Analysis: How the national living wage will hit the horticulture industry hard

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener The UK’s horticulture sector wakes up today, Friday 1 April, to what some predict will be the biggest upheaval in a generation – the introduction of the national living wage (NLW).

With labour bills typically accounting for 35-60% of turnover and profit margins for many at about 2% of turnover, few sectors will face such a big challenge to remain profitable following the introduction of the national living wage (NLW).

The changes create a new age band, pushing workers aged 25 and over up from the national minimum wage (NMW) of £6.70/hour, to the NLW, at £7.20/hour.

From there, the living wage will rise rapidly – by 7% each year – until 2020, when the government has said it wants the rate to be equivalent to 60% of median earnings, which at current wage growth could take it to £9.15/hour or higher.

Labour cost increases will be even greater in Scotland, where banding by age does not exist for agricultural workers, meaning younger staff will also qualify for the new higher rate (see “The challenge to Scotland” box, below).

Growers say they are not opposed to the uplift in wages in principle – as well-known farmer Guy Poskitt pointed out at the NFU conference in February, most would struggle to live on the minimum wage.

But, having been given just nine months’ notice (the chancellor announced the changes in his Summer Budget last year), businesses are struggling to cope with the speed of change.

“Many are extremely concerned about how their businesses will continue to survive, let alone have money left over for investment and innovation in this highly competitive and fast-paced sector,” says Lee Osborne, NFU employment and skills adviser.

Cumulative impact

Growers had been planning for a 2.5% uplift in wages – the average rise in the NMW for the past few years. The 7% year-on-year rise, plus the associated increase in national insurance contributions, had not been planned into business budgets.

See also: ‘Catastrophic’ wage rule threatens growers’ livelihoods – NFU

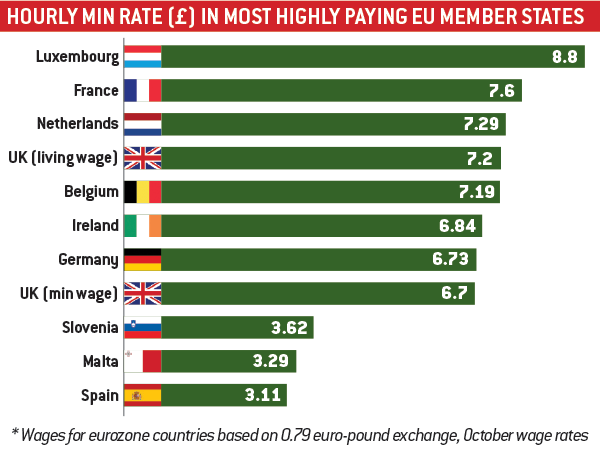

The changes represent a 35% rise in wages for older workers over the next five years in addition to the 11% uplift from the introduction of the NLW itself, and makes the UK the fourth most expensive place in the EU to grow fruit and vegetables.

Unless businesses manage a dramatic change, profits are likely to be wiped out by year four of the NLW, according to a report conducted by business consultant Andersons and commissioned by the NFU. This could be even sooner for businesses operating on margins smaller than 5%.

|

Labour costs per worker – national living wage v national minimum wage (£) |

|||||||||

|

|

National minimum wage (21 year-olds upwards) |

National living wage (25 year-olds and upwards) |

Additional cost of national living wage |

||||||

|

|

Weekly wages |

Employers’ weekly NI contributions |

Weekly cost |

Weekly wages |

Employers’ weekly NI contributions |

Weekly cost |

Weekly |

Monthly (4.5-week month) |

Three months |

|

2016-17 |

302.63 (6.87/hr) |

15.74 |

318.37 |

322.76 (7.20/hr) |

18.22 |

340.98 |

22.61 |

101.75 |

305.24 |

|

2017-18 |

310.25 (7.04/hr) |

16.68 |

326.93 |

346.52 (7.73/hr) |

21.14 |

367.66 |

40.73 |

183.29 |

549.86 |

|

2018-19 |

317.88 (7.21/hr) |

17.61 |

335.49 |

370.73 (8.27/hr) |

24.12 |

394.85 |

59.36 |

267.12 |

801.36 |

|

2019-20 |

325.63 (7.39/hr) |

18.57 |

344.2 |

394.93 (8.81/hr) |

27.1 |

422.03 |

77.83 |

350.24 |

1050.71 |

|

2020-21 |

333.70 (7.57/hr) |

19.56 |

353.26 |

419.14 (9.35/hr) |

30.08 |

449.22 |

95.96 |

431.82 |

1295.46 |

|

*Figures are based on estimated wage rate increases (2.5% y-o-y for NMW and 7% y-o-y for NLW). NMW year runs October to September. NLW year runs April to March |

|||||||||

Many growers are also wondering how to maintain the wage differentiation between staff on the NLW and those who were on higher wages.

