Advice for dairy farmers considering robot milkers

Robotic milkers are becoming increasingly popular, now accounting for half of all new UK installations, but there is much to consider before investing.

Combining robots with grazing

It isn’t difficult to set up a system that allows cows to be turned out to grass and still achieve three visits a day to a robotic milker, says dairy consultant Jonathan Jones.

And it should enable high yielders to be milked four or five times and low yielders once or twice.

See also: Robot milker demand to surge, say farm lenders

“High yielders visit the robot around midnight and again before they go out to grass in the morning and then come back voluntarily into the buildings to be milked a third time around midday.

“In the afternoon cows tend to lie in the cubicle housing and will visit the robot again before going back out to graze in the early evening.

“On average at least three milkings a day can be achieved on a grazing system,” says Mr Jones.

During the first six weeks of the lactation, cows on robotic milkers tend to be fed on a fixed rate.

“The robot will deliver one feed rate for the first 25 days and then at a higher level for 25-40 days. Mid-lactation can be a problem in some cases as cows get lethargic and visits to the robot decline.

“Those cows that are eating less and producing less milk, visit the parlour less frequently. If you fail in your management of cows at this stage of lactation, milk yield can fall away quite quickly and cows end up only going to the robot once a day. So I would urge anyone contemplating robots to be aware of this stage of their cows’ lactation to ensure no production is lost,” says Mr Jones.

A typical robot daily delivery of concentrate for cows on an “uncomplicated” TMR mix would be 10kg for the first 25 days and 12kg to 42 days, after which they would be fed to yield.

“But it’s important to offer a highly palatable ration. Palatability and energy are important considerations for feeds offered through robots and need to be at least 13MJ/kg DM metabolisable energy. Vitamins and minerals can reduce the palatability of concentrates so be aware of that if you are switching to robots.”

What to think about

- Consider the distance between the milker and the furthest point of grazing. Is it an acceptable distance for cows to walk?

- Cows often return to buildings in groups, so cow flow is even more important when cows are at grass. One-way gates at the building entrance and selection gates at the exit to pasture can be useful.

Shed design and layout

When installing robots it is vital to consider whether your long-term goals will call for any future changes to buildings and infrastructure. If herd expansion is likely it’s important to consider what robotic capacity will be required and how the layout of the buildings can be most effectively adapted.

Use Google Earth to take a bird’s-eye view of how all areas of the system of the farm are laid out – cubicle accommodation, silage stores and slurry storage. Future expansion plans in terms of infrastructure can then be undertaken with a more balanced and long-term vision using this approach.

Consultant Tim Gibson says robots need to be positioned about 20ft from the nearest obstacle – say a water trough – but ideally cows need to be passing the robots en route between the housing and feeding areas of the building.

“There’s been a severe shortage of information available to dairy farmers about how many of the practical issues concerning switching to robots affects herd management,”says Mr Gibson.

“Advice to farmers on practical issues such as where robots should be positioned for the primary benefits of the cows has been lacking. It’s the cows that come first every time.”

Dairy farmers installing robots must also be mindful of lighting. There must be adequate illumination in the shed to ensure cows can easily see the robots and that they are visible to the cows from all points is in the building.

“If the robots are in a slightly elevated position so much the better,” says Mr Gibson.

“When a cow is in the robot she is on her own and she needs to feel safe, unthreatened and comfortable.”

And the feed offered in a robot also needs to be considered. The main energy density of the compound fed in robots should be higher than that fed outside the robot.

“Cows are compelled to go into a robot for an energy-giving feed, not for protein. This highlights the benefits of the free-access system.

“In a forced-access system it’s possible to get away with feeding a lower cost ration – say a TMR mix – but you have far more control over feeding cows according to yield by not cutting corners on the cost on the diet fed in the robot.”

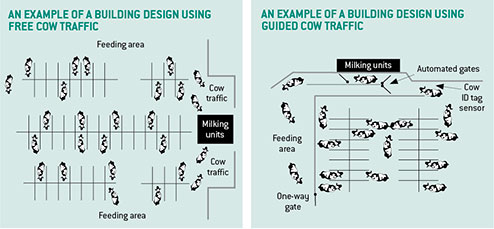

Free v guided access and number of robots required

One robot arm is required for up to 70 cows in milk, which equates to up to 85 cows a station based on 20% being dry a year-round calving situation.

A free-access system enables cows to voluntarily go to the robot to be milked whenever they decide to do so. In contrast, a guided access system is more costly in terms of the infrastructure required, because it “channels” cows to the robots within the housing layout.

Yorkshire robot consultant Tim Gibson says: “If robots are going to be looked on as a high-welfare system of managing high-yielding dairy cows I think free-access robotic milking is the way to go.

“Cows have the ability to be milked when they want and are not forced; the guided systems channel the cows towards the robots so there’s a degree of forcing the cow to be milked,” he adds.

Another option with guided traffic is when there are pre-selection gates that select cows that are ready for milking while on their way to the feeding area.

Lameness management

A strict policy on lameness should be adopted for herds on a robotic system to ensure cows aren’t suffering from foot problems that could deter visits to their robot.

“It’s just as important for cows on robots as it is in a conventional system and requires vigilance on the part of the herdsman to make sure cows are being treated.

“But there is an issue over foot-bathing and the ability to effectively and accurately foot bath every animal in the herd as a routine treatment,” says consultant Tim Gibson.

One option is to let cows go out of the cubicle house into a holding area, say once or twice a week, so they have to go through a foot-bath. But Mr Gibson says farmers should use a really good-quality foot-bath treatment.”

Having a foot-bath in close proximity to the robot isn’t recommended. “I’ve experimented with various systems on our own unit, including foot-bathing on exit from the robot and even foot-baths positioned around the robots.

“But it can be a deterrent to cows and that’s what any robotic system must avoid. And a bath can become a reservoir for disease as it fills with slurry so don’t use the robots as a treatment area.”

Staff management

Yorkshire robotic milking consultant Tim Gibson says all too often staff are attracted to working on robot systems because they see it as an easy option. But that’s far from the case, he warns. “Staff working in herds milked by robots need to have a different approach to the way cows are looked after in a conventionally milked herd.”

They must be diligent and be able to develop new management skills that can process and react to the data and information that the robot presents on screen. He believes that if the drive to buy robots is to save or minimise labour the decision needs to be carefully considered.

“In most cases where the person writing the cheque out for the robot is not the person who is hands on working with the cows, there are issues which can cause robots to be taken out or work poorly.

“Robots being forced on to staff with the instruction of fewer hours, overtime pay or relief help coming in, tends to create negativity and problems. If the person who buys the machine is running it, they make the effort for it to work and then it will save labour.

“And depending on current employee’s remunerations, it needs to be considered if standby pay will have to be paid or if staff are willing to renegotiate terms.”

A 250-cow unit can be run by two men with ease when using robots to do the milking, reckons Mr Gibson.

“But bear in mind robots must be compared with three-times-a day milking to give a fair comparison. So when milking 250 cows three-times-a-day there would probably need to be four full-time workers.

Where fewer robots are working – say in the single robot 60-80 cow herd – the halving of labour requirements isn’t achieved as easily. But the flexibility they offer can be a bigger boon.

“Most smaller farms are happy with the flexibly the robot brings as well as the cow health benefits. To put it in perspective, the value of the whole family being able to attend weddings without having to rush back to milk is something you can’t put a price on,” says Mr Gibson.