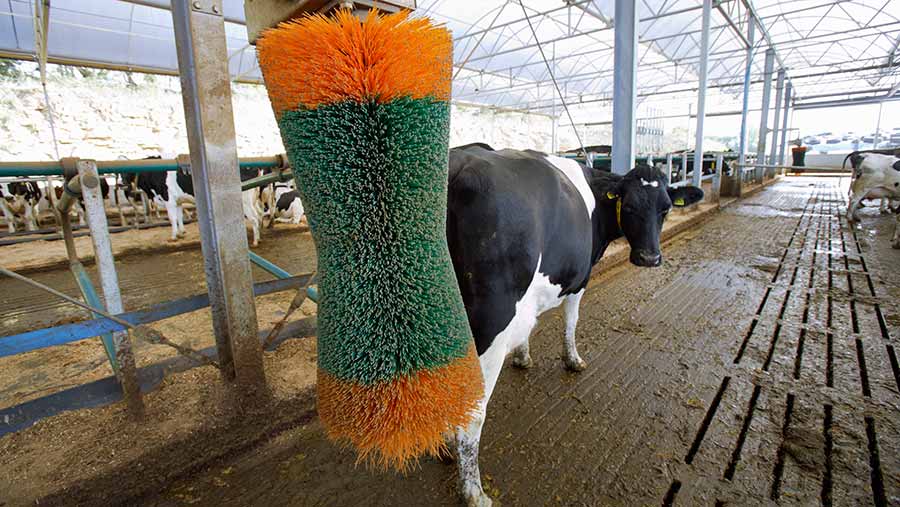

The shed comprises two single rows and a double row with Easyfix mats topped up with sawdust to maximise cow comfort. Alongside this they also have three cow brushes.

© Peter Dean

Grazing platform

Cows are currently fully housed but from next spring they will graze a 42ha platform moving between one of three zones (A, B and C) every eight hours. The furthest distance cows will have to walk will be 650m in each zone.

As part of the 5G Rural First project, researchers will be trialling a hyperspectral imaging camera technology to measure grass covers from the air.

The camera uses different wavelengths of light to identify dry matter covers, energy and nitrogen content of grass to allow better allocation of nutrients and buffer feed.

This will be used in combination with collars that transmit cow location and rumination data, so researchers can deduce which areas of the grazing platform are more productive and preferred than others.

Segregation gates and grouping

A trombone gate allows cows access to a race near the robots. Once inside the race, cows will come to three segregation gates that give them access to different areas of the shed:

- Gate 1: A two-way segregation gate that either turns them straight on down the race to more gates, or right, to be milked, if they have permission.

- Gate 2: Turns them one of three ways: to the high-dependency unit that consists of calving pens and sick pens, straight on down the race or left to the milkers feed area.

- Gate 3: Gives cows access to grazing straight ahead or to a dry-cow feed area on the left, located beyond the milkers feed area, where a non-return gate allows dry cows access to cubicles but doesn’t allow milking cows to access the dry-cow ration. This means all animals can be housed together regardless of their stage in lactation, which reduces stress.

There are three GEA Monobox robotic milkers. Touchscreen display allows users to access to milking data such as milk yield and quality in real-time.

Attachments are taken off as each quarter milks out to offer optimum results.

© Peter Dean

Feed kitchen

A ‘feed kitchen’ has been built on to the side of the shed opposite the silage clamp.

© Peter Dean

Feed is loaded using a sheer-grab on to one of three ascending elevators at a time. Each elevator delivers one of three forages (grass silage, maize silage or alkalage) into its bunker at the top. This takes just 30 minutes a day for one person.

The rest is all completed robotic, with ration requirements programmed using a computer.

A rail-mounted mixer feeder parks underneath each bunker where the correct amount of feed is deposited. Minerals are added through an auger and concentrate from two feed bins fitted with weigh cells. These are linked to the feed mill to alert them when supplies are low.

Once the load is completed, the mixer then backs on to a motor, where it is mixed for about seven minutes.

The box then travels around the shed on a rail delivering fresh feed 15 times a day. Three partial mixed rations are provided: dry cow, milker and transition.

The kitchen is completely bird-proof, with roller doors to prevent contamination.

How affordable is it to other farmers?

The system is being lamented by researchers as the future of the dairy industry, but in actual fact it could set an average dairy farmer back by up to £10,000 a cow space.

For a 180-cow dairy that could cost a farmer £1.8m – nearly £500,000 more than this project cost.

“There’s no doubt we have benefitted from manufacturers giving us good discount,” explains Mr Forbes.

“Because they have wanted to be involved with this for research purposes and clearly for the profile it is going to offer them.

“But we had to go out there and fight hard to get a good deal to maximise the return on the grant,” he says.