On top of this, auto-enrolment pensions are starting to kick in and many producers say they are having to employ a dedicated person to administer the scheme, as every worker, including seasonal, must be enrolled after three months.

Businesses with an annual labour bill in excess of £3m will also have to stump up cash for the apprentice levy when it is introduced next year. With higher labour costs, more businesses will be pushed into this bracket.

Generational change

“This is a once-in-a-generation change,” says Ali Capper, Worcestershire apple and hops grower and new chair of the NFU’s horticulture and potato board.

Before 2013, 70% of seasonal workers in the sector were aged under 25, she says. Today, 70% are aged over 25.

“I’ve had MPs and ministers from [the Department for Business Innovation and Skills] say [to me] ‘why can’t you just recruit younger people?’ But you can’t discriminate in advertising or recruitment practices. [The fact they don’t know that] is very concerning.

“The government introduced the national living wage to improve standards of living. No farmer has any problem with that, but if the cost of labour goes up, business will have to mechanise more,” she says.

“In our sector we don’t have machines ready and waiting, Nobody in the industry is thinking that commercial robotic picking is less than 10 years away, so there is no quick fix.”

Fair prices from retailers

With a prolonged price war gripping the grocery market, many growers say supermarkets will not pay for the additional cost of production they now face.

Some retailers are even coming to growers and asking for a price decrease to help them cope with the uplift in wages in their own businesses, says Ms Capper.

“We have to stand firm and say that our costs are increasing and we want this to be reflected in the prices paid,” she says.

There is also concern about how committed retailers will be to British produce when goods from other countries become so much cheaper in comparison.

“I worry that none of them will put their heads above the parapet and say that they will pay more for British,” says an anonymous grower who supplies major UK retailers.

Sector shrinkage

Speaking at the NFU conference in February, Jeremy Best, a strawberry grower from Cornwall, said “I don’t think anyone realises the consequences of this.”

His workforce of 30 will reduce by six people this year alone and some of the biggest growers in the country are also considering cutting their staff and shrinking their planting area (see Henry Chinn case study).

Allan Wilkinson, head of agriculture at HSBC, has warned that 60% of jobs could be lost in horticulture, food manufacturing and food service. Horticulture alone contributes £3bn a year to UK GDP.

The NFU has warned the NLW will lead to an increasing reliance on imported fruit and vegetables in the UK as British growers shrink their planting areas and face stiffer competition from abroad.

Farming unions are now lobbying for changes to ease the strain, including no requirement for employers to pay National Insurance for seasonal workers, or enrol them in the new pension scheme. It is also pushing for the introduction of a student seasonal worker scheme to encourage younger workers.

Guy Poskitt, Yorkshire, Lancashire and Scotland

“No labour equals no horticulture,” says Guy Poskitt, who employs 250 full-time staff and 80 seasonal workers across his enterprise.

Guy Poskitt © Jim Varney

His workers are essential to the production of the business’ 50,000t of carrots a year, as well as other root vegetables, combinable crops, pumpkins and squash.

But Mr Poskitt says he faces a £250,000 uplift in wages in the first year of the NLW alone, plus further costs as he tries to maintain differentiation between pay bands.

On top of this, pension auto-enrolment contributions and admin fees will run into the tens of thousands of pounds a year, and from April 2017, the Poskitts will have a £25,000 /year bill from the government’s new apprentice levy.

“In response we are looking at more innovation, more automation and an overtime ban, which means employing more people for less hours,” he says.

Most of this kit will come from Germany and so will not only displace British jobs, but see the investment going abroad, says Mr Poskitt. As a packer of carrots, he is also considering upping his imports.

“An increase [in the minimum wage] is needed – most people would struggle to live on this,” he concedes, but the lack of consultation around the changes remains a matter of concern.

The sector now needs help from government to invest in automation, says Mr Poskitt, and for an exclusion on national insurance payments for seasonal workers.

Case study: Henry Chinn, Herefordshire

The NLW comes into effect just as Henry Chinn and his family are entering the peak of their asparagus season, when they employ 1,000 seasonal workers in addition to their 30 permanent staff.

Henry Chinn

The Chinn family operates Cobrey Farms across more than 1,000ha in Herefordshire, Suffolk and Norfolk, growing and packing 600ha of asparagus under their well-known brand Wye Valley Asparagus, as well as forced rhubarb, blueberries, wine grapes, potatoes and combinable crops.

Asparagus, rhubarb and blueberry production are intensive processes and the business’ labour bill accounts for 65-70% of the cost of production.

Most of Cobrey Farms’ seasonal workers have been on minimum-wage contracts, so the introduction of the living wage will increase the business’ labour bill by 7% in the first year for those aged 25 and over.

Higher still

But Mr Chinn says about 50 seasonal staff are usually on wages above the minimum wage as supervisors, drivers and other roles with responsibility, so the business will have to maintain a differentiation.

The cumulative impact of a 7% year-on-year rise is the real concern, he says.

“We can take a bit of it on the chin in the first year, but not year after year, especially with increases in national insurance contributions, auto-enrol pensions and next year we will have to pay the apprentice levy.”

Pension auto-enrolment is already adding significant cost. Even though there is a three-month deferral period, which the business can sometimes use for shorter-stay seasonal workers, an extra half a person is still needed to administer the scheme and not many workers have opted out.

Retailer support needed

“We can work on production and mechanisation where possible [to make efficiencies], but we’ve been doing that for 20 years anyway.”

The family supplies virtually all of the UK’s major retailers, but Mr Chinn says he will not be receiving a higher price for his produce this year.

“The retailers are in the middle of a price war and they have very little interest in our wage costs. Long-term we have to keep finding efficiencies but ultimately we either get some price inflation or have to stop producing.”

Crops such as asparagus are long-term investments and Mr Chinn says the business has already planted asparagus with a production life of 10 years. Yet he fears that if retailers don’t pay more next year, the business will have to start shrinking its planted area.

“Given the long-term nature of the crop, we can’t just drop it. But the [increased cost] is bound to impact on what we can invest.”

Longer term, the business is also trying to grapple with the uncertainty of a possible exit from the EU.

“Access to a cost-effective and efficient workforce is absolutely critical. Brexit is a whole big question mark and I don’t think the 7% wage increase will make a difference [to attracting British workers].”

“UK produce has enjoyed fantastic support from retailers and consumers in the past 10 years or so, particularly horticulture, but if we’re not careful the living wage could derail it all.”

The challenge to Scotland

Scottish horticulture faces an even bigger challenge – the introduction of the national living wage (NLW) rate for all workers aged 16 and over.

Growers fear this will immediately put them at a disadvantage to their peers south of the border and even more so to competitors elsewhere in Europe.

“Growers are innovative, but labour is still a big factor,” says NFUS chief executive Scott Walker, who describes the current retailer environment as “cut throat”.

For Scotland’s soft fruit producers in particular there is currently no way to move to mechanisation.

Growers have been innovative in other ways and have extended the growing season by using polytunnels and growing on tables to improve picker efficiencies, but it is still a labour-intensive process, says Mr Walker.

“[The living wage] will really impact on innovation and we have some of the best-quality producers here,” he says.

“I am 100% convinced that you will always have a group of consumers who are willing to pay more for British or local produce, but they will not be able to support the whole industry, while there are others who want local but can’t afford it.

“We’re living in an uncertain world and we’re lucky in the UK, but we absolutely take food for granted.”

NFUS is consulting with Scotland’s agricultural wages board on whether to reintroduce age bands like in England and Wales, but a decision is unlikely to be reached and implemented until October.

Case study: Tracy McCulloch, East Lothian

Tracy McCulloch is the fourth generation of her family to run her farm business, W&R Logan near Haddington to the east of Edinburgh. She fears that the increased cost of the living wage will limit her ability to reinvest and remain competitive.

Tracy McCulloch

The business grows 180ha of Brussels sprouts and 155ha of cabbages, plus potatoes and parsnips, while its sister company, East Lothian Producers, acts as a packer. The family supply either directly or indirectly all the major UK retailers and export to Holland.

Overall, the businesses employ 20-100 workers depending on season with about a 50/50 split between those aged below and over 25.

Under Scottish plans, all of these workers will be paid the living wage, while in England only those aged 25 and over will be eligible.

Big hit

She estimates the business faces a £100,000-£150,000 increase in labour costs in year one alone, once the living wage, national insurance, holiday pay and wage rises up the pay band are taken into account.

All of the permanent staff, managers and tractor drivers are paid well above the minimum wage, but the changes mean 70-80% of staff will receive a pay increase.

“We have to keep that differential between skilled and unskilled workers,” says Ms McCulloch. “But a 7% rise for all is probably not manageable.

“It’s a significant increase and would impact on how much we are able to reinvest year on year and, depending on the impact of the SAWB, it could also considerably affect how competitive we can be compared to other growers and suppliers in the UK.”

Few options

Although the business will look hard at possible efficiencies, Ms McCulloch says she cannot see how they can automate more than they have already, given the machinery on the market.

“What we get for our products now has gone down in relation to the cost of production,” she says.

“It’s a high-risk industry to be in – things can happen that are completely out of your control. The years when we make money are being eroded away.

“Nobody thinks workers shouldn’t get [high wages] but it’s about how we implement it in our business.”

Ms McCulloch hopes negotiations with retail customers will reflect the increased cost and consumers will be more concerned about value for money than the lowest price